Peter Fossett facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Peter Fossett

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | June 6, 1815 |

| Died | 1901 (aged 85–86) |

| Spouse(s) | Sarah M. Fossett |

| Parent(s) | Edith Hern Fossett Joseph Fossett |

| Relatives | Mary Hemings (grandmother) Betty Hemings (great grandmother), Hemings family |

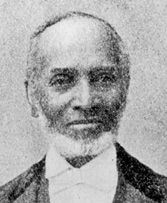

Peter Fossett (born June 6, 1815 – died January 1901) was an enslaved person at Monticello. This was the plantation owned by Thomas Jefferson. After Peter became free in the mid-1800s, he moved to Cincinnati. There, he became a minister and a caterer.

During the American Civil War, he was a captain in the Black Brigade of Cincinnati. Fossett also worked hard to improve education and prisons. He was a "conductor" on the Underground Railroad, helping enslaved people escape to freedom. In 1898, he published a book about his life called Once the slave of Thomas Jefferson.

His wife, Sarah M. Fossett, was also very active in her church and the Underground Railroad. She was a skilled hairdresser for important women in Cincinnati. She was brought to Cincinnati by Abraham Evan Gwynne. In 1860, she sued a streetcar company because she was not allowed to ride. This led to African-American women being able to ride streetcars in the city. For 25 years, she managed the Colored Orphans Asylum in Cincinnati.

Contents

Peter Fossett's Early Life

Peter Farley Fossett was born into slavery at Monticello. This was near Charlottesville, Virginia, on June 6, 1815. His parents were Edith Hern Fossett and Joseph Fossett. Edith was the main cook at Monticello. Joseph was a blacksmith. Most enslaved people at Monticello did not get paid. However, Joseph managed the blacksmith shop. He received a part of the shop's earnings.

Unlike many enslaved people who worked in the fields, Peter learned to read and write. His work was also less physically demanding. He helped his parents and worked as a house servant. Sometimes, he received tips for his work. According to Fossett, Jefferson allowed enslaved children to be educated with his grandchildren. Lewis Randolph, Jefferson's grandson, was Peter's teacher.

His grandmother was Mary Hemings Bell. She lived in Charlottesville. She gave him nicer clothes than other enslaved people at Monticello. He was the great-grandson of Betty Hemings.

...we did not need to know that we were slaves. As a boy I was not only brought up differently, but dressed unlike the plantation boys. My grandmother was free, and I remember the first suit she gave me. It was of blue nankeen cloth, red morocco hat and red morocco shoes. To complete this unique costume, my father added a silver watch.

—Peter Fossett, quoted in New York World, January 30, 1898

Life as an Enslaved Person

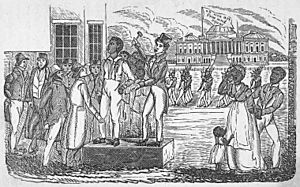

Peter Fossett was enslaved at Monticello. After Jefferson died, an auction was held in January 1827. The enslaved people of Monticello were sold. Peter, seven of his brothers and sisters, and his mother were put up for sale. His father was one of five people Jefferson had freed in his will.

Born and reared as free, not knowing that I was a slave, then suddenly, at the death of Jefferson, put upon an auction block and sold to strangers.

—Peter Fossett

Eleven-year-old Peter felt like he was being sold like an animal. He was bought by Colonel John Jones. Jones ran his plantation differently from Jefferson. At Monticello, Peter had learned to read and write. Jones threatened him with whippings if he continued. Peter still secretly read, wrote, and taught other enslaved people. One time, Jones caught Fossett reading a book. He threw the book into the fire. He said, "If I ever catch you with a book in your hands, thirty-and-nine lashes on your bare back."

Peter's father gave him a copy book so he could write. Fossett later created fake papers for people escaping slavery. These papers made it look like they were free.

Jones was harsh to Fossett. However, Jones's wife treated him like a family member. Mrs. Jones welcomed preachers of any faith who traveled through the area. These preachers made a big impression on Fossett. Jones himself also began to care for Fossett.

Peter ran away from Jones's plantation twice. Both times, he was caught. He felt like he would either become a free man or die trying. The second escape led to Fossett being put in jail. Then, he was sold at an auction again.

Peter's father, Joseph, moved to Ohio around 1840. He moved to Cincinnati around 1843. Joseph made trips back to Virginia to see his family. He worked to buy his family out of slavery. But Peter's owner, John Jones, would not sell him until his second escape. Peter was put on the auction block in 1850. At 35 years old, he was bought and freed. This was thanks to his father, family, and friends of Jefferson.

Career and Community Work

After he became free, Peter moved to Cincinnati, Ohio, to be with his family. When he first arrived, he worked several jobs. He was a waiter for a caterer and also a whitewasher. He later became a caterer, working with his brother William. In the 1870s, he opened his own catering business. His customers were among the most important people in Cincinnati. The Ohio History Center says he was likely very good at French cooking. His mother had learned a lot about this type of cooking while enslaved at Monticello.

Peter was a "conductor" on the Underground Railroad. He helped Levi Coffin, who was known as the "president of the Underground Railroad." Coffin praised Fossett for his "zealous efforts" to help people escape to freedom. Ohio was not a slave state. However, the Underground Railroad often led people to Canada for safety. Some stayed in African-American communities in Ohio. Conductors risked their lives by bringing people escaping slavery into their homes. They helped them get to the next safe place on the railroad. John Parker helped people cross the Ohio River by boat.

Fossett also worked to improve prisons. He was on the school system's board of directors. At that time, the school system was segregated.

When he arrived in Cincinnati, Fossett joined the Union Baptist Church. He became a trustee and clerk there. In 1870, he became a minister. He started his own church, and Fossett paid for much of its construction. He was the pastor of that church for 25 years. It later became the First Baptist Church in Cumminsville, Ohio. He was a pastor for 32 years in total. He ministered to African-American people across the country.

He is held in great regard by colored people and is loved by all the white ministers of Cincinnati, who know him well and esteem him highly.

—New York World, January 30, 1898

He wrote his life story in the book Once the slave of Thomas Jefferson in 1898.

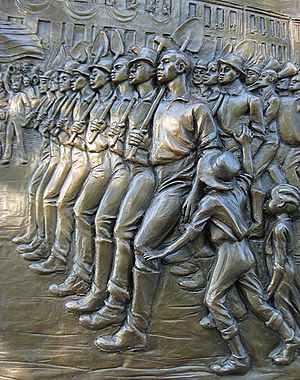

Military Service

Captain Peter Fossett served with a unit of African Americans. This unit was called the Black Brigade of Cincinnati. They built defenses for the city along the Ohio River during the American Civil War (1861–1865).

Marriage and Family

Fossett married Sarah Mayrant. She was born in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1826. Her parents were Judith and Rufus Morant (or Mayrant). Abraham Evan Gwynne, the father of Alice Claypoole Vanderbilt, brought Sarah to Cincinnati. There, she met wealthy and important people in Cincinnati society. As a young girl, she learned how to style hair from a French expert in New Orleans. When she came to Cincinnati, she became a hairdresser for wealthy white women. "Through their influence she secured entry in its exclusive group and had no superior in her profession," as quoted in The History of Black Business in America.

Sarah arrived in Cincinnati by 1854. That year, she married Peter Fossett. Like her husband, she was active in the community. This included the First Baptist Church of Cumminsville and orphanages in Cincinnati. She also helped enslaved people on the Underground Railroad. She managed the Colored Orphan Asylum for more than 25 years. The Fossetts lived in a "comfortable, well furnished and well provided home" in Cincinnati. They had four children, but only one lived to adulthood. Their married daughter's name was Martha "Mattie" E. Kelly.

In 1860, Sarah protested when she was not allowed to board a streetcar. Her efforts led to African-American women being allowed to ride Cincinnati's streetcars. When a white conductor stopped her from riding, she sued the streetcar company and won. It took several more years before African-American men were allowed to ride the city's streetcars. Sarah Fossett died in December 1906.

Later Life and Death

In 1900, Peter Fossett believed he did not have much longer to live. With the help of friends, he traveled to Monticello. He was allowed to stay there as long as he wished. Fossett had said that Monticello seemed like an "earthly paradise" when he was a boy. After two weeks of an illness related to his age, Fossett died in early January 1901. He was thought to be the last surviving enslaved person from Monticello.

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |