Phonautograph facts for kids

The phonautograph was the very first machine known to record sound. Before this invention, people could only trace the movements of vibrating objects like tuning forks. But they couldn't record actual sound waves traveling through the air.

A French inventor named Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville created the phonautograph. He received a patent for it on March 25, 1857. This device drew sound waves as wiggly lines on paper or glass coated with smoke. Scott thought that one day, people would be able to "read" these tracings like a special kind of writing.

The phonautograph was made for science labs. Scientists used it to study acoustics, which is the science of sound. They could see and measure how loud sounds were and what their shapes looked like. They could also figure out the frequency (how high or low) of a musical pitch.

For a long time, no one realized that these recordings, called phonautograms, held enough information to play the sounds back. The tracings were just thin lines, so you couldn't play them directly. However, in 2008, scientists found some phonautograms from before 1861. They scanned them with computers and turned them into digital audio files. This allowed them to hear the sounds for the first time!

Contents

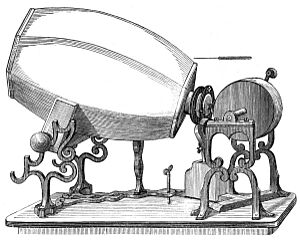

How the Phonautograph Was Built

Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville patented his phonautograph on March 25, 1857. He worked as an editor in Paris, helping to publish scientific books. One day, he saw a drawing of the human ear in a book. This gave him the idea to "photograph the word."

Around 1853 or 1854, Scott started working on a machine that could "write speech itself." He wanted to build something that worked like a human ear.

Here's how it worked:

- Scott covered a glass plate with a thin layer of soot (lampblack).

- He used a special trumpet. At the narrow end, he attached a thin membrane, like an eardrum.

- In the middle of this membrane, he put a stiff boar's bristle (a tiny needle). This bristle just barely touched the soot.

- Someone would speak into the trumpet. The sound made the membrane vibrate, and the bristle scratched lines into the soot.

- The glass plate slid along at a speed of one meter per second while the sound was being recorded.

On March 25, 1857, Scott received the French patent for his device. He called it the phonautograph.

First Recorded Sounds

The first known clear recording of a human voice happened on April 9, 1860. Scott recorded someone singing the song "Au Clair de la Lune" ("By the Light of the Moon").

Scott's machine was not made to play sounds back. He wanted people to read the tracings, which he called phonautograms. Other scientists had used devices to trace vibrations before. For example, English physicist Thomas Young used tuning forks this way in 1807.

By late 1857, Scott's phonautograph was precise enough for scientists to use. It helped create the new science of acoustics.

Rediscovering the Phonautograph

The true importance of the phonautograph wasn't fully understood until March 2008. That's when a group called First Sounds found it in a Paris patent office. This group included American audio historians and engineers. They wanted to share the earliest sound recordings with everyone.

Scientists at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California then turned the phonautograms into digital sound. They were able to play back the recorded sounds! Scott himself had never imagined this was possible.

Before this discovery, people thought the oldest human voice recording was from 1877. That was a phonograph recording made by Thomas Edison. The phonautograph also helped develop the gramophone. Its inventor, Emile Berliner, worked with the phonautograph while creating his own device.

How Phonautograms Were Played Back

By April 1877, a man named Charles Cros realized something important. He figured out that a phonautograph recording could be turned back into sound. He thought you could engrave the tracing onto a metal surface. This would create a groove that could be played. Then, a needle and a special part (a diaphragm) could be used to recreate the sound.

But before Cros could try his idea, Thomas Edison announced his phonograph. Edison's machine recorded sound by pressing it into a sheet of tinfoil. This sound could be played back right away. Because of this, Cros's idea was forgotten for a while.

Berliner's Experiments

Ten years later, Emile Berliner experimented with recording. He created the disc Gramophone. His early recording machine was like a disc version of the phonautograph. It drew a clear spiral line through a thin black coating on a glass disc.

Berliner then used Cros's idea of engraving. He made a metal disc with a playable groove. You could say that Berliner's experiments around 1887 were the first time sounds were played back from phonautograph recordings.

However, no one tried to play any of Scott de Martinville's original phonautograms using this method. Maybe the images of them that were available were too short or unclear to encourage such an experiment.

Modern Playback

Almost 150 years after they were made, some good phonautograms were found. They were stored with Scott de Martinville's papers in France's patent office. High-quality images of these recordings were taken.

In 2008, the First Sounds team played back the recordings as sound for the first time. They used modern computer programs to do this. At first, they used a special system for playing recordings that were too old or damaged for normal players. Later, they found that regular image-editing and sound conversion software worked too. All they needed was a good scan of the phonautogram and a computer.

For the March 2008 release of "Au Clair de la Lune," engineers wrote software to make the sound clearer. They did the same for a May 17, 1860, recording called "Gamme de la Voix."

Sounds That Were Found

One phonautogram, made on April 9, 1860, turned out to be a 20-second recording of the French folk song "Au clair de la lune". At first, it was played at double speed. People thought it was the voice of a woman or child.

But then, more recordings were found with notes from Scott de Martinville. These notes showed that he was the one speaking. When played at the correct speed, it's clearly a man's voice, almost certainly Scott de Martinville himself, singing the song very slowly.

Two other recordings from 1860 were also found. They contained "Vole, petite abeille" ("Fly, Little Bee"), a lively song from a comic opera. Before this, the oldest known recording of singing was an 1888 Edison wax cylinder recording of a Handel concert.

A phonautogram with the first lines of Torquato Tasso's play Aminta was also discovered. This recording was probably made in April or May 1860. It is the earliest known recording of clear spoken words that has been played back. It is even older than Frank Lambert's 1878 talking clock recording.

Earlier recordings from 1857, 1854, and 1853 also have Scott de Martinville's voice. But these are hard to understand because they are not very clear, are very short, and the speed changes. Only one of these, a cornet scale recording from 1857, was fixed and made clear enough to hear.

See also

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |