Francesco Sforza Pallavicino facts for kids

Quick facts for kids His Eminence Sforza Pallavicino |

|

|---|---|

Giovanni Maria Morandi (attributed to), Portrait of Cardinal Sforza Pallavicino, 1663 (oil on canvas, British embassy, Vatican City, Holy See)

|

|

| Diocese | Diocese of Rome |

| Appointed | 9 April 1657 |

| Reign ended | 4 June 1667 |

| Orders | |

| Created Cardinal | 9 April 1657 |

| Rank | Cardinal-Priest of San Salvatore in Lauro |

| Personal details | |

| Born | November 28, 1607 Rome, Papal States |

| Died | 4 June 1667 (aged 59) Rome |

| Buried | Sant'Andrea al Quirinale |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Denomination | Roman Catholic |

| Parents | Alessandro Pallavicino Francesca Sforza di Santa Fiora |

| Alma mater | Roman College

Philosophy career |

| Education | Roman College (Ph.D., 1625; D.Th. 1628) |

| Era | 17th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Aristotelianism Scholasticism Conceptualism |

| Institutions | Roman College |

| Doctoral advisor | Juan de Lugo |

| Notable students |

|

|

Main interests

|

Natural philosophy, metaphysics, epistemology, aesthetics |

Francesco Maria Sforza Pallavicino (born November 28, 1607, died June 4, 1667) was an important Italian figure. He was a cardinal, a philosopher, and a church historian.

He taught philosophy and theology at the Roman College. He was also part of important groups like the Accademia dei Lincei. Pallavicino wrote many influential books on philosophy and theology. His history of the Council of Trent was very important for a long time.

| Top - 0-9 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z |

Early Life and Family Background

Pallavicino was born in Rome on November 28, 1607. He was the first son of Marquis Alessandro Pallavicino. His mother was Francesca Sforza di Santa Fiora.

His family was part of the noble Pallavicini family from Parma. He was named Francesco Maria Sforza. The name Sforza honored a famous Italian general, Sforza Pallavicino. This general had adopted Francesco's father, Alessandro.

Even though he was the oldest son, Francesco chose to become a priest. This meant he gave up his right to inherit his family's wealth and titles.

Education and Early Career

Pallavicino studied many subjects at the Roman College. These included literature, philosophy, and jurisprudence (law). He earned his doctorate in philosophy in 1625 when he was just eighteen.

His first philosophy book, De Universa philosophia, was printed that same year. He then studied theology at the same college. He earned his theology doctorate in 1628.

Young Pallavicino quickly became known in Rome's cultural scene. He joined the Accademia degli Umoristi. He became friends with famous writers and thinkers of the Italian Baroque period.

He was a strong supporter of Galileo. In 1629, Pallavicino became a member of the Accademia dei Lincei. This was a famous scientific academy. He worked to challenge the old ideas of Aristotelianism.

In 1630, he became a minor priest. Soon after, Pope Urban VIII gave him important roles in the Church. He was given a pension, which was like a regular payment.

However, when his friend Giovanni Ciampoli lost favor with the Pope, Pallavicino's position was also affected. In 1632, he was sent to govern towns outside Rome. Unlike Ciampoli, Pallavicino was able to return to Rome in 1636.

Against his father's wishes, he joined the Society of Jesus (the Jesuit order) in 1637. After two years, he became a philosophy professor at the Roman College. In 1643, he became a theology professor. He held this job until 1651. He also worked for Pope Innocent X.

He was part of a group that reviewed writings by Cornelius Jansen. Pallavicino strongly disagreed with Jansenism. He supported the Jesuit way of thinking about theology.

Becoming a Cardinal

Pope Alexander VII secretly made Pallavicino a cardinal in 1657. This was made public in March 1650. He officially became a cardinal on December 6, 1660. He was given the title of San Salvatore in Lauro.

He was also appointed to examine bishops. Soon after, he joined the Congregation of the Holy Office. This was a very important group in the Church.

Pallavicino was also in charge of the Jesuit novitiate (a training house for new Jesuits). He helped plan the church of Sant'Andrea al Quirinale. This church was designed by the famous artist Gian Lorenzo Bernini.

In his later years, Pallavicino was very active in Italian culture. He joined a group of poets around Pope Alexander VII. He also supported the Accademia del Cimento, a scientific academy. He helped edit their main publication, Saggi di naturali esperienze.

In 1665, he joined the Accademia della Crusca. This group focused on the Italian language. The cardinal was a loyal supporter of Bernini. He also mentored Bernini's oldest son. A drawing of Pallavicino by Bernini is at the Yale University Art Gallery.

Pallavicino was not well enough to attend the election of the new Pope in 1667. He died in his room at the Jesuit house on June 5, 1667, at age 59. He was buried in the church of Sant'Andrea al Quirinale. His tomb was designed by the architect Mattia de Rossi.

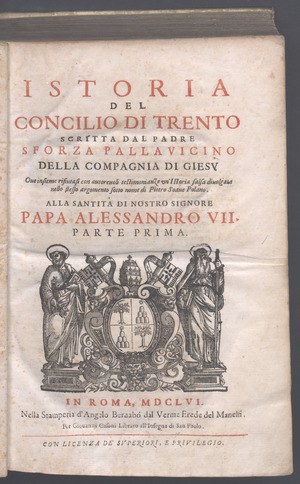

History of the Council of Trent

Pallavicino is best known for his book, History of the Council of Trent. This book was a strong response to another history written by Paolo Sarpi. Sarpi's book had been very critical of the Council.

Pallavicino's work was published in Rome in 1656 and 1657. Several people had been considered for the difficult job of correcting Sarpi's damaging book. Pallavicino took over the task in 1652.

He had access to original documents from the Council of Trent. These were kept in the Vatican archives. He also used research collected by others. Pallavicino carefully studied many historical authors.

Thanks to his own research and the work of others, he could use many printed and unpublished documents. His friend Fabio Chigi, who later became Pope Alexander VII, gave him full access to these important papers.

Pallavicino's History showed where Sarpi's book was biased or inaccurate. It was a big step forward in using original documents for historical research. A famous historian, Leopold von Ranke, said that Pallavicino's extracts from official documents were "scrupulously exact."

Until the 20th century, Pallavicino's History of the Council of Trent was the main book about this important Church meeting. Even Protestant scholars respected it. The book was translated into many languages, including Latin, French, Spanish, and German.

The original manuscript Pallavicino used is kept in the Archives of the Pontifical Gregorian University.

Other Important Works

Literary Creations

Before joining the Jesuits, Pallavicino published speeches and poems. His long poem I fasti sacri was never finished. It was meant to celebrate Christian feast days.

His first major literary work as a Jesuit was a tragedy called Ermenegildo martire. This play was a great example of Jesuit drama from the 17th century. It was published in 1644 after being performed several times.

The play tells the story of St. Hermenegild. He converted to Catholicism and rebelled against his father, an Arian king. His defeat and death were seen as a martyrdom in the fight against Arianism.

Pallavicino wrote about his ideas on theatre in a note after the play. He believed theatre should teach and provide good examples. He thought the story of a play was most important. He did not like special effects or supernatural events that made the story less believable.

He believed that plays should be realistic. He thought that good taste and classic rules could make an audience feel wonder. He disagreed with writers who thought fancy style could make up for a lack of realism.

Theological and Philosophical Writings

In 1649, Pallavicino started publishing his big work on dogma, Assertiones theologicae. This work covered all areas of dogma in nine books. He also published discussions on the Summa Theologica by Thomas Aquinas.

Pallavicino tried to connect the ideas of Aristotle with new scientific discoveries. Even though he was a Christian Aristotelian, he called himself a follower of Galileo. He also respected Tommaso Campanella. He supported Cartesian dualism, which is the idea that the mind and body are separate.

In 1649, Pallavicino published Vindicationes Societatis Jesu. This book defended the Jesuit order against many accusations. It also shared his ideas for the ideal intellectual environment within the Society of Jesus.

He argued that Jesuits didn't need to strictly follow Aristotelian ideas in all areas of natural philosophy. This was because many of Aristotle's ideas had been proven wrong. He thought it was "ridiculous" to stop discussions about new questions.

Today, Pallavicino is not as well-known outside of academic circles. However, some see him as a link between older theological ideas and modern philosophy.

He also helped publish the works of his friend Giovanni Ciampoli after Ciampoli's death. This was an effort to improve his friend's reputation. In 1665, he published an ascetic work called Arte della perfezione cristiana.

His book Trattato dello stile e del dialogo (A treatise on style and dialogue) was first published in 1646. In it, Pallavicino supported the idea of dialogue as a pleasant way to learn.

Pallavicino's book Del bene libri quattro (On the Good, four books) was praised by the Italian philosopher Benedetto Croce. Croce said it helped develop modern aesthetics (the study of beauty). Leibniz, a famous philosopher, admired this book. He wished he could have met Pallavicino.

Works Published After His Death

Some of Pallavicino's works were published after he died. Others are still in manuscript form. A writing he did about whether the Pope should live in Rome was published in 1776.

Larger collections of his works were published in the 19th century. His biography of Pope Alexander VII, which he wrote with the Pope's help, was published in 1839–40. It was called Della vita di Alessandro VII.

Letters and Connections

After Pallavicino's death, his former secretary published a collection of his letters in 1668. More collections appeared later. His letters show he had many important friends and connections. These included Fabio Chigi (who became Pope Alexander VII) and Philip IV's historian.

His Lasting Impact

Pallavicino's life was first written about by Ireneo Affò in the 18th century. Much of what we know about him comes from this biography. Later, Pietro Giordani praised Pallavicino's writing style. He compared him to other important writers of his time.

Benedetto Croce, a historian of aesthetics, saw Pallavicino as a key literary thinker of the 17th century. He believed Pallavicino's writings showed new ideas about art. Eugenio Garin, another leading historian, called him "one of the more lucid minds of the seventeenth century."

When scholars looked at Italian Baroque literature again, Pallavicino's work became important. He was seen as a leader of the "moderate baroque" style. This style tried to combine new literary ideas with a more reasoned and religious approach. Pallavicino avoided the extreme styles of his time. He preferred a balanced approach, similar to the ancient writer Cicero.

Selected Works

- Assertiones theologicæ. Rome. 1649-1652;

- Della vita di Alessandro VII. 2 vols. Prato: Giachetti. 1839-1840.

Important collections of his Complete Works include: Rome, 1834 (2 volumes); Rome, 1844-48 (33 volumes); and a collection of other works in five volumes published by Ottavio Gigli.

Works in English

- Pallavicino, Sforza. Martyr Hermenegild. Edited and translated by Stefano Muneroni. Toronto: Centre for Reformation and Renaissance Studies, 2019.

See also

In Spanish: Pietro Sforza Pallavicino para niños

In Spanish: Pietro Sforza Pallavicino para niños

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |