Pirro Ligorio facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Pirro Ligorio

|

|

|---|---|

Pirro Ligorio

|

|

| Born | c. 1512 Naples, Italy

|

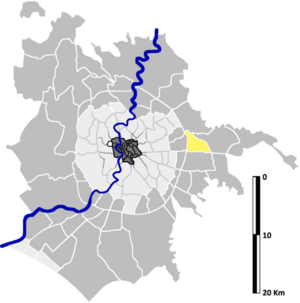

| Died | 30 October 1583 (aged about 70) Ferrara, Italy

|

| Nationality | Italian |

| Known for | Architecture, painting, garden design, antiques |

|

Notable work

|

Villa d'Este, Casina Pio IV |

| Movement | High Renaissance |

Pirro Ligorio (around 1512 – October 30, 1583) was a talented Italian artist during the Renaissance period. He was an architect, painter, expert on ancient history, and garden designer. Pirro Ligorio worked for the Vatican as the Pope's Architect. He designed the famous fountains at Villa d'Este in Tivoli. He also served as an expert on ancient artifacts in Ferrara. Ligorio loved and deeply studied ancient Roman culture.

Contents

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

Not much is known about Pirro Ligorio's early life. He was likely born in Naples, Italy, around 1512 or 1513. Naples was under Spanish rule at the time. His parents, Achille and Gismunda Ligorio, were thought to be from a noble family. Around age twenty, Ligorio moved to Rome. He wanted to find better opportunities in the city's lively art scene. The Vatican especially supported many artists.

Painting and Decoration Work

In Rome, Ligorio started by painting and decorating the outside walls of homes and palaces. This job was open because another artist, Polidoro da Caravaggio, had left. Ligorio had little formal art training. His first known job was in 1542. He decorated a loggia (an open-sided gallery) at an archbishop's palace. He was chosen for his skill in the "grotesque" style. This style used patterns, scenes from Roman history, and trophies. Ligorio loved this style and used it often.

Sadly, many of his early paintings were later destroyed or painted over. But some of his drawings from that time still exist. Historians identified them by their subjects. These drawings often showed building decorations, Roman figures, and ancient objects. These drawings are now in art collections worldwide. One is even at the Art Institute of Chicago.

Fresco Painting and Ancient Studies

In the mid-1500s, Ligorio helped decorate the Oratory of San Giovanni Battista Decollato in Rome. He painted a fresco called The Dance of Salome. He likely painted it between 1544 and 1553. This fresco shows Ligorio's use of the Raphaelesque and Mannerist styles. It is one of the few large works from his early career that still exists.

Around this time, Ligorio also began studying classical antiquity. He spent much of the 1540s learning about Roman artifacts. He saved important information when some popes destroyed artifacts during excavations. In the next ten years, he worked to share this knowledge. He published a book, Delle antichità di Roma, in 1553. He also made engravings of several ancient objects. He tried to write a huge encyclopedia about Roman and Greek history. Parts of it are now in the Biblioteca Nazionale Vittorio Emanuele III in Naples. Some people criticized Ligorio's writings. They accused him of making up some information. But no strong proof of this has ever been found.

Mapping Ancient Rome

Ligorio's work as an archaeologist also led him to create maps. Between 1557 and 1563, he used his knowledge of ancient history and his drawing skills to make several maps of Rome. His most famous map was published in 1561. It was called “Antiquae urbis imago” (Image of Ancient Rome). This map showed the layout of ancient Rome. It was considered his best work in map-making.

Working for the Vatican

Under Pope Paul IV (1555–1559)

When Pope Paul IV became Pope, he wanted an architect from Naples, like himself. In 1558, he hired Ligorio as the Architect of the Vatican Palace. Ligorio's assistant was Sallustio Peruzzi.

Ligorio's first big project was the chapel in the new Papal apartment. The Pope had moved into his new home by 1556. But the chapel was not finished. Ligorio designed two large angel paintings for it. He finished the chapel in about ten months. He also started designing a small building, a "casino," for the Pope near Belvedere Court. This project was delayed due to money issues. But it later became one of Ligorio's most important works under the next Pope.

Pope Paul IV also wanted to improve the papal palace. He wanted more light in the Hall of Constantine. Ligorio was chosen to fix this problem. They decided to remove an old apartment and add a rooftop garden. This allowed more light into the Hall of Constantine.

Near the end of Paul IV's time as Pope, he asked Ligorio to design a special container for religious items, called a monstrance. It was for papal trips and would be kept in the new chapel. Paul IV died before it was finished. But the next Pope wanted unfinished projects completed. So, Ligorio finished the monstrance, and it was sent to Milan as a gift.

Under Pope Pius IV (1559–1565)

Pope Pius IV became Pope in 1559. He was known for supporting the arts, especially architecture. In his first three years, he spent a lot of money on building projects. He liked to finish projects that were already started, rather than beginning new ones. This fit well with Ligorio's goal to restore old artifacts and preserve ancient history.

Ligorio continued to work with his assistant, Sallustio Peruzzi. Their first major project was updating the Vatican Library in 1560. They might have planned a new library, but due to lack of money, Ligorio likely did smaller updates like woodworking and stone work. He also did other small jobs, like building apartments in the palace.

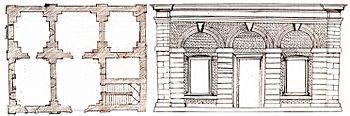

In May 1560, Ligorio got a very important job. He was to continue the Pope's plans for the papal casino. This building was in the woods behind the Belvedere court. Pius IV's new plans included a second floor, a large fountain, and an oval courtyard with arched entrances. The decorations were in Ligorio's favorite Raphaelesque style. It was named the Casino Pio IV to honor Pope Pius IV. A historian named Jacob Burckhardt called it "the most beautiful afternoon retreat that modern architecture has created."

On December 2, 1560, Ligorio was given honorary Roman citizenship. This was a huge honor. Only three other people received it in the 1500s: Michelangelo, Titian, and Fra Guglielmo della Porta. For the rest of his life, Ligorio was proud to be both a Neapolitan and a Roman citizen. This recognition also led to more projects for Ligorio. This made Pius IV's time as Pope one of Ligorio's busiest periods.

During this time, Ligorio also worked on engineering projects. Popes were responsible for protecting cities in their territory. This included repairing city defenses. As a Renaissance architect, Ligorio also handled engineering tasks. He is especially remembered for helping restore the Acqua Vergine. This was an ancient Roman aqueduct (a water channel). It was broken, forcing Romans to use dirty water from the Tiber River. Ligorio insisted it be rebuilt. The work started in April 1561 and took about five years.

In the early 1560s, the Pope wanted to finish several projects in the Belvedere Court. Ligorio focused on the Nicchione, a large niche built by Bramante. He added a semicircular loggia. This space was later used for fireworks displays during Rome's festivals. Ligorio also added an open-air theater to the southern end of the Belvedere Court. It was finished in May 1565. Sadly, this theater was torn down later. The Belvedere Court was used for a big tournament in March 1565. It celebrated the marriage of the Pope's nephew. The Nicchione was designed to be seen from a window in the Pope's apartment, like a framed painting.

In 1565, Pius IV also asked Ligorio to organize the Vatican archives (important historical records). Ligorio designed a building to hold these records. Not much of this building remains today. But its design was simpler than Ligorio's usual fancy style. His other buildings often had beautiful, detailed decorations. This archive building was plain and practical. Ligorio designed it to fit its simple purpose, as the Pope wished.

After Michelangelo died, Ligorio was appointed architect of the San Pietro church in May 1564. This made Giorgio Vasari, a fan of Michelangelo and Ligorio's rival, very upset. The second architect on the project was Giacomo Barozzi da Vignola. They made little progress on the church. They were later removed from their duties by the new Pope.

Brief Imprisonment

Ligorio's work at the Vatican was briefly stopped in the summer of 1565. He was held for one week. There were accusations that he had misused building materials during his papal projects. He was investigated, and his writings were taken away. He was released without much trouble, except that some valuable medallions were taken from him. These accusations added to Ligorio's already debated reputation.

Under Pope Pius V (1566–1572)

Pope Pius V had different ideas than his predecessor. He did not work much with Ligorio. He gave Ligorio some small woodworking and design jobs. Ligorio kept his title of Palace Architect until possibly June 1567. During his final years in this role, he actually returned to Ferrara for other work.

Work in Ferrara

Cardinal Ippolito II d'Este

In September 1550, before he worked for the Vatican, Ligorio was hired by Ippolito II d'Este, the Cardinal of Ferrara. Ligorio went with him to Tivoli. While the Cardinal was governor there, Ligorio managed his collection of ancient artifacts. He also served as a top advisor. The area had many remains of old villas and temples. This allowed Ligorio to continue his research on Roman antiques. It also helped the governor add to his own collection.

Designing Villa d'Este Gardens

In Tivoli, Ippolito II d'Este decided to turn an old monastery into his own grand villa. Building was slow for most of the next ten years due to the Cardinal's changing duties. But it fully restarted in 1560. Giovanni Alberto Galvani was the main architect. However, Pirro Ligorio was in charge of the villa's large and complex gardens. These gardens included many water features and fountains. Ligorio used his knowledge of aqueduct engineering for these. The gardens also had a collection of ancient sculptures. Ligorio designed both a larger public garden and a smaller private garden. The private garden could be reached directly from the palace. It used shaded walls to create a quiet, hidden space.

David Coffin, Ligorio's main biographer, said Ligorio used three main themes in these gardens. First, he focused on the link between nature and art. This was a key idea during the Renaissance. Many of Ligorio's water features and sculptures included plants and animals. This blended the natural parts of the garden with the man-made art. Second, there was a geographic theme. Ligorio designed the fountains to represent three rivers flowing into the Fountain of Rome. This honored the cardinal's love for the arts. Finally, Ligorio used mythological symbols. He especially showed the influence of the Garden of the Hesperides. This use of images of Hercules and his struggle between good and bad showed Ligorio's knowledge of ancient Greek and Roman myths. It also showed the cardinal's Christian faith.

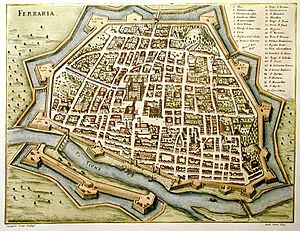

Working for Duke Alfonso II d'Este

Much later, after his work for the Vatican, Ligorio returned to Ferrara. This time, he had a more academic role. Starting in December 1568, he worked for Duke Alfonso II d'Este of Ferrara. He was the Ducal Antiquarian, an expert on ancient things. He also became a Lector (teacher) at the University of Ferrara. Ligorio's main jobs were to prepare the duke's library. He also organized an antique museum for Alfonso's court. He added many drawings and designs to these records. He continued to be known for his knowledge of ancient history in Ferrara. In 1580, he was named an honorary citizen of Ferrara. This added a third part to his identity, along with being Neapolitan and Roman.

On November 16, 1570, a major earthquake hit Ferrara. It caused a lot of damage to buildings. This made Ligorio very interested in earthquakes. He decided to write a book about historical earthquakes. He wrote about the effects of the Ferrara earthquake for several months. Then he started making plans for an earthquake-resistant home. Ligorio thought of earthquakes as natural events, not supernatural ones. He believed people could design buildings to withstand them. Many of his ideas, like thicker brick walls and stone supports, are similar to modern earthquake-resistant building methods. This shows Ligorio's focus on both the design and the strong structure of his buildings.

Legacy and Impact

Pirro Ligorio reportedly died in October 1583. He had a bad fall in Ferrara.

Even though he made big contributions to Renaissance Italian architecture, ancient history, and garden design, Pirro Ligorio is not as well-known as some other artists of his time. The first biography of Ligorio was published in 1642 by Giovanni Baglioni. Later biographies repeated it, but with many mistakes. This might be because there isn't much information about Ligorio's life. For example, almost nothing is known about his first thirty years. Also, many of Ligorio's designs, drawings, and buildings were destroyed over time. This makes it harder to document his work. In the 1900s, a historian named David Coffin wrote his main study on Ligorio's life. Coffin became the world's top expert on the architect. Coffin's book, Pirro Ligorio: The Renaissance Artist, Architect, and Antiquarian, is still the most important and complete record of Ligorio's life and work.

In his book, Coffin describes Ligorio's personality. He had three main traits: curiosity, imagination, and ambition. His curiosity led him to work on many different projects. These included painting, garden design, engineering, map-making, and archaeology. His imagination can be seen in the amazing way he combined plants, sculptures, water features, and myths in the gardens at Tivoli. Finally, his ambition meant he worked with great focus and passion. He gained both admirers and rivals. One rival was fellow Renaissance architect Giorgio Vasari. Vasari refused to include a biography of Ligorio in his famous book, Vite. This greatly affected how Ligorio's legacy was remembered. It meant his life was much less documented compared to other artists of his time.

See also

In Spanish: Pirro Ligorio para niños

In Spanish: Pirro Ligorio para niños

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |