Rodrigo de Arriaga facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Rodrigo de Arriaga

|

|

|---|---|

Disputationes theologicae, Antwerp, 1643

|

|

| Born | 17 January 1592 |

| Died | 7 June 1667 (aged 75) |

| Education | Charles University (Th.D., 1624) |

| Era | 17th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Scholasticism Conceptualism |

| Institutions | |

|

Main interests

|

Metaphysics, logic, natural philosophy |

|

Influenced

|

|

Rodrigo de Arriaga (born January 17, 1592 – died June 7, 1667) was an important Spanish philosopher and theologian. He was also a member of the Jesuit order. Arriaga was known as one of the most important Spanish Jesuits of his time. He was a leading thinker in a philosophical style called nominalism, which was popular after the ideas of Francisco Suárez.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Rodrigo de Arriaga was born in 1592 in Logroño, a city in Spain. When he was 14 years old, on September 17, 1606, he joined the Society of Jesus, also known as the Jesuits.

He studied philosophy and theology under a teacher named Pedro Hurtado de Mendoza. Arriaga then began teaching himself. From 1620 to 1623, he taught philosophy at the University of Valladolid. In 1624, he taught theology there. He also taught theology at the University of Salamanca from 1624 to 1625.

Life in Prague

In 1625, Arriaga moved to the Charles University in Prague. He stayed there for the rest of his life. He became a professor of theology in 1626, soon after he arrived. He taught until 1637.

After teaching, he became the prefect of studies for the theology department. This meant he was in charge of the studies. He held this job until 1642. Then, he became the chancellor of the Clementinum, a famous college in Prague. He stayed in this role until 1654.

In 1654, he became the prefect of studies again and kept this position until he died. Arriaga became very famous, not just in Spain but all over Europe. People often said, "To see Prague, to hear Arriaga," because he was such a great teacher.

He was highly respected by important leaders like Pope Urban VIII, Pope Innocent X, and Emperor Ferdinand III. Arriaga died in Prague on June 17, 1667.

Saving Manuscripts

Arriaga was good friends with the Belgian mathematician Grégoire de Saint-Vincent. In 1631, during a battle, soldiers attacked Prague and set parts of the city on fire. It was Arriaga who saved Saint-Vincent's important writings from being destroyed.

His Philosophical Approach

Arriaga is an important figure in the history of modern philosophy. He tried to update and strengthen medieval scholasticism, which was a way of thinking and teaching. His main philosophical work, Cursus Philosophicus, was a very skillful attempt to do this.

Arriaga carefully studied the new ideas of thinkers who disagreed with the old ways. He tried to change and adapt the old ideas of logic, metaphysics, and especially natural philosophy to fit modern times. He went further than most other scholastic philosophers in trying to find a middle ground.

Some people who strongly followed the old ways criticized him. They said he was a skeptic and that he purposely made arguments against his own ideas seem weaker. However, others, like the philosopher Jan Marek Marci, used Arriaga's new ideas to show that the old philosophy had weaknesses.

Influence and New Ideas

Arriaga had very new ideas in metaphysics and natural philosophy. For example, he supported the idea of heliocentrism, which says the Earth goes around the Sun. This was despite rules from the church at the time. He looked at old scholastic ideas with a critical eye and was open to nominalism.

He disagreed with the idea that you could prove God's existence just by thinking about it. He also believed that the immortality of the soul could only be shown as likely, not certain.

Interest in Science

Arriaga showed a strong interest in the new scientific thinking of his time. He was familiar with new ways of doing experiments, which was unusual for scholastic thinkers. He believed that space between planets was fluid, like a liquid. He also gave up many old scholastic ideas about natural philosophy. He defended new thinkers in philosophy.

He believed that philosophers should have more freedom to explore new ideas. In his book Cursus Philosophicus (1632), he argued for new opinions. He asked why new thinkers couldn't come up with new conclusions, since they had studied so much since ancient times. He thought that old ideas were not always true just because they were old. He found it amazing how many old ideas had little proof and were based on misunderstandings of thinkers like Aristotle.

Impact on Other Thinkers

The French philosopher Pierre Bayle praised Arriaga for his method of questioning ideas. Bayle thought this was very important for philosophy. Arriaga greatly influenced the Czech physician Jan Marek Marci. He also influenced the Italian scholar Valeriano Magni and the Spanish philosopher Juan Caramuel y Lobkowitz.

The famous German philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz used Arriaga's works a lot. It is also thought that René Descartes's ideas about how things expand and shrink were influenced by Arriaga.

Debates About His Work

However, Arriaga's work sometimes caused arguments. He was accused of supporting an idea about quantity that said things were made of points. This idea was often rejected by leaders of the Jesuit order. They thought it went against certain religious beliefs.

Even though the Jesuits tried to stop this idea from spreading, it continued to be discussed in their books. Arriaga was even named as a source for this idea spreading in Germany. This was likely because his philosophy textbook, Cursus Philosophicus, was widely read there.

Major Works

Arriaga published two very large and important works:

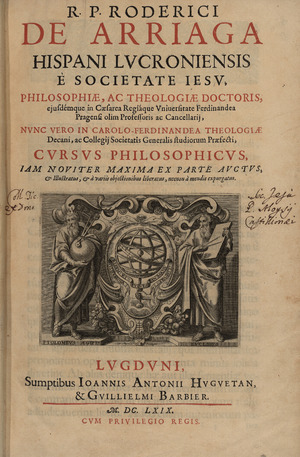

- Cursus Philosophicus: This was his main philosophy textbook. It was reprinted many times in different cities, including Paris (1637, 1639) and Lyon (1644, 1647, 1653, 1659, 1669).

- Disputationes Theologicae in Summam Divi Thomae: This was a long series of discussions about the ideas of Thomas Aquinas, a famous theologian. It was published in several volumes over many years:

- Volumes I and II (about the First Part) were published in Antwerp in 1643 and Lyon in 1644 and 1669.

- Volumes III and IV (about the First-Second Part) were published in Antwerp in 1644 and Lyon in 1669.

- Volume V (about the Second-Second Part) was published in Antwerp in 1649 and Lyon in 1651.

- Volumes VI, VII, and VIII (about the Third Part) were published in Antwerp from 1650 to 1655 and Lyon from 1654 to 1669.

See also

In Spanish: Rodrigo de Arriaga para niños

In Spanish: Rodrigo de Arriaga para niños

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |