Levi Coffin facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

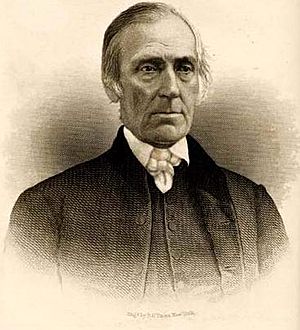

Levi Coffin

|

|

|---|---|

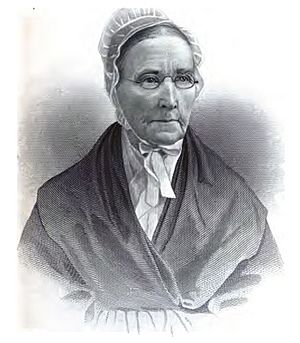

A drawing based on a circa 1850 engraving

|

|

| Born | October 28, 1798 Guilford County, North Carolina, U.S.

|

| Died | September 16, 1877 (aged 78) |

| Resting place | Spring Grove Cemetery, Cincinnati, Ohio |

| Occupation | Farmer Pork Packing Merchant Banking |

| Known for | his work with Underground Railroad |

| Political party | Whig Republican |

| Board member of | Western Freedman's Society Second State Bank of Indiana Board of Directors |

| Spouse(s) | Catherine (White) Coffin (1803–81) |

| Parent(s) | Prudence and Levi Coffin Sr. |

| Relatives | Vestal Coffin (cousin) Lucretia Coffin Mott (cousin) |

| Signature | |

Levi Coffin (October 28, 1798 – September 16, 1877) was an important American Quaker and abolitionist. An abolitionist was someone who worked to end slavery. He was also a farmer and businessman.

Levi Coffin was a key leader of the Underground Railroad in Indiana and Ohio. The Underground Railroad was a secret network that helped enslaved people escape to freedom. Some people called Coffin the "President of the Underground Railroad." They believed he helped about 3,000 enslaved people escape. His home in Fountain City, Indiana, is now a museum. It is sometimes called the Underground Railroad's "Grand Central Station."

Coffin was born in North Carolina, where he saw slavery firsthand. His family moved to Indiana in 1826. They were Quakers, and their faith did not allow them to own slaves. Quakers often helped enslaved people escape. In Indiana, Coffin became a successful merchant and business leader. His money and standing in the community helped him provide food, clothing, and transportation for the Underground Railroad.

In 1847, Coffin moved to Cincinnati, Ohio. There, he ran a warehouse that sold only goods made by free workers. This business was not very profitable, and he closed it after ten years. However, during this time, he continued to help hundreds of runaway slaves. He often hid them in his Ohio home. This home was across the Ohio River from Kentucky, which was a slave state.

In his later years, Coffin traveled to France and Great Britain. He helped create groups to provide food, clothing, money, and education for former slaves. He retired in the 1870s and wrote his autobiography, Reminiscences of Levi Coffin. It was published in 1876, a year before he died.

Contents

Early Life and His Fight Against Slavery

Levi Coffin was born on a farm in Guilford County, North Carolina, on October 28, 1798. He was the only son of Prudence and Levi Coffin Sr. He had six sisters. His parents were devoted Quakers. They attended the historic New Garden Friends Meeting. Coffin's family had never owned slaves.

In his autobiography, Reminiscences of Levi Coffin, he wrote that he learned his anti-slavery views from his family. The teachings of John Woolman, who believed slavery was wrong, influenced them. When Coffin was seven, he saw an enslaved man in chains. The man said he was bound to stop him from escaping to his family. This event deeply affected Coffin.

By age fifteen, Coffin was helping his family assist escaping slaves. They brought food to people hiding on their farm. As laws against helping slaves became stricter, the Coffins worked in secret, mostly at night. In 1821, Coffin and his cousin, Vestal, started a Sunday School. They taught enslaved people to read the Bible. But slaveholders soon forced the school to close.

Many Quakers left North Carolina because of the harsh laws and persecution. They moved to the Northwest Territory, where slavery was forbidden. In 1822, Coffin visited Indiana. He saw how well Quakers were doing there. He decided that Quakers and slaveholders could not live together. So, he chose to move to Indiana.

Marriage and Family Life

On October 28, 1824, Levi Coffin married his friend, Catherine White. They were married at the Hopewell Friends Meetinghouse in North Carolina. Catherine's family also helped enslaved people escape. This is likely how she and Levi met.

The couple planned to move to Indiana. But they waited after Catherine became pregnant with their first child, Jesse, born in 1825. Levi's parents moved to Indiana in 1825. Levi, Catherine, and their baby followed them later that year. In 1826, they settled in Newport, which is now Fountain City, Indiana.

Catherine was just as active as Levi in helping runaway slaves. She provided them with food, clothing, and a safe place to stay in their home. Levi said about his wife, "Her sympathy for those in distress never tired." Catherine White became known as "Aunt Katie" to the enslaved people on the run.

Levi Coffin's Work

Helping Slaves in Indiana

After moving to Indiana, Coffin continued farming. Within a year, he opened the first dry-goods store in Newport. He later said that his successful business helped him afford the expensive work of the Underground Railroad. This network provided safe places for enslaved people traveling north to Canada.

The Underground Railroad was active in Indiana by the early 1820s. Coffin's home in Newport quickly became a stop on this secret route. Many free Black people lived near Newport. Runaway slaves often hid there, but slave catchers knew these spots. Coffin contacted the local Black community. He let them know he would hide runaways in his home for better safety.

Coffin started sheltering runaway slaves in his Indiana home in the winter of 1826–27. News of his actions spread. Many neighbors, who had been afraid to help, joined him after seeing his success. They created a more organized way to move fugitives from one safe house to the next. Coffin called it the "mysterious road." The number of escaping slaves grew. Coffin estimated he helped about one hundred people escape each year.

The Coffin home became a meeting point for three main escape routes. These routes came from Madison, Indiana, New Albany, Indiana, and Cincinnati, Ohio. Sometimes, two wagons were needed to transport the large groups of runaways further north. Coffin moved the escaping slaves to the next stops at night. He had many helpers, like George DeBaptiste in Madison.

Slave hunters often threatened Coffin's life. His friends worried about his safety and tried to make him stop. But Coffin was guided by his strong religious beliefs. He explained:

After listening quietly to these counselors, I told them that I felt no condemnation for anything that I had ever done for the fugitive slaves. If by doing my duty and endeavoring to fulfill the injunctions of the Bible, I injured my business, then let my business go. As to my safety, my life was in the hands of my Divine Master, and I felt that I had his approval. I had no fear of the danger that seemed to threaten my life or my business. If I was faithful to duty, and honest and industrious, I felt that I would be preserved, and that I could make enough to support my family.

Some neighbors who opposed his work boycotted his store. But as more people moved to the area, many supported the anti-slavery movement. Coffin's business then grew. He invested in the Second State Bank of Indiana and became a director. He also expanded his business to include a mill and a hog-butchering operation. He even bought 250 acres (100 hectares) of land.

In 1838, Coffin built a two-story brick home in Newport. This home, now called the Levi Coffin House, became known as the "Grand Central Station" of the Underground Railroad. It had secret hiding places for runaway slaves. A hidden door in the maids' quarters led to a narrow space between the walls. Fourteen people could hide there. When slave hunters came, Coffin would demand to see search warrants. By the time they returned with papers, the slaves would be gone. His home was never searched.

In the 1840s, Quaker leaders advised members to stop helping runaway slaves. They believed legal changes were the best way to end slavery. But Coffin continued his work. In 1843, the Quaker society expelled him. Coffin and other Quakers who supported him formed the Antislavery Friends. They reunited with the main Quaker group in 1851.

Despite the opposition, the Coffin family's desire to help grew stronger. Catherine Coffin organized a sewing group at their home. They made clothes for the runaways. She also provided meals and shelter. Other aid came from sympathetic neighbors. Coffin realized many goods he sold were made by slave labor. He started buying from organizations that used only free labor. These "free-labor goods" were not very profitable for him.

People in the eastern United States wanted a similar free-labor organization in the west. They asked Coffin to manage the Western Free Produce Association. At first, he said no. He lacked money and did not want to move to a city. But in 1845, abolitionist businessmen opened a warehouse in Cincinnati. The Free Produce Association raised $3,000 to stock it. They kept pressuring Coffin to lead it. He finally agreed to oversee the warehouse for five years. In 1847, Levi and Catherine Coffin moved to Ohio.

Life and Work in Cincinnati

In 1847, Coffin moved to the Cincinnati area to manage the wholesale warehouse of free-labor goods. He planned to return to Indiana after five years. He rented out his Newport business and arranged for his Indiana home to remain an Underground Railroad stop. In Cincinnati, he worked to get a steady supply of free-labor goods. The main problem was the poor quality of these goods. It was hard to find free-labor cotton, sugar, and spices that were as good as those made by slave labor. This made it difficult to sell the products, and the business struggled financially.

To get good-quality free-labor products, Coffin traveled south. He looked for plantations that did not use slave labor. He found a cotton plantation in Mississippi where the owner had freed all his slaves and hired them. The plantation struggled because it had no equipment. Coffin helped the owner buy a cotton gin, which greatly increased production. This provided a steady supply of cotton for Coffin's business. The cotton was sent to Cincinnati, spun into cloth, and sold. Other trips to Tennessee and Virginia were less successful.

Despite Coffin's hard work, the poor supply of free-labor products was a big problem. He could not find someone to take over the company so he could return to Indiana. The business stayed open mainly because wealthy supporters helped financially. Coffin sold the business in 1857, realizing it could not be profitable.

Cincinnati already had a strong anti-slavery movement. Coffin bought a new home and continued his work with the Underground Railroad. He set up a new safe house and helped organize a larger network in the area. He was careful at first, waiting to find local people he could trust.

The Coffins moved several times in Cincinnati. They finally settled on Wehrman Street. Their large home had rooms rented out for boarding. Many guests came and went, making it a perfect place for an Underground Railroad stop without causing suspicion. When runaways arrived, they were dressed as servants or other workers. Catherine made uniforms for them. Some mixed-race individuals could pass as white guests. The most common disguise was a Quaker woman's outfit. Its high collar, long sleeves, gloves, veil, and wide-brimmed hat could hide the wearer's face.

One famous story of an escaped slave was in Harriet Beecher Stowe's book, Uncle Tom's Cabin. It tells of Eliza Harris, who escaped by crossing the Ohio River in winter. Barefoot and carrying her baby, Eliza found safety. A fictional Quaker couple, Simeon and Rachael Halliday, gave her food, clothes, shoes, and shelter. Eliza then continued to freedom in Canada. Stowe lived in Cincinnati at the time. She knew the Coffins, who may have inspired the Halliday couple in her novel.

As the American Civil War neared, Coffin's role changed. In 1854, he visited a community of escaped slaves in Canada to offer help. He also helped start an orphanage for Black children in Cincinnati. When the war began in 1861, Coffin and his group prepared to help the wounded. As a Quaker, he was against war, but he supported the Union. Coffin and his wife spent almost every day at Cincinnati's military hospital. They cared for the wounded, gave out coffee, and took many soldiers into their home.

In 1863, Coffin became an agent for the Western Freedman's Aid Society. This group helped slaves freed during the war. As Union troops moved south, Coffin's group sent aid to slaves who escaped to Union areas. They collected food and other goods for former slaves behind Union lines. Coffin also asked the U.S. government to create the Freedmen's Bureau to help freed slaves. After the war, he helped former slaves start businesses and get an education. In 1864, he went to Great Britain to seek aid. His efforts led to the formation of the Englishman's Freedmen's Aid Society.

Later Years and Legacy

After the war, Coffin raised over $1,000 in one year for the Western Freedman's Aid Society. This money provided food, clothing, and other aid to the newly freed slave population. In 1867, he was a delegate at the International Anti-Slavery Conference in Paris.

Coffin did not enjoy being in the public eye. He felt that asking for money was demeaning. He wrote in his autobiography that he was happy to leave that job once a new leader was chosen. Coffin believed that giving money freely to all Black people might not help them in the long run. He thought that education and farms were needed. He also felt the Society should focus its limited resources on those who could benefit most. The Society operated until 1870, the year Black men gained the right to vote under the Fifteenth Amendment.

Coffin spent his final years retired from public life. He wrote about his experiences with the Underground Railroad. In his autobiography, Coffin wrote, "I resign my office and declare the operations of the Underground Railroad at an end." Historians consider Reminiscences of Levi Coffin, published in 1876, one of the best firsthand accounts of the Underground Railroad.

Death and Remembering Levi Coffin

Levi Coffin died on September 16, 1877, at his home in Avondale, Ohio. His funeral was held at the Friends Meeting House of Cincinnati. The Cincinnati Daily Gazette reported that hundreds of people had to stay outside because the crowd was too large. Four of Coffin's eight pallbearers were free Black men who had worked with him on the Underground Railroad. Coffin was buried in an unmarked grave at Cincinnati's Spring Grove Cemetery. His wife, Catherine, who died four years later in 1881, is also buried there.

Coffin was known for his bravery in helping runaway slaves. He inspired his neighbors to help, even though many were afraid to hide people in their homes. He was first called the unofficial "President of the Underground Railroad" by a slave catcher. The slave catcher said, "There's an underground railroad going on here, and Levi's the president of it." This informal title became common among other abolitionists and former slaves.

Historians believe the Coffins helped about 2,000 enslaved people escape during their twenty years in Indiana. They helped an estimated 1,300 more after moving to Cincinnati. Coffin himself estimated the total number to be around 3,000. When asked why he helped, Coffin once replied: "The Bible, in bidding us to feed the hungry and clothe the naked, said nothing about color, and I should try to follow out the teachings of that good book."

On July 11, 1902, African Americans placed a 6-foot (1.8 m) tall monument at Coffin's previously unmarked grave in Cincinnati.

The Levi Coffin House in Fountain City, Indiana, was named a National Historic Landmark in 1966. It was also added to the National Register of Historic Places. Indiana's state government bought the Coffin home in 1967 and restored it. The home opened to the public as a historic site in 1970.

See also

- Peter Fossett, a former enslaved person who helped with Coffin's Underground Railroad

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |