Roberto Cofresí facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Roberto Cofresí

|

|

|---|---|

Monument of Roberto Cofresí located in Boquerón Bay.

|

|

| Born | June 17, 1791 |

| Died | March 29, 1825 (aged 33) |

| Piratical career | |

| Nickname | El Pirata Cofresí |

| Other names | Cofrecina(s) |

| Type | Caribbean pirate |

| Allegiance | None |

| Rank | Captain |

| Base of operations | Barrio de Pedernales Isla de Mona Vieques |

| Commands | Flotilla of unidentified vessels Caballo Blanco Neptune Anne |

| Battles/wars | Capture of the Anne |

| Wealth | 4,000 pieces of eight (hidden remnants of a larger fortune) |

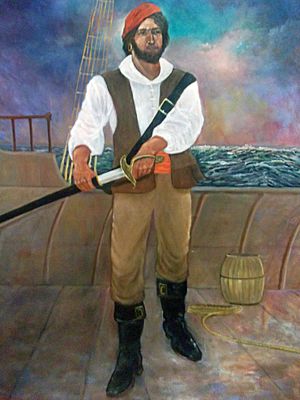

Roberto Cofresí y Ramírez de Arellano (June 17, 1791 – March 29, 1825), also known as El Pirata Cofresí, was a famous pirate from Puerto Rico. He was born into a noble family, but his family became poor because of the tough times on the island. Roberto started working at sea when he was young. This helped him learn a lot about the ocean and the area. But his pay was low, so he decided to become a pirate.

During his time as a pirate, Cofresí was very good at avoiding capture. Ships from many countries, like Spain, the United Kingdom, and the United States, tried to catch him. He used small, fast ships, with his most famous one being a six-gun sloop named Anne. He preferred speed over big guns. His crews were small, usually 10 to 20 people. He often tried to outrun his pursuers. However, his group did fight the West Indies Squadron twice. They attacked the schooners USS Grampus and USS Beagle. Most of his crew came from Puerto Rico, but some joined from other islands and countries.

Local authorities found it hard to stop Cofresí. So, Spain teamed up with the West Indies Squadron and the Danish government to catch him. On March 5, 1825, they set a trap. This led to a sea battle where Cofresí had to leave his ship and escape on land. A local person recognized him, attacked him, and injured him. Cofresí was caught and put in prison. He tried to escape one last time by offering a hidden treasure to an official, but it didn't work. The pirates were sent to San Juan, Puerto Rico. A quick military court found them guilty and sentenced them to death. On March 29, 1825, Cofresí and most of his crew were executed by a firing squad.

After his death, many stories and myths grew about him. Most of these stories say he was like Robin Hood, stealing from the rich to give to the poor. This idea became a legend, and many people in Puerto Rico and the West Indies believe it. Some stories even say Cofresí was part of the Puerto Rican independence movement. His life, both real and mythical, has inspired songs, poems, plays, books, and movies. In Puerto Rico, many places like caves and beaches are named after him. A resort town in the Dominican Republic is also named Cofresí.

Contents

Early Life and Family

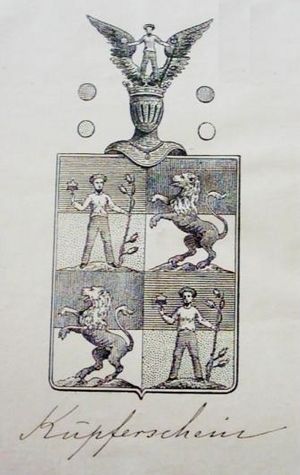

Roberto Cofresí came from a noble family. His family name, Kupferschein, came from Prague. They were recognized as nobles in 1549 and became very wealthy in Trieste. Roberto's grandfather held important jobs in the police and military. His father, Francesco Giuseppe Fortunato von Kupferschein, had a good education. He traveled to Frankfurt and met important people.

Francesco had to leave Trieste after a fight in 1778. He went to Barcelona and learned Spanish. By 1784, he settled in Cabo Rojo, Puerto Rico. This was a port town far from the capital, San Juan. It was a good place for trade, even illegal trade. Francesco's name was changed to Francisco José Cofresí, which was easier for locals to say. He married María Germana Ramírez de Arellano y Segarra. Her family was also noble and owned a lot of land in Cabo Rojo. They settled near the coast.

From Noble to Poor

The wars for independence in Latin America affected Puerto Rico. Sea trade became very difficult. Cabo Rojo's ports almost stopped working. People faced high taxes and problems from foreigners. Slaves even tried to escape by sea. Roberto Cofresí was born during these hard times. He was the youngest of four children. His mother died when he was four, and his aunt raised him. His father died in 1814, leaving little money. Roberto likely had no home or income.

In 1815, Roberto married Juana Creitoff. She was probably from Cabo Rojo, with Dutch parents. They moved into a house bought by Juana's father. But soon, her father lost his home in a fire, putting the family in debt. Three years later, Cofresí owned no property and lived with his mother-in-law. He had two sons, but both died soon after birth.

Even though he came from a respected family, Cofresí was not rich. He spent most of his time at sea, earning very little. He likely worked in fishing. In 1819, he was listed as a sailor. He helped move goods between towns. His brothers were also sea merchants.

Political changes in Spain affected Puerto Rico in the early 1800s. Many Europeans came to the island, changing the economy. Prices went up, and food was hard to get. Many people became poor and turned to crime. By 1816, local mayors were in charge of law enforcement. But crime, like highway robbery, continued to grow. In 1818, a high-security prison was built in San Juan.

Cofresí, despite his noble background, led a criminal group in San Germán. They stole cattle, food, and crops. He was linked to other noblemen involved in crime. The situation got worse when a hurricane hit in 1820, destroying crops. The governor ordered a crackdown on criminals. Cofresí was likely involved in a highway robbery in Yauco. This made the governor think officials were helping criminals.

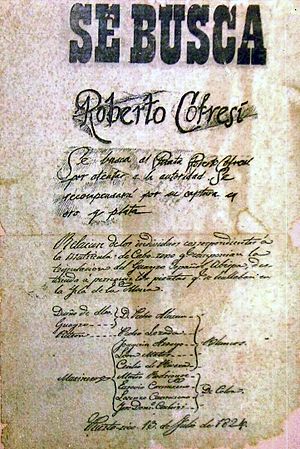

The government issued wanted posters for Cofresí. In July 1821, he and his gang were caught. They were tried in San Germán. While in prison, his only daughter, Bernardina, was born. Cofresí likely escaped during this time. He used his family connections to stay hidden. The Ramírez de Arellano family, who held many public jobs, protected him. He visited his wife and mother-in-law in secret.

Becoming a Pirate Legend

Building a Reputation

By 1823, Cofresí was likely working on a privateer ship called El Scipión. This ship was managed by his cousin. Historians believe he joined to avoid authorities and learn new skills. El Scipión used tricks, like flying the flag of another country, to surprise other ships. After a lawsuit affected the crew's pay, Cofresí turned to piracy. The exact reasons are unclear, but it was a time when many privateers were out of work.

Cofresí became the most important pirate in the Caribbean at that time. He was the last major target of anti-piracy efforts. While many pirates failed, Cofresí was known to have robbed at least eight ships and was linked to over 70 captures. He didn't have a strict pirate code, but his daring personality made him a strong leader. He reportedly had a rule: only those willing to join his crew could live. Cofresí had a large network of helpers and informants on land.

One of the first records of Cofresí's methods is from July 1823. A ship carrying coffee was taken by pirates to Isla de Mona. The captain and crew were forced to unload the cargo. Then, the pirates reportedly killed the sailors and sank the ship. Cofresí's brothers helped him move stolen goods. The pirates used coastal signals to communicate and warn each other of danger.

Some historians say Cofresí shared his loot with the poor, like a Puerto Rican Robin Hood. Others say any generosity was just for show. He reportedly held informal markets in Cabo Rojo to sell stolen goods. Local helpers made this process easier.

In October 1823, Cofresí attacked a fishing boat and stole money. He also led the capture of an American schooner named John. His group, armed with swords and muskets, stole cash, tobacco, and other supplies. Cofresí ordered the crew to go to Santo Domingo, threatening them if they went to Puerto Rican ports. But the captain went to Mayagüez and reported the attack.

It was clear some pirates were from Cabo Rojo. Undercover agents were sent to track them. The mayor asked for help because the pirate group was out of control. It was hard to arrest them because of their local supporters. The government demanded their capture. Cofresí was tracked to a beach, but he escaped. Only some stolen goods were found. A captured pirate linked Cofresí to the hijackings.

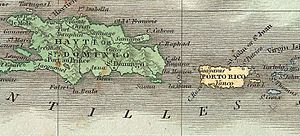

Cofresí's success was unusual because piracy had mostly ended. Governments had worked together to stop pirates. This made catching Cofresí a top priority. By late 1823, Cofresí moved his main base to Mona Island. This island had been a pirate hideout for over a century. Another pirate base was found on Saona Island, south of Hispaniola.

In November, sailors on El Scipión took over the ship and turned it into a pirate vessel. Cofresí was linked to this ship. He was also seen in eastern Hispaniola. On one trip, Spanish patrol boats caught the pirates. Cofresí reportedly ordered his ship to sink to create a distraction. This allowed him and his crew to escape in small boats. The sunken ship, said to be full of treasure, has never been found.

There's a story from 1823 about Cofresí and a young student named Pedro Gerónimo Goyco. Cofresí stopped Goyco's ship. When he learned Goyco's father was a friend, Cofresí freed the boy on a beach near Mayagüez. Goyco's father had helped Cofresí's family. Goyco later became an important leader against slavery.

Cofresí's actions caught the attention of American and British nations. The US Consul described the attacks to the Secretary of State. This led to Commodore David Porter sending ships to Puerto Rico to fight piracy. In November, Cofresí attacked another American ship, the William Henry.

The International Hunt for Cofresí

Cofresí attacked both local and foreign ships. This hurt the economy. Spain had lost most of its colonies, and Puerto Rico faced problems. Spain stopped giving out "letters of marque," which meant many sailors lost their jobs and joined pirates like Cofresí. Pirates flying the Spanish flag attacked foreign ships, causing diplomatic issues. The Spanish governor, Miguel Luciano de la Torre y Pando, made catching Cofresí a top priority. By December 1823, other countries joined the hunt, sending warships to the Mona Passage.

In January 1824, the governor ordered that pirates be tried quickly by military courts. He offered rewards for their capture. The US also sent ships, like the USS Weasel and USS Spark, to find the pirate base on Mona Island. They found and destroyed a small settlement there. But Cofresí quickly set up a new base on Mona.

Cofresí continued his attacks. He captured two more ships, Boniton and Bonne Sophie. The sailors were beaten and imprisoned. The governor ordered a more aggressive pursuit of pirates. He specifically asked for Cofresí to be captured. He knew Cofresí was protected by local officials in Cabo Rojo.

France also joined the hunt for Cofresí. They sent a frigate, Flora, to patrol the coast. But the attempts to catch him were unsuccessful. Cofresí bought a new ship, which became his pirate flagship. The way he bought it was suspicious, leading to an investigation of local officials. Several members of the Ramírez de Arellano family were charged with helping him.

Searches for Cofresí continued in Cabo Rojo and San Germán. Troops almost caught him at Pedernales, but he escaped on foot. His brother-in-law and another associate were captured. Authorities found hidden stolen goods in their homes. Cofresí's brother, Juan Francisco, and others were sent to San Juan.

The pirates fled south. In June 1824, Cofresí and his crew stole cattle and supplies from haciendas near Jobos Bay. The mayor of Guayama asked for military help, but there weren't enough weapons. The pirates then attacked the schooner San José y Las Animas, stealing most of its cargo. The governor was in the area at the time, keeping authorities busy. Stolen goods from the ship were later found in Cabo Rojo.

A group of volunteers went to Mona Island to ambush Cofresí. Most of the pirates were caught, but Cofresí was not with them. His second-in-command was killed. The volunteers returned with prisoners and the pirate's head and hand for identification. The Spanish government honored the volunteers. Cofresí reportedly escaped and continued his attacks.

The mayor of Ponce also searched for Cofresí, but failed. The governor ordered the destruction of any huts or abandoned ships that might help Cofresí escape. Authorities continued to track the pirates. One of Cofresí's associates was killed in a shootout. Many other associates were arrested and tried in San Juan.

The pirates stole a "sturdy, copper-plated boat" from Cabo Rojo. It was found later, with weapons and supplies, but the pirates had fled inland. Cofresí and a small crew captured two sloops off the coast of Guayama. He didn't plunder them, but instead asked for information. The US sent the USS Weasel to monitor the western waters. It found a pirate sloop, but the pirates escaped into dense vegetation.

In September 1824, Cofresí's crew stole from a Danish sloop near Isla Palominos. This made the Danish government send a warship. A hurricane then hit Puerto Rico, pushing Cofresí's ship towards Hispaniola. He and his crew were captured in Santo Domingo and sent to prison. But Cofresí and his men escaped twice! They broke locks and climbed down prison walls using ropes made from their clothes. They bought a new ship and sailed back to Puerto Rico, setting up a hideout in Vieques.

Cofresí Challenges the West Indies Squadron

By October 1824, Cofresí was the last major pirate threat. Many of his former crew members and other criminals escaped from jail and joined him. His new second-in-command was Bibián Hernández Morales, an expert knife fighter. At their peak, they had three sloops and a schooner. They hid in many coastal towns and reportedly flew the flag of Gran Colombia.

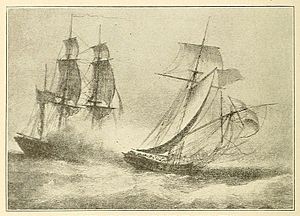

In October, Hernández Morales led a robbery in Saint Thomas, stealing US$5,000. The USS Beagle went after them. It found a pirate sloop and opened fire, but the pirates escaped inland. The international forces increased their patrols. Despite this, Cofresí became even bolder. In January 1825, Cofresí attacked the USS Grampus on the west coast. He fired muskets and ordered the schooner to stop. But when the Grampus fought back, Cofresí escaped into the night.

The pirates sailed east, robbing a house in Fajardo. Two days later, Cofresí attacked a Spanish sloop, San Vicente, with two sloops, firing muskets and blunderbusses. The San Vicente was heavily damaged but escaped.

In February 1825, Cofresí plundered the sloop Neptune. He fired muskets at the crew, and the owner fled, getting shot. Cofresí took Neptune as his new pirate ship. The mayor of Guayama increased patrols. Hernández Morales, leading another sloop, was captured by the Beagle after a battle. He was sent to St. Thomas for trial, but he escaped from prison.

Later that week, Neptune captured a Danish schooner. After the attack, Cofresí abandoned the ship at sea. It was found floating with broken masts. Cofresí then boarded another ship, plundering and abandoning it too.

Cofresí returned to Jobos Bay. On February 18, he captured a six-gun sloop called Anne (also known as Ana). The ship was owned by John Low, who had ordered it built. Cofresí and eight pirates secretly boarded the ship, forcing the crew to jump overboard. Cofresí reportedly took $20 from Low's pocket. Low's crew survived and reported the attack. Low had docked near a pirate hideout, and they wanted revenge after Hernández Morales was captured. Days later, Cofresí and his crew stole a cannon from a gunboat being built in Humacao.

After the hijacking, Anne became Cofresí's main ship. He used it to intercept a merchant ship near Vieques. The Spanish sent a small boat to find the pirates, but it was unsuccessful. Cofresí's last capture was on March 5, 1825, when he hijacked a boat in Salinas.

Capture and Trial

By spring 1825, Cofresí's group was the last big pirate threat in the Caribbean. John Low, the owner of the hijacked Anne, returned to Saint Thomas. A Puerto Rican ship reported seeing Cofresí. So, John D. Sloat, captain of the Grampus, asked the Danish governor for three international sloops. These ships, along with Grampus, formed a task force. They spotted Anne and decided to split up.

The ship San José y Las Animas found Cofresí the next day and launched a surprise attack. Cofresí, thinking it was a local merchant ship, ordered his crew to attack. But when Anne was close enough, San José y Las Animas opened fire. The pirates fought back but couldn't escape. Cofresí ran Anne aground and fled inland. He was injured and had two crew members with him. Half his crew was caught soon after.

Cofresí remained free until the next day. At midnight, a local soldier, Juan Cándido Garay, and two others spotted Cofresí. They ambushed him, and he was shot while fleeing. Despite his injury, Cofresí fought with a knife until the militia overpowered him.

After their capture, the pirates were held in Guayama before being moved to San Juan. Cofresí met with the mayor of Guayama, Francisco Brenes. He offered Brenes 4,000 pieces of eight (which he claimed to have hidden) for his freedom. This is the only historical mention of Cofresí having hidden treasure. Brenes refused the bribe. Cofresí and his crew were imprisoned in Castillo San Felipe del Morro in San Juan.

Military Trial

Cofresí had a military trial, called a council of war. He could only choose his lawyers, but their role was mostly a formality. The trial was very quick, which was unusual. It's believed the Spanish government rushed the trial because of international pressure. Other countries had complained about pirate attacks in Puerto Rican waters. The trial was based on the pirates' confessions, but how these confessions were obtained was not checked.

Cofresí confessed to capturing several ships. He insisted he didn't know where the ships or crews were now. He also said he had never killed anyone. Other pirates supported his story. However, one report said Cofresí admitted off the record that he had killed almost 400 people, but no Puerto Ricans. He also confessed to burning a ship's cargo to mislead authorities.

Death and Legacy

On the morning of March 29, 1825, Cofresí and his crew were executed by a firing squad. Many people watched the public execution. Catholic priests were there to offer comfort. The pirates were shot as they prayed. While Fort San Felipe del Morro is the usual location, some say it happened near Convento Dominico. It is said that Cofresí refused to have his eyes covered. He reportedly said, "I have killed hundreds with my own hands, and I know how to die. Fire!"

Cofresí and his men were buried near the Santa María Magdalena de Pazzis Cemetery. They were not buried inside the Catholic cemetery because they were criminals. Spanish authorities continued to arrest Cofresí's helpers until 1839.

Cofresí's family was charged for the trial expenses. His wife, Juana Creitoff, was left with the debt. His brothers distanced themselves from him. Cofresí had wasted his treasure, so the only thing the government could take was his servant, Carlos. Carlos was sold to pay for the trial costs. Juana Creitoff died a year later.

Cofresí's daughter, Bernardina, later married and had seven children. His family line continues in Cabo Rojo today. One famous descendant was Ana González, also known as Ana G. Méndez. She was Cofresí's great-granddaughter. She was interested in education and founded the Puerto Rico High School of Commerce in the 1940s. This school grew into the Ana G. Méndez University System, the largest group of private universities in Puerto Rico.

Items linked to Cofresí have been preserved. His birth certificate is at San Miguel Arcángel Church. Earrings said to have been worn by Cofresí are now at the National Museum of American History. Many documents about Cofresí are kept in archives in Puerto Rico and other countries. However, official documents about his trial and execution have been lost.

Modern Views of Cofresí

Many stories about Cofresí have become romanticized. During his life, Spanish authorities tried to make him seem like a scary "terror of the seas." This, along with his daring acts, turned him into a legendary figure. The legends often mix facts with fiction. Stories about his background, personality, and loyalties change. But these myths are so common that many people believe them as truth.

The myths about Cofresí usually fall into two groups. One group shows him as a generous thief or anti-hero. These stories say he stole from the rich to help the poor. They try to explain his piracy by saying it was due to poverty or a desire to restore his family's honor. He is often shown as a hero who fought against unfairness and corruption. Some stories even say he protected children, women, and the elderly, and supported independence.

The other group of legends describes Cofresí as evil. These stories often link him to magic or deals with the Devil. They highlight his cruelty when he was alive or say his ghost still roams. His ghost is said to have a fiery glow or special powers. It protects his hidden treasures or wanders without purpose. Merchants often portray him as a villain. Stories that show him as good are more common near Cabo Rojo. In other parts of Puerto Rico, stories focus on his treasure and show him as a ruthless pirate. Most hidden treasure stories teach a lesson against greed. Those who try to find the treasure are often killed or attacked by his ghost. Many places in Puerto Rico and Hispaniola are rumored to have his hidden treasure.

In the 20th century, interest in Cofresí grew as a tourist attraction. Towns in Puerto Rico highlight their connection to him. Beaches and sports teams are named after him, especially in Cabo Rojo, where there is a monument in his honor. A resort town in the Dominican Republic is also named Cofresí. His name has been used for many products and businesses. Puerto Rico's first seaplane was named after him. There have been several attempts to make movies about his life, based on the legends.

Songs, poems, and plays have been made from the oral stories about him. Many historians have also studied the real Cofresí and the legends. His story has appeared in many newspapers and magazines.

See also

In Spanish: Roberto Cofresí para niños

In Spanish: Roberto Cofresí para niños

- List of Puerto Ricans

- List of pirates

- Miguel Enríquez (privateer)

- Folklore of Puerto Rico

- Folk hero

| Madam C. J. Walker |

| Janet Emerson Bashen |

| Annie Turnbo Malone |

| Maggie L. Walker |