Ruhr pocket facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Ruhr pocket |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Western Allied invasion of Germany in the Western Front of the European theatre of World War II | |||||||

An American soldier at Rheinwiesenlager guards a massive crowd of German prisoners captured in the Ruhr pocket |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

(German resistance) |

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1,500 killed 8,000 wounded 500 missing Total: 10,000 |

317,000 captured About 10,000 dead (including prisoners of war in German captivity, foreign forced laborers, Volkssturm militia and unarmed civilians) | ||||||

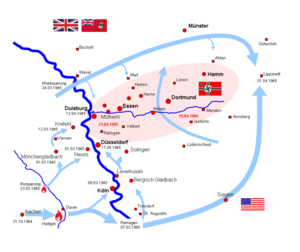

The Ruhr pocket was a major battle that happened in April 1945. It took place on the Western Front in Germany, near the end of World War II. This battle was an encirclement, meaning a large group of German soldiers was completely surrounded by Allied forces.

About 317,000 German soldiers were captured, along with 24 generals. The American forces had about 10,000 casualties, which included 2,000 soldiers killed or missing.

The battle started after the U.S. 12th Army Group, led by General Omar Bradley, quickly moved into Germany. This happened after they captured the Ludendorff Bridge at Remagen on March 7, 1945. To the north, the Allied 21st Army Group, led by Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, crossed the River Rhine on March 23 in an action called Operation Plunder.

The leading parts of these two Allied army groups met on April 1, 1945, east of the Ruhr Area. This meeting completed the encirclement, trapping 317,000 German troops to their west. While most U.S. forces moved east towards the Elbe river, 18 U.S. divisions stayed behind. Their job was to defeat the trapped German forces, known as Army Group B.

The effort to reduce the German pocket began on April 1 with the U.S. Ninth Army. The U.S. First Army joined them on April 4. For 13 days, the German forces tried to stop or slow down the U.S. advance. On April 14, the First and Ninth armies met, splitting the German pocket in half. After this, German resistance quickly fell apart.

The German 15th Army lost contact with its units and surrendered on the same day. Their commander, Walter Model, decided to break up his army group on April 15. He told the Volkssturm (a German militia) and non-fighting staff to take off their uniforms and go home. By April 16, most German forces began to surrender in large groups to the U.S. divisions. Organized fighting ended on April 18. Model, unwilling to be captured as a field marshal, took his own life on April 21.

Contents

The Start of the Battle

After D-Day in June 1944, the Allied forces began pushing east into Germany. By March 1945, the Allies had crossed the River Rhine. South of the Ruhr region, the U.S. 12th Army Group, led by General Omar Nelson Bradley, chased the weakening German armies.

They captured the Ludendorff Bridge over the Rhine at Remagen on March 7, 1945. This was a big win for the 9th Armored Division of the U.S. First Army. General Bradley and his officers quickly used this crossing to expand their bridgehead (a secure area on the enemy side of a river). The bridge later collapsed 10 days later.

North of the Ruhr, on March 23, 1945, the British Empire's 21st Army Group launched Operation Plunder. This group included the U.S. Ninth Army. They crossed the Rhine at Rees and Wesel, with air support from Operation Varsity.

How the Allies Surrounded the Germans

Forming the Encirclement

Once they crossed the Rhine, both Allied army groups spread out into Germany. In the south, the Third Army moved east. The First Army headed northeast, forming the southern part of a pincer movement around the Ruhr. In the north, the Ninth Army moved southeast, forming the northern pincer. The rest of the 21st Army Group went east and northeast.

Even before the encirclement was complete, Allied actions against the Ruhr greatly hurt Germany's economy. On March 26, Joseph Goebbels, a German official, wrote in his diary that no more coal was coming from the Ruhr.

The German forces facing the Allies were the remains of their army, some SS training units, and many Volkssturm (older men, including World War I veterans). There were also Hitlerjugend (Hitler Youth) units, made up of boys as young as 12. Many support staff and anti-aircraft gun crews were also present.

The leading parts of the two Allied pincers met on April 1, 1945, near Lippstadt. By April 4, the encirclement was complete. The Ninth Army then returned to the command of the 12th Army Group. Inside the Ruhr pocket, about 370,000 German soldiers were trapped. These included 14 divisions of Army Group B and two corps from the First Parachute Army. Millions of civilians were also trapped in cities already heavily damaged by Allied bombings.

Only about 20% of the German soldiers (75,000) had infantry weapons. Another 75,000 only had pistols. They had very little ammunition and fuel. German commander Model asked for supplies to be flown in, but Adolf Hitler refused. Hitler also denied Model's requests to retreat or break out. Hitler wanted "Fortress Ruhr" to hold out for months. However, Model's staff knew they only had enough food for three weeks, because they also had to feed millions of civilians.

Reducing the Pocket

While the main Allied operations moved east into central Germany, parts of three U.S. armies focused on the Ruhr pocket. They took it section by section. Model's troops fought strongly along the Dortmund–Ems Canal and the Sieg river. They held their ground from April 4 to April 9. They even launched a counterattack near Dortmund against U.S. 75th and 95th divisions.

For every German city that surrendered, another continued to fight for every building. Mayors of some German cities, like Duisburg and Essen, showed white flags to the U.S. troops. But German troops in Dortmund, Wuppertal, and Hamm fought fiercely for days until they were completely exhausted. The presence of SS troops often meant there would be strong resistance.

In the south, the attack by the U.S. III Corps and XVIII Airborne Corps on April 5 and 6 was slowed down. German troops cleverly used the hilly, forested Sauerland area. This forced the Americans to fight for every stream, wood, and town. The Germans fought hard for the city of Siegen. They wanted to stop the Americans from reaching open ground. The Germans were greatly outnumbered and outgunned. They could only delay the enemy, who advanced about 10 kilometers per day.

By April 11, German fighting strength was very low. They were only defending roadblocks and towns along main roads. They had a few tanks, assault guns, or 2 cm anti-aircraft guns for support. At one point, the Germans covered a valley in thick smoke. This delayed the 7th Armored Division for some time.

Throughout the battle, U.S. generals in the south did not use their two armored divisions well. They tried to send them against the Germans at every chance. But poor command decisions kept them stuck behind the U.S. infantry divisions for most of the battle.

The 13th Armored Division had a particularly difficult time. After two long marches totaling 400 kilometers, one of its combat units lost half of its Sherman tanks by the time it reached the battle area. The division was very tired. On April 10, the commander of the XVII Airborne Corps, Matthew Ridgway, ordered it into action. He was pressured by army commander Courtney H. Hodges to speed up operations. Ridgway told the division to surround and "destroy" the German forces.

The division commander, John B. Wogan, and his officers took this order literally. Communication between their units quickly broke down. The division was stopped by a stream when it tried to "destroy" the Germans. It failed to reach its goals on time and was passed by U.S. infantry divisions. Wogan was badly wounded by German rifle fire near a roadblock and was replaced by John Millikin.

On April 7, the skies cleared. The IX and XXIX tactical air commands began to attack the remaining German defenders. They shot at and bombed German troop groups and vehicle columns. The Allies wanted to capture German railway equipment. U.S. pilots were not allowed to hit this target, which limited some bombing operations. The U.S. artillery had more ammunition. Artillery supporting XVI Corps fired 259,061 rounds in 14 days.

German Surrender

On April 10, the U.S. Ninth Army captured Essen. On April 14, the U.S. First and Ninth armies met on the Ruhr river at Hattingen. This split the pocket into two parts. The smaller, eastern part surrendered the next day. Model lost contact with most of his units and commanders on April 14. The German 15th Army, led by Gustav-Adolf von Zangen, surrendered on April 14. It had lost all control over its units. The Germans had continued fighting in the pocket even though there was no real hope of rescue. They did this to keep 18 U.S. divisions busy.

Instead of surrendering his command, Field Marshal Model broke up Army Group B on April 15. By April 7, the American advance into central Germany had already made any breakout impossible. Model's chief of staff, Carl Wagener, urged him to save the lives of German soldiers and civilians by surrendering. Model refused, knowing Hitler would not allow it. He also felt he could not surrender given his demands on his soldiers throughout the war. But he also wanted to save as many lives as possible for after the war. He ordered that all young and older men be released from the army. By April 17, ammunition would be gone, so non-fighting troops could surrender that day. All fighting troops were told to either try to break out or drop their weapons and go home, which meant they could surrender.

Even before this order was fully sent out, German resistance completely collapsed on April 16. The remaining German divisions and corps surrendered in large numbers. 5th Panzer Army commander Josef Harpe was captured by paratroopers on April 17. He was trying to cross the Rhine to German forces in the Netherlands. The commander of the Allied XVIII Airborne Corps, Matthew Ridgway, sent an aide with a white flag to Army Group B's headquarters. He asked Model to surrender, but the field marshal refused, citing his oath to Hitler. When a German unit leader asked for instructions, Model told them to go home, as their fight was over. He shook their hands and wished them luck.

The western part of the pocket continued weak resistance until April 18. Model tried to reach the Harz mountains through the American lines with a small group, but he could not. Rather than surrender, he took his own life.

German anti-Nazi groups in Düsseldorf tried to surrender the city to the Allied armies. This was called "Aktion Rheinland". They wanted to save Düsseldorf from more destruction. However, SS units stopped the resistance and sadly killed many of those involved. There had already been sad events where people were harmed by the Gestapo since February. The resistance did help stop further bombings on the city by 800 bombers, by contacting the Americans. Düsseldorf was captured by Americans on April 17 without much fighting.

What Happened After

Casualties and Prisoners

The 317,000 German soldiers from the Ruhr pocket, and some civilians, were held in temporary prison camps called Rheinwiesenlager (Rhine meadow camps) near Remagen.

The Americans had about 10,000 casualties while clearing the pocket. The Ninth Army lost 341 killed, 121 missing, and just under 2,000 wounded. The First Army lost three times more, bringing the total U.S. casualties to 10,000. The divisions of III Corps lost 291 killed, 88 missing, and 1,356 wounded. The 8th Division of the XVIII Airborne Corps lost 198 killed, 101 missing, and 1,238 wounded.

The Americans freed hundreds of thousands of hungry, sick, and weak prisoners of war and forced laborers. Many of the prisoners were Red Army soldiers who were very happy to be free. The freed laborers sometimes took things and caused problems for the German population. They also crowded the roads in front of the U.S. columns. The German civilians could not believe Germany had lost the war.

The Americans also saw the huge destruction in Ruhr cities and towns from Allied bombing campaigns. In many cities, the U.S. troops found nothing but rubble, block after block. However, most of the German industrial machines, which were in protected or spread-out places, had survived. They were unharmed or only needed small repairs. This equipment was quickly made ready to use after it was captured.

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |