Raising of school leaving age in England and Wales facts for kids

| Initial | 1880 |

|---|---|

| Latest | 2017 |

| Related Acts: |

|

| See raising of school leaving age for worldwide overview | |

The raising of the school leaving age (often called ROSLA) is a term used in the United Kingdom for when the government changes the age at which young people can leave school. These changes happen in England and Wales and are set by special laws called Education Acts.

Since 1880, when schooling first became required, the leaving age has gone up many times. These increases often aimed to help young people get more skills. This way, they would be better prepared for jobs. In 1880, children aged 5 to 10 had to go to school. The age then went up to 11 in 1893, 12 in 1899, 14 in 1918, 15 in 1947, and 16 in 1972. More recently, in England only, it went up to 17 in 2013 and 18 in 2015.

Contents

How the School Leaving Age Changed

| Age | England | Wales | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 1880 | See Elementary Education Act 1880 | |

| 11 | 1893 | ||

| 12 | 1899 | ||

| 13 | 1918 | See Education Act 1918 | |

| 14 | |||

| 15 | 1947 | See Education Act 1944 | |

| 16 | 1972 | ||

| 17 | 2013 | n/a | See Education and Skills Act 2008 |

| 18 | 2015 | ||

Schooling in the 1800s

The Elementary Education Act 1870 was for England and Wales. It made schooling required for children under 13. However, local school boards decided if it was compulsory in their area. By 1873, about 40% of schools made it mandatory.

If a school board thought education was a problem, they could set up rules. These rules, approved by Parliament, could make attendance required. Parents who didn't send their children could be fined. There were exceptions for illness or living far from a school. Children who had already reached a certain learning level could also be exempt.

The Elementary Education Act 1880 made school attendance required for children aged 5 to 10. It was hard to make sure poorer children went to school. Many families needed their children to work to earn money. "Attendance Officers" visited homes, but this often didn't work well. Children under 13 who worked needed a certificate. This showed they had met the "educational standard." Employers who hired children without this certificate faced penalties.

In 1893, the Elementary Education (School Attendance) Act raised the leaving age to 11. Later that year, this rule also included blind and deaf children. Before this, they had no official way to get an education. In 1899, the school leaving age went up again to 12.

Schooling in the 1900s

After 1900, the Board of Education wanted all children to stay in school until age 14. But many children could still leave at 13, or even 12, due to local rules. Many working-class parents didn't think more schooling was useful. They felt basic reading and math were enough for their children's future jobs.

Experts worried that boys leaving school early took "dead-end" jobs. These jobs paid well at first but had no chance for growth. They feared these boys would become unable to find good work later. There were also worries that children were becoming too independent too young. In 1902, local education authorities took over from school boards.

Education Between the World Wars

In 1918, education became required for children aged 5 to 14. The Education Act 1918, also known as the Fisher Act, made this law. It also planned for part-time schooling for 14- to 18-year-olds. There were ideas to expand higher education too. But after World War I, the government cut spending. This made the plans for older students difficult to achieve. This act was the first to plan for young people to stay in education until age 18. The 1918 act was fully put into action after another law was passed in 1921.

In 1933, the House of Commons talked about raising the leaving age to 15. This was to control how many children went straight into jobs after school. After the war, the number of births went up a lot. By 1920, it was the highest ever. But then it fell. This meant that in 1933, many children were about to leave school. Far fewer were starting school at young ages. It was thought that nearly half a million children could be looking for jobs by 1937. This was a big jump from 55,000 in 1934.

The proposed law allowed for some exceptions. Local education authorities could approve work certificates. This was for suitable jobs, with rules on how many hours could be worked. Some politicians believed this would help both education and jobs. They also thought it would not cost taxpayers too much money.

Post-War Education Changes

In 1944, the Education Act 1944 raised the school leaving age to 15. It also brought in the Tripartite System. This law was supposed to start in 1939. But World War II delayed it. It finally began in April 1947. This act also suggested part-time education for all children until age 18. But this idea was dropped to save money after the war.

The comprehensive school system has mostly replaced the Tripartite System in England.

Why the Age Was Raised

The government's view on education changed. They felt that leaving school at 14 was not enough. They believed that 14 was when young people truly started to understand learning. It was also when adolescence was at its peak. It seemed like the worst age to suddenly switch from school to work. In 1938, about 80% of children left school at this age. Many had only primary school education.

There were worries about having fewer young workers. But people hoped that more skilled workers would make up for the loss of unskilled labor.

Effects of the 1944 Act

This act brought in the 11+ examination. This test decided if a child would go to a grammar school, secondary modern school, or technical college. This was part of the Tripartite System. Today, most of the United Kingdom no longer uses this test. Only a few areas in England and Northern Ireland still do.

Society and ideas about education have changed a lot. Now, it's understood that all children deserve the same chances to learn. This means every child should be able to get secondary school qualifications. This is true no matter their background or how fast they learn.

Leaving Age Raised to 16

In 1959, the Minister of Education, David Eccles, looked at education for young people aged 15 to 18. He wanted to focus on promises from the Education Act 1944. These included raising the leaving age to 16. It also meant creating colleges for required part-time attendance up to age 18. It was clear that an extra year of school should offer "new and challenging courses." It shouldn't just be more of the same. At this time, half of the army recruits who were very capable had left school at 15.

In 1964, plans began to raise the school leaving age to 16. These plans were delayed in 1968. Finally, in 1971, the decision was made. The new age limit would start on September 1, 1972. Along with raising the age, 1972 also saw the Education (Work Experience) Act. This allowed local education authorities to arrange work experience for the new final-year students.

In some areas, these changes led to middle schools opening in 1968. Students stayed in primary or junior school for an extra year. This meant secondary schools in these areas had about the same number of students. In other places, bigger changes happened. Middle schools for pupils up to 13 opened in smaller secondary school buildings. Other schools took students over 13. By 2010, there were fewer than 300 middle schools in England. Their number has been falling since the mid-1980s.

ROSLA Buildings

For secondary schools without a middle school, fitting in the new 5th-year students was hard. A common answer was to give schools a pre-fabricated building. These were often called ROSLA buildings or ROSLA blocks. They gave schools the space to handle the new group of 5th-year students. This was popular because it was cheap to build and quick to put up. Many were supplied by F. Pratten and Co Ltd.

ROSLA buildings came in self-assembly kits. They were put together quickly, sometimes in days. They were not meant to last a long time. However, some have lasted much longer than planned. Many ROSLA buildings looked similar from the outside. The only difference was how rooms were separated inside. School leaders decided on the room layout. So, many walls were added after the main building was put up.

Most schools have replaced their ROSLA building(s). But many schools still use them today.

Education Act 1996

Between 1976 and 1997, the rules for leaving school were:

- If a child turned 16 between September 1 and January 31, they could leave at the end of the Spring term (around Easter).

- If a child turned 16 between February 1 and August 31, they could leave on the Friday before the last Monday in May.

The Education Act 1996 set a new single school leaving date. This started in 1998 and continues today. It is the last Friday in June of the school year when the child turns 16.

Schooling in the 2000s

England

2006 Education Reform Act

In November 2006, reports suggested that Education Secretary Alan Johnson was thinking about raising the school leaving age in England to 18. This would be over 40 years after the last increase in 1972. He pointed out that there were fewer unskilled jobs. Young people needed more skills for modern work.

Participation Age

A year later, in November 2007, Prime Minister Gordon Brown announced the government's plans. These plans included a duty for parents to help their children stay in education or training until their 18th birthday. The plans also aimed to improve apprenticeships and help children in care.

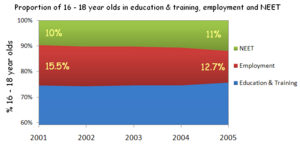

The Education and Skills Act 2008 came into force in 2013. It first required young people to stay in education or training until they turned 17. Then, in 2015, the age was raised to 18. This was called raising the "participation age." It's different from the "school leaving age," which stays at 16. To count as participation, young people must be in education or training for at least one day a week. Local councils must make sure there are suitable places available.

Why the Age Was Raised

Figures from June 2006 showed that 76.2% of young people aged 16–18 were already in further education or training. This meant the change would only affect about 25% of young people. These were the ones who might have looked for a job right after finishing school. The law didn't mean young people had to stay in secondary school. Instead, they had to continue their education full or part-time. This could be in sixth form, college, or work-based training.

When the idea was first proposed, 80% of 16-year-olds already stayed in full-time education. Or they went on a government-funded training course. A survey of 859 people showed that 9 out of 10 supported the plans.

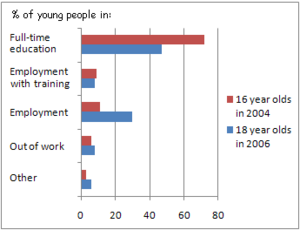

A report from the Department for Education and Skills (DfES) showed that 70% of 16-year-olds stayed in full-time education. But this dropped to less than 50% by age 18. Most found unskilled jobs. Even fewer found jobs related to their training. There was also a small rise in unemployment by age 18. The government hoped to reduce this with the new law. They called young people who were unemployed and not in education or training "NEET" (Not in Education, Employment or Training). In 2006, an extra 7% of 16-year-olds were NEET. This went up to 13% for 18-year-olds.

The government said that the number of unskilled jobs had fallen. There were 8 million in the 1960s, but only 3.5 million by 2007. They predicted a further drop to 600,000 by 2020. They believed that extending required education until age 18 would help more young people find skilled employment. In March 2007, Chancellor Gordon Brown said that about 50,000 teenagers would get a training allowance. This was to encourage them to join college courses. He estimated that the number of apprenticeships would double to about 500,000 by 2020. Most of these (80%) would be in England. This would be a big increase from the 250,000 apprenticeships available then.

Who Disagreed

While the government wanted to make these changes, many people were against them. Some argued it limited personal freedom. Usually, requiring school attendance is justified because young children can't make good choices. But the 16–18 age group is tricky. They are seen as adults in some ways, but have extra rules and protections in others.

Members of the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats disagreed with using legal punishments. They felt that forcing young people was the wrong way to get them to participate. A spokesperson for the DfES said the plans were not about "forcing young people." They said, "we are letting young people down if we allow them to leave education and training without skills at the age of 16."

However, in November 2007, the Prime Minister's speech suggested that students who didn't follow the new laws could face fines or community service. Earlier ideas of prison were dropped. Local Authorities would also need to make sure students were participating until age 18.

What Happened Next

A report in 2013 said that young people were not getting enough support from the education system. It especially criticized the lack of information and advice for 14-19 year olds. The government hoped the changes would help prevent crime. They believed many young people who left school turned to crime. This was because they couldn't find good work due to a lack of skills.

In 2015, the percentage of 16–18 year olds classified as NEET fell to 7.5%. This was the lowest since 2000. In 2021, 91.5% of 16- and 17-year-olds in England were in full-time education or an apprenticeship. Another 4.4% were in other training, and 5% were NEET. A 2020 report showed that the number of 16- to 17-year-olds in paid jobs in the UK had dropped. It went from 48.1% in 1997-99 to 25.4% in 2017-19.

Wales

The creation of the National Assembly for Wales in 1999 led to different education rules in Wales and England. The 2008 Education and Skills Act gave the Assembly the power to make similar changes. A spokesperson for the Welsh Assembly said they wanted to encourage more young people to stay in education. But they did not want to force them. So, young people in Wales are not required to continue education or training after school. In 2020, about 10% of young people in Wales aged 16 to 18 were not in education, employment, or training. For England in 2019, this number was 6.6%.

See Also

- School leaving age

- Newsom Report

- Education in England

- Education in Wales

- Compulsory education

- Tripartite System

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |