Qazi Azizul Haque facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Qazi Azizul Haque

|

|

|---|---|

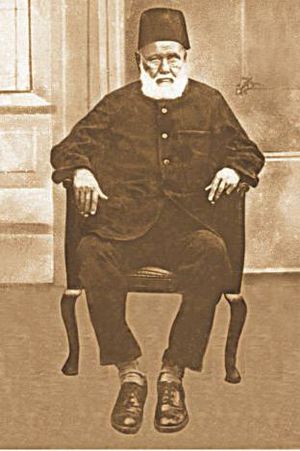

Haque in Motihari, Bihar, in 1929

|

|

| Born | c. 1872 |

| Died | 1935 (aged 62–63) |

Khan Bahadur Qazi Azizul Haque (Bengali: কাজি আজিজুল হক; 1872 – 1935) was a brilliant inventor and police officer from Bengal in British India. He is famous for helping to create the Henry Classification System for fingerprints. This system helps identify people using their unique fingerprints and is still used today! Haque created the important math behind this system.

Contents

Early Life and Learning

Qazi Azizul Haque was born in 1872 in a village called Paigram Kasba. This village was in the Khulna area of what was then the Bengal Presidency. Today, this area is part of Bangladesh. Sadly, his parents died in a boat accident when he was very young.

When he was just 12 years old, he left his home. He traveled to Kolkata, a big city. There, he met a kind family who were amazed by how good he was at math. They helped him get a proper education.

School and Police Work

Haque studied math and science at Presidency College, Kolkata. In 1892, a police officer named Edward Henry from the Calcutta Police needed help. He wrote to the college, asking for a student who was great at statistics. The principal suggested Haque.

Henry hired Haque as a police sub-inspector. At first, Haque was in charge of setting up a system called anthropometry in Bengal. This system tried to identify people by measuring their body parts. Later, when the area of Bihar became separate from Bengal, Haque chose to join the Bihar Police Service.

How Fingerprints Changed Policing

Haque wasn't happy with the old body-measurement system. He wanted a better way to identify people. So, he started working on his own system using fingerprints.

He came up with a special math formula. This formula helped sort fingerprint cards into 1024 different groups. Imagine having 1024 little boxes, and each fingerprint could be quickly put into the right box!

By 1897, Haque had collected 7000 sets of fingerprints. His method was simple to learn and had fewer mistakes than the old systems. Even with hundreds of thousands of fingerprints, his system could quickly find a match.

- Finding a criminal's record using the old body-measurement system took about an hour.

- Using Haque's fingerprint system, it took only five minutes!

Haque's boss, Edward Henry, saw how amazing this new system was. He asked the government to check it out. A special committee looked at the fingerprint system. They agreed that fingerprints were much better than body measurements because they were:

- Simpler to use.

- Cheaper to set up.

- Faster to work with.

- More accurate and certain.

Fingerprints became the new best way to identify criminals!

Who Got the Credit?

The fingerprint classification system became known as the Henry Classification System. However, many people believe that Haque's work was key to its success.

Hem Chandra Bose, another Indian police officer, also worked with Haque and Henry. He helped create a way to send fingerprint information using telegraph codes.

Years later, Haque asked the British government for recognition and payment for his work. Edward Henry did publicly say that Haque had helped a lot. He also later acknowledged Bose's contributions.

Many sources support Haque's important role:

- A newspaper called The Statesman wrote in 1925 that "A Muhammadan Sub-Inspector played an important and still insufficiently acknowledged part in fingerprint classification." This was about Haque.

- A government official named J.D. Sifton wrote in 1925 that Haque "evolved his primary classification which convinced Sir E.R. Henry that the problem... could be solved."

- Henry himself wrote in 1926 that Haque "contributed more than any other member of my staff... to bringing about the perfecting of a system of classification."

- The Home Department of the Government of India noted that Haque "actually himself devised the method of classification which is in universal use."

In 1912, when Henry visited India, he gave an award to Haque. Henry reportedly praised Haque as "the man mainly responsible for the new world wide fingerprint system of identification."

Haque received the title of Khan Shahib in 1913 and Khan Bahadur in 1924. Bose received similar honors. Both also received 5,000 rupees each for their amazing work.

Because of all this evidence, some researchers suggest that the system should be called the Henry-Haque-Bose System. While this hasn't happened yet, the UK Fingerprint Society has created a research award named after Haque and Bose to honor their contributions.

Clive Thompson, writing in Smithsonian magazine in 2019, also highlighted Haque's unique contribution. He noted that Haque developed an "elegant system that categorized prints into subgroups based on their pattern types such as loops and whorls." This made it possible to find a match in just five minutes.

Family Life

After retiring from his police work, Qazi Azizul Haque settled in Motihari, a place in Bihar Province. He passed away there and was buried.

He had eight children who survived him: four sons (Aminul, Asirul, Ekramul, and Motiur) and four daughters (Akefa, Amena, Arefa, and Abeda). After the partition of India, his wife, Jubennessa, and their children moved to East Pakistan and West Pakistan. Today, his family lives in many different countries, including Bangladesh, Pakistan, the UK, Australia, North America, and the Middle East.