Plan 9 from Bell Labs facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Plan 9 from Bell Labs |

|

|---|---|

Glenda, the Plan 9 mascot in a space suit, drawn by Renée French

|

|

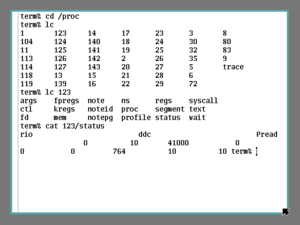

rio, default user interface of Plan 9 from Bell Labs

|

|

| Developer | Plan 9 Foundation, succeeding Bell Labs |

| Written in | Dialect of ANSI C |

| Working state | Current |

| Source model | Open source |

| Initial release | 1992 (universities) / 1995 (general public) |

| Final release | Fourth Edition / January 10, 2015 |

| Repository |

|

| Marketing target | Operating systems research, networked environments, general-purpose use |

| Available in | English |

| Supported platforms | x86 / Vx32, x86-64, MIPS, DEC Alpha, SPARC, PowerPC, ARM |

| Kernel type | Monolithic |

| Influenced by | Research Unix, Cambridge Distributed Computing System |

| Default user interface |

rio / rc |

| License | 2021: MIT 2014: GPL-2.0-only 2002: LPL-1.02 2000: Plan 9 OSL |

| Succeeded by | Inferno Other derivatives and forks |

Plan 9 from Bell Labs is a special computer operating system created by smart people at Bell Labs in the 1980s. It was based on ideas from an older system called UNIX. Since 2000, anyone can use and change Plan 9 for free because it's open-source. The last official version came out in early 2015.

Plan 9 took a big idea from UNIX: 'everything is a file'. This means everything, even parts of the computer network, acts like a file. It also changed how computers handle input and output. Instead of old-fashioned text terminals, Plan 9 uses a windowing system with a graphical user interface. It also brought in new ideas like capability-based security (which controls what programs can do) and a special log-structured file system called Fossil. Fossil can take "snapshots" of your files and keep track of their history.

The name Plan 9 from Bell Labs comes from a famous 1957 science fiction movie called Plan 9 from Outer Space. Even today, computer researchers and hobbyists still use and work on Plan 9.

Contents

How Plan 9 Started

Plan 9 from Bell Labs began in the late 1980s. It was developed by the same group at Bell Labs that created Unix and the C programming language. The first team leaders included Rob Pike, Ken Thompson, Dave Presotto, and Phil Winterbottom. Dennis Ritchie, who helped create Unix, also supported the project. Many other famous developers contributed over the years.

Plan 9 became the main system for operating system research at Bell Labs, replacing Unix. It explored new ways to make computers easier to use, especially in multi-user environments where many people use the same system.

In 1992, Bell Labs shared Plan 9 with universities. Three years later, in 1995, it was made available for companies to buy. The developers didn't expect it to replace other popular operating systems.

By 1996, Bell Labs' owner, AT&T, focused less on Plan 9. They started working on a new system called Inferno. Later, in the late 1990s, Bell Labs' new owner, Lucent Technologies, stopped selling Plan 9.

In 2000, a third version of Plan 9 was released for free under an open-source license. A fourth version followed in 2002 with a new free software license. The final official release of Plan 9 happened in early 2015.

A community of users and developers, including people who used to work at Bell Labs, still makes small daily updates. Bell Labs used to host the development. The source code can be accessed over the network, allowing existing Plan 9 systems to update themselves. There's also a place where people share other programs and tools they've made for Plan 9.

Since Bell Labs moved on to other projects, official development of Plan 9 stopped for a while. However, on March 23, 2021, the Plan 9 Foundation took over the copyright from Bell Labs, and development started again. There's also an unofficial version called 9front, where people actively add new features every month. For example, 9front has added Wi-Fi and audio drivers, USB support, and even a game emulator. Other operating systems like Harvey OS and Jehanne OS have also been inspired by Plan 9.

| Date | Release | What Happened |

|---|---|---|

| 1992 | Plan 9 1st edition | Released by Bell Labs to universities |

| 1995 | Plan 9 2nd edition | Released by Bell Labs for non-commercial purposes |

| 2000 | Plan 9 3rd ed. (Brazil) | Released by Lucent Technologies as open source |

| 2002 | Plan 9 4th edition | Released by Lucent Technologies under a new free software license |

How Plan 9 Works

Plan 9 is a distributed operating system. This means it's designed to make many different computers, even if they are far apart, work together as one big system. Usually, people using Plan 9 work at terminals with a window system called rio. These terminals connect to powerful "CPU servers" that do all the heavy computing. Special "file servers" store all the permanent data.

The designers of Plan 9 built it on two main ideas:

- Each running program (called a process) has its own view of the name space. This is like its own personal map of all the computer's resources, including files.

- There's a simple way for programs to talk to each other using a "message-oriented file system protocol."

The second idea means that programs can offer their services to other programs by creating "virtual files." When one program reads or writes to these virtual files, it's actually sending messages to another program. This is how Plan 9 makes everything, even devices and network connections, look like files.

For example, the window system in Plan 9 uses three special "pseudo-files" to control what you see and do:

- mouse: A program can read this file to know where your mouse is moving and when you click.

- cons: This file handles text input and output, like typing on the keyboard.

- bitblt: Writing to this file makes graphics appear on the screen.

When you open a new window, Plan 9 sets up a new name space for it. The mouse, cons, and bitblt files in that window are connected to the window system itself. This way, the window system gets all the input and output from your program and shows it on the screen. The program doesn't need to know if it's talking directly to the computer's hardware or to the window system; it just uses these special files.

Plan 9's distributed nature also uses these personal name spaces. For instance, the cpu command lets you start a session on a remote computer. It shares parts of your local name space, like your terminal's mouse, keyboard, and display, with the remote computer. This means programs running far away can still use your local screen and keyboard.

The 9P Protocol

All programs that offer services as files use a single, simple language called 9P. This reduces the need for many different ways for programs to talk to each other. 9P is a flexible protocol that sends messages between a server and a client. It's used for everything from talking to programs to managing the network. In 2002, it was updated and renamed 9P2000.

Unlike most other operating systems, Plan 9 doesn't have special ways to access devices. Instead, device drivers (the software that controls hardware) act like file systems. So, you can control hardware like a mouse or a printer by simply reading from or writing to files. This also makes it easy to share devices across a network: you just "mount" the device's file system onto another computer.

Union Directories and Namespaces

Plan 9 lets you combine files from different folders into one "union directory." This new directory acts like a collection of all the files from the original folders. If two original folders have files with the same name, the union directory will show both. When you try to open a file with a duplicate name, Plan 9 looks for it in a specific order.

You can create a union directory using the bind command. For example:

bind /arm/bin /bin bind -a /acme/bin/arm /bin bind -b /usr/alice/bin /bin

In this example, when you ask for a file from /bin, Plan 9 first looks in /usr/alice/bin, then in /arm/bin, and finally in /acme/bin/arm.

This idea of separate "namespaces" for each program often replaces the idea of a "search path" found in other systems. While the rc shell (Plan 9's main shell) still has a path variable, it's usually kept simple. Instead of changing the path, you combine directories using bind.

Also, the computer's core (the kernel) can keep different file system maps for each program. This means every program can have its own unique view of the file system. This can be used to create a secure, isolated environment for a program, similar to a chroot jail but even safer.

The way Plan 9 handles union directories has inspired similar features in other operating systems like 4.4BSD and Linux.

Special Virtual Filesystems

/proc

Instead of special commands for managing running programs, Plan 9 uses the /proc file system. Each running program appears as a folder inside /proc. These folders contain files that give you information about the program or let you control it.

This file system approach means you can manage programs using simple file commands like ls (to list files) and cat (to view file contents). However, you can't copy or move programs like regular files.

/net

Plan 9 doesn't have special commands for accessing network connections. Instead, it uses the /net file system. You control network connections by reading and writing messages to special "control files" within /net. For example, folders like /net/tcp and /net/udp are used to interact with those network protocols.

Unicode Support

To make handling different languages easier, Plan 9 uses Unicode throughout the system. Ken Thompson invented UTF-8, which became the main way Plan 9 stores text. The whole system was changed to use UTF-8 in 1992. UTF-8 works well with older text systems and allows for combining text from many different languages. Using one single UTF-8 encoding for all cultures means you don't have to switch between different character sets.

Combining Design Ideas

The design ideas of Plan 9 are most powerful when used together. For example, to create a network address translation (NAT) server (which helps multiple devices share one internet connection), you can create a union directory. This directory would combine the router's /net directory with its own /net.

Similarly, you could set up a virtual private network (VPN) by combining a remote computer's /net files into a union directory on your local machine. This lets you use the remote computer's network securely over the internet. A union directory with the /net files and special filters can also be used to create a firewall or to run an untrusted program safely in a sandbox.

By using these features together, Plan 9 makes it easy to build complex computer networks by simply combining existing file systems.

Programs for Plan 9

Because of how Plan 9 is designed, many tasks can be done using simple tools like ls, cat, grep, cp, and rm along with the rc shell (Plan 9's main command line).

Factotum is a program that helps with authentication and key management in Plan 9. It handles logging in and security details for other programs, so you don't have to remember many passwords.

Graphical Programs

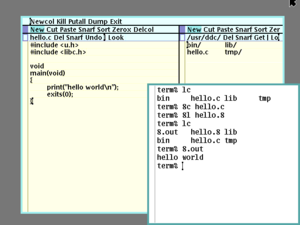

Unlike Unix, Plan 9 was built with graphics in mind. When you start a Plan 9 terminal, it runs the rio windowing system. Inside rio, you can open new windows and run the rc shell. When you start a graphical program, it takes over its window.

The plumber is a special tool that allows programs to communicate with each other across the system, creating a kind of system-wide hyperlinking.

Sam and acme are the main text editors used in Plan 9.

Storage System

Plan 9 supports several file systems, including Kfs, Paq, Cwfs, FAT, and Fossil. Fossil was made specifically for Plan 9 at Bell Labs. It can take "snapshots" of your data, which is like saving a specific version of your files. Fossil can work directly with a hard drive or with Venti, which is a system for long-term data storage.

Software Development

Plan 9 comes with its own special compilers and programming languages. It also has a set of libraries and its own windowing system. Most of Plan 9 is written in a version of the C programming language. The compilers for this language were made to be easily moved to different computer systems.

An older programming language called Alef was part of the first two versions of Plan 9. However, it was later removed and replaced with a way to create threads (smaller parts of a program that can run at the same time) in C.

Unix Compatibility

Even though Plan 9 was a new step for Unix ideas, it wasn't designed to be compatible with existing Unix programs. Many of Plan 9's command-line tools have the same names as Unix tools, but they work differently.

Plan 9 can run some POSIX applications (programs that follow a certain standard) using something called the ANSI/POSIX Environment (APE). APE provides an interface similar to ANSI C and POSIX. The people who made APE even used it to get the X Window System (X11) to run on Plan 9, but they don't include X11 because it's too much work to support. Some Linux programs can also run on Plan 9 with a "linuxemu" (Linux emulator), but it's still being worked on. On the other hand, a tool called Vx32 lets a slightly changed Plan 9 kernel run as a program inside Linux, which means you can run Plan 9 programs without changing them.

Licenses

Since the Fourth Edition was released in April 2002, the full source code of Plan 9 from Bell Labs has been available for free under the Lucent Public License 1.02. This license is considered an open-source license by the Open Source Initiative (OSI) and a free software license by the Free Software Foundation.

In February 2014, the University of California, Berkeley, was allowed by Alcatel-Lucent (who owned the copyright at the time) to release all Plan 9 software under the GPL-2.0-only.

On March 23, 2021, the ownership of Plan 9 moved from Bell Labs to the Plan 9 Foundation. All previous versions of Plan 9 are now licensed under the MIT License, which is a very open and permissive license.

See also

In Spanish: Plan 9 para niños

In Spanish: Plan 9 para niños

- Alef (programming language)

- Rendezvous (Plan 9)

- Inferno (operating system)

- Redox (operating system)

- Minix

- HelenOS