Schola Medica Salernitana facts for kids

The Salerno Medical School (called Schola Medica Salernitana in Latin) was a very important medical school in the Middle Ages. It was the first and most famous of its kind. Located by the Tyrrhenian Sea in the city of Salerno, in southern Italy, it started in the 9th century. By the 10th century, it became the main place for medical learning in Western Europe.

Many medical books from the Arab world, including translations of Greek texts, were kept in the library of Montecassino. These books were translated into Latin. This helped the school combine the ancient knowledge of Hippocrates, Galen, and Dioscorides with new ideas from Islamic medicine. Doctors in Salerno, both men and women, became very skilled in practical medicine. They learned a lot from their connections with Sicily and North Africa.

Contents

A Look at the School's History

The school began in the 9th century, possibly in a monastery's medicine room. It became most famous between the 10th and 13th centuries. Its reputation grew beyond Salerno during the time of the Lombards.

A key moment was when Constantine the African arrived in Salerno in 1077. He helped translate many important medical texts from Arabic. Because of his work and the support of Alfano I, Archbishop of Salerno, Salerno became known as the "Town of Hippocrates". People from all over came to the "Schola Salerni." They came hoping to get better or to learn about medicine.

The school blended ideas from Greek and Latin traditions with knowledge from Arab and Jewish cultures. It focused on preventing illness rather than just curing it. This way of thinking helped start the use of scientific methods in medicine.

The School's Founding Story

There is a famous legend about how the school started. It says that a Greek traveler named Pontus found shelter from a storm in Salerno. He was under the arches of an aqueduct. Another traveler, an Italian named Salernus, joined him. Salernus was hurt, and Pontus watched him treat his wound.

Soon, two more travelers arrived: Helinus, who was Jewish, and Abdela, who was Arab. They also showed interest in the wound. It turned out all four men were doctors! They decided to work together. They created a school to share and spread their medical knowledge.

Early Years: 9th to 10th Centuries

The Salerno Medical School likely started in the 9th century. However, there are not many records from this early time. We do not know much about the doctors or if the school was officially organized.

One story from a chronicle tells of a young woman named Theodonanda who became very ill. Her family took her to Salerno to be treated by a great doctor named Hyerolamus. He used many books to help her.

By the 10th century, Salerno was well-known for its healthy climate and its doctors. The school's fame reached northern Europe. Doctors from Salerno were known for their practical skills and experience. They often relied on what they observed and learned from practice. This was sometimes more important than old books.

In 988, a bishop named Adalbero II of Verdun traveled to Salerno to be cured. Another writer, Richerus, mentioned a Salerno doctor at the French court in 947. He noted that this doctor's knowledge came from experience, not just books.

Growth and Influence: 11th to 13th Centuries

Salerno's location as a port city helped the school grow. It brought together ideas from Arab and Eastern Roman cultures. Books by famous Arab scholars like Avicenna and Averroes arrived by sea.

Constantine the African, a doctor from Carthage, came to Salerno. He translated many important Arabic medical texts into Latin. These included works by Hippocrates, Galen, and others. Thanks to this, forgotten classical works were rediscovered. Medicine became one of the first sciences to move out of monasteries. It began to focus more on real-world practice.

Monks from Salerno and the nearby Badia di Cava monastery also played a big role. Important figures like Pope Gregory VII were connected to the city.

The school became a major center for both sick people and students from all over Europe. Many old writings in European libraries show how respected Salerno doctors were.

In 1231, Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor, officially recognized the school's importance. He declared that only doctors with a diploma from the Salerno Medical School could practice medicine. Later, in 1280, Charles II of Naples approved a law that made the school an official center for medical studies.

The school's fame spread far and wide. It kept the ancient Greek and Latin medical traditions alive. It also combined them with Arab and Jewish medical knowledge. This mix of cultures led to new ideas in medicine. A legend says the school was founded by four masters: Helinus (Jewish), Pontus (Greek), Abdela (Arab), and Salernus (Latin).

Besides medicine, the school also taught philosophy, theology, and law. Some people even consider it the first university ever founded.

One of the most famous female doctors from the school was Trota of Salerno, also known as Trotula de Ruggiero. She wrote several books on women's health and beauty. Her book De Passionibus Mulierum Curandorum was published around 1100 AD. It was a very important text for a long time. Other women doctors from this school were called the "Women of Salerno". They included Abella, Constance Calenda, Rebecca de Guarna, and Mercuriade.

The books produced by the school made it famous. One key book was the Pantegni. This was Constantine's translation of a major Arabic medical text. It had ten volumes on medical theory and ten on practical medicine. The school also produced the Antidotarium Nicolai, a famous book of medicines.

Later Years: 14th to 19th Centuries

The Salerno Medical School started to lose its importance when the University of Naples was founded. Over time, newer universities like Montpellier, Padua, and Bologna became more famous.

However, the Salerno institution continued for several centuries. It was finally closed on November 29, 1811, by Gioacchino Murat. This happened during a time when public education was being reorganized in the Kingdom of Naples. The last location of the school was the Palazzo Copeta.

The remaining doctors from the Salerno Medical School worked in Salerno's "National Convitto Tasso" for 50 years. They closed in 1861, by order of Francesco De Sanctis. He was the minister of public instruction for the new Kingdom of Italy.

How Medical Studies Worked

The school's study plan included three years of logic. Then, students studied medicine for five years, which covered surgery and anatomy. After that, they spent a year practicing with an experienced doctor. Every five years, there was also a planned autopsy of a human body.

Lessons involved explaining old medical texts. But Salerno also developed new surgical techniques. Surgery became a true science thanks to Ruggiero di Fugaldo. He wrote the first national book on surgery, which spread across Europe.

The "School" taught medicine, and women were allowed to be both teachers and students. It also taught philosophy, theology, and law. This is why some people think it was the first university.

Teachers at the Salerno Medical School divided medicine into theory and practice. Theory taught about body structures and their qualities. Practice taught how to stay healthy and fight diseases. Like other medical schools of that time, the teaching was based on the ideas of Hippocrates and Galen.

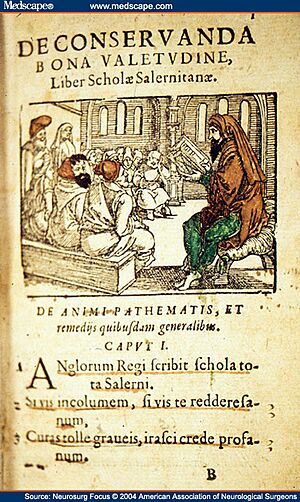

The school's most famous book is Regimen sanitatis Salernitanum. This work, written in Latin poetry, is a collection of health rules.

The Salerno Medical College

The Medical College was a separate part of the school. Its job was to test students who had finished their studies. If they passed, they received a doctorate. This allowed them to practice medicine and also to teach it.

The college also worked to protect the interests and respect of doctors. It helped stop people from practicing medicine without proper training.

The first official recognition of the college's power came from Emperor Frederick II in 1200. All doctors in the city were considered "Alunni" (alumni). They gradually gained the right to join the college. Graduation ceremonies often took place in churches or chapels.

Doctors took an oath to help the poor without asking for money. They also promised to live an honest and strict life. To get a pharmacy license, a candidate had to be moral and honest. These qualities were highly valued by the school. Diplomas often showed the year of the Pope's rule. This was because civil calendars varied, but the papal date was consistent. Diplomas always had the college's wax seal. The seal showed the city's coat of arms: Saint Matthew writing the Gospel.

Many works from Salerno have been lost. However, the school's teachers deserve credit for setting rules for doctors. These rules showed how dedicated they were to their mission. They also showed their deep understanding of the human body.

Famous Teachers at the School

There were two types of doctors: medicus and medicus et clericus. A medicus was a traditional doctor who used practical experience. A medicus et clericus was a scholar of medicine.

With Garioponto, who studied ancient Latin writers like Hippocrates and Galen, Salerno medicine began its golden age. We see for the first time a woman, the famous Trotula de Ruggiero, teaching. She gave instructions to women during childbirth.

In the early 1000s AD, Salerno had a well-organized school. Its founders were doctors who set up the school on the "Bonae diei" hill. They left behind the Flos Medicinae, a great medical work.

Teaching medicine in Salerno was done by private professors. The school was an independent organization with special teachers. The "Praeses" was in charge. Later, the "Prior" became the highest position in the college.

The medical ideas spread by Garioponto and others continued through new teachers. In the second half of the 12th century, three important teachers were Master Salerno, Matteo Plateario junior, and Musandino. Master Salerno wrote books on general therapy and making medicines. Matteo Plateario junior described plants and medical products. Musandino was known for spreading medical ideas.

Other notable figures included Romualdo Guarna, who treated William I of Sicily. Antonio Solimena treated Queen Joanna II of Naples in the late 14th century. He was also a high-ranking official. Another important person was Giovanni da Procida. Many Salerno teachers also served in armies during wars.

List of Famous Professors

- Garioponto (10–11th century)

- Peter Cleric (10–11th century)

- Alfano I (11th century)

- Constantine the African (11th century)

- Trota de Ruggiero (11th century, one of the most famous "Women of Salerno")

- Pietro da Eboli (11th century)

- Giovanni Afflacio

- Nicolò Salernitano (12th century)

- Saladino d'Ascoli (12th century)

- Giovanni Plateario, husband of Trota and his children:

- Giovanni Plateario the Young and Matte Plateary (12th century)

- Niccolò da Reggio (Nicola Deoprepio – 13th century)

- Ruggero Frugardi (13th century)

- Giovanni da Procida (13th century)

- Abella (14th century, one of the "Women of Salerno")

- Matteo Silvatico (14th century)

- Mercuriade (14th century, probably a pen name, one of the "Women of Salerno")

- Constance Calenda (15th century, one of the "Women of Salerno")

- Rebecca de Guarna (15th century, one of the "Women of Salerno")

- Vincenzo Braca (16–17th century)

- Domenico Cotugno (18th–19th century)

- Giuseppe Gaimari (18–19th century)

See also

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |