Rolls Series facts for kids

The Chronicles and Memorials of Great Britain and Ireland during the Middle Ages, also known as the Rolls Series, is a huge collection of historical books. These books are about British and Irish history from the Middle Ages. They were published between 1858 and 1911. There are 99 different works in 253 volumes!

Many important medieval English history books, called chronicles, were included. Older versions of these books were not very good. The series also included stories, folklore, and lives of saints (called hagiographies). Old records and legal papers were part of it too. The government paid for the series. Its nickname, "Rolls Series," comes from the fact that the books were published "by the authority of Her Majesty's Treasury, under the direction of the Master of the Rolls." The Master of the Rolls was in charge of important government records.

Contents

How the Project Started

The British Government started this project in 1857. It was based on a plan from Sir John Romilly, who was the Master of the Rolls at the time. Before this, there was another similar project called the Monumenta Historica Britannica. But it failed after only one very large book was published in 1848. Its main editor, Henry Petrie, had died. Also, the book was too big and hard to use.

Joseph Stevenson suggested starting the project again. This led to the 1857 plan. Besides Romilly and Stevenson, Thomas Duffus Hardy was also very important. He was the Deputy Keeper of the Public Records from 1861 to 1878.

The first two books came out in February 1858. One was the first part of Stevenson's own book, the Historia Ecclesie Abbendonensis. This was a history written in the 12th century at Abingdon Abbey. The other was F. C. Hingeston's book about John Capgrave's Historia de Illustribus Henricis. Hingeston's work was done carelessly, and people didn't like it much.

Editors and Their Work

Some editors produced many good books for the series. These included William Stubbs (19 volumes), H. R. Luard (17 volumes), and H. T. Riley (15 volumes). Editors were paid well for their work. For example, Stubbs earned about £6,600 over the years.

Even though many books were high quality, there wasn't much checking of the work. Slow editors also had little reason to finish their books quickly. Because of this, some books were not as good. Some people even thought the project was an easy way to make money without much effort.

At first, Romilly wanted to print 1,500 copies of each book. But this was too many, as they didn't sell that well. So, they usually printed 750 copies. Each book cost 8 shillings and 6 pence at first, which later went up to 10 shillings. (A shilling and a penny were old British money units.)

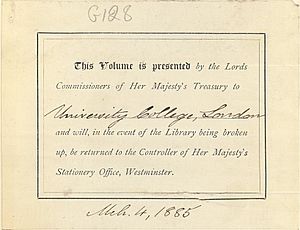

They usually sold just over 200 copies of each book. This left many extra books. So, in the 1880s, William Hardy started giving free copies to good public and university libraries. These books had a special label. It said that if the library ever closed, the book should be returned to the government office.

Ending the Project

Funding for the project started to decrease in the mid-1880s. This happened especially after Henry Maxwell Lyte became Deputy Keeper in 1886. He was worried about the quality of the books and how fast they were being made. He also thought too much money was being paid to editors who weren't doing much. He felt his office should focus on other things.

After that, work continued on books already started, but few new ones were begun. One of the last works was a 13th-century legal collection called the Red Book of the Exchequer. Hubert Hall edited it, and it came out in three books in 1897.

This book caused a very strong and angry disagreement between Hall and J. Horace Round. Round had been a co-editor but left because he was sick. He later argued with Hall. Round said Hall's book was full of mistakes and would mislead students forever. He called it "probably the most misleading publication in the whole range of the Rolls series."

The very last book to be asked for was Memoranda de Parliamento. This book contained records of a parliament meeting in Westminster in 1305. Frederic William Maitland edited it, and it came out in 1893. The final book to be printed was the second part of the Year Book for the 20th year of Edward III (1346–7). L. O. Pike edited it, and it was published in 1911.

What Was Included?

The Rolls Series included many different types of historical writings:

- Chronicles: These were historical accounts written in order of time. Examples include the Chronica Majora by Matthew Paris, edited by Henry Richards Luard. Other chronicles were by Roger of Hoveden, Benedict of Peterborough, and Ralph de Diceto, edited by William Stubbs. The works of Giraldus Cambrensis were edited by John Sherren Brewer.

- Legendary Stories: The series also had stories that were more like legends. These included tales about Ireland and Scotland, such as The Tripartite Life of St. Patrick, edited by Whitley Stokes. Icelandic sagas were also included.

- Rhymed Chronicles: Some histories were written as poems. Examples are those by Robert of Gloucester and Robert of Brunne in English, and Pierre de Langtoft in French.

- Other Works: It also had philosophical works by people like Roger Bacon. There were even books about folklore and old medicine, like Leechdoms, Wortcunning and Starcraft from Anglo-Saxon times.

- Official Records: Important archival records and legal papers were part of the series. These included the Year Books from the time of Edward I and Edward III. Other examples are the Black Book of the Admiralty and the Red Book of the Exchequer.

- Lives of Saints: Books about the lives of saints, called hagiographies, were also included. These told stories about saints like St Dunstan, St Edward the Confessor, and St Thomas Becket.

How the Books Were Made

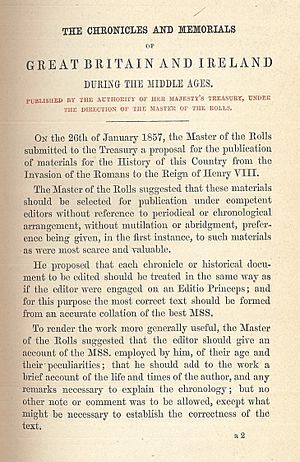

The plan for the series had clear rules for how the books should be edited:

- Focus on Rare Materials: Editors should first choose historical materials that were hard to find and very valuable.

- Careful Editing: Each history book should be edited as if it were the very first time it was being published.

- Introductions: Each book needed a short introduction. This introduction would tell about the life of the author and describe the old handwritten copies (manuscripts) that were used.

Most of the texts were in Latin. These were printed without translation. Shorthand notes from the original texts were written out fully. Texts in other old languages like Old French, Old English, Irish, Gaelic, and Welsh had translations next to them.

The books were printed in a size called octavo, which is a common book size.

Later Reprints

Many of the Rolls Series books were reprinted later. This happened in the 1960s and 1970s. The Kraus Reprint Corporation in New York reprinted them with permission.

How the Books Were Organized

The books in the series were not given numbers in order. However, the different parts of books that had many volumes were numbered. This caused some problems for librarians and people who study books. So, how the books are listed or arranged in libraries can be different. But many libraries use an unofficial numbering system, from 1 to 99. This system was used by the government office that published the books.

See also

- Record Commission

- Text publication society

- Knighton's Chronicon

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |