Scioto Company facts for kids

The Scioto Company was a business group that tricked people into buying land in the United States. They sold land that they did not own. An American named William Duer, who bought and sold land, was a leader of this company.

Duer worked with a British friend and several French people. They set up the company in Paris, France. They pretended to work with the Ohio Company to buy land in the Northwest Territory. However, the Scioto Company's agents sold fake land deeds to French people. These people wanted to move to the United States. Many were escaping problems from the French Revolution. The people who moved included nobles, merchants, and skilled workers. The Scioto Company never owned the land it was selling.

How the Scioto Company Started

The Scioto Land Company was created by American land buyer Colonel William Duer and others in 1787. This was after the Northwest Territory was organized. The company was officially started in 1789. It was called Compagnie du Scioto in Paris. Joel Barlow from America, William Playfair from Scotland, and six Frenchmen were involved. Playfair worked for Duer and his partners.

The Big Problem: No Land!

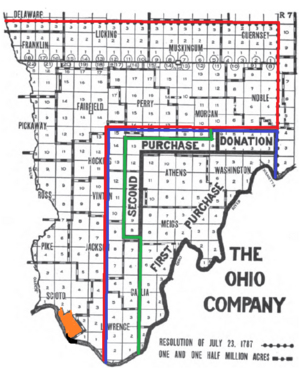

In 1787, this company made a deal with the Ohio Company. They planned to use about 4,000,000 acres (about 16,000 km2) of land. This land was north of the Ohio River and east of the Scioto River. The Ohio Company had an option to buy this land. But the people selling the land in France were dishonest. Also, Duer and his partners did not keep their agreement with the Ohio Company. Because of this, the Scioto Company failed in early 1790. Two tries to restart it also failed.

Meanwhile, about 150,000 acres (about 600 km2) had been "sold" to people and companies in France. On February 19, 1791, 218 of these buyers left Havre de Grace, France. They arrived on May 3 in Alexandria, Virginia.

These people were part of a group called the French 500. Many were leaving the troubles of the French Revolution. When they arrived, they learned that the Scioto Company owned no land. About fifty of them landed in Marietta, Ohio, along the Ohio River. In October 1791, the rest of the group went to Gallipolis. This town was being built around that time. It is now in Gallia County, Ohio. The company had built simple huts for the group. Most of these people were from cities and did not know how to live on the undeveloped frontier. The company's agent told them this land was part of their purchase. However, this land was actually part of the area bought by the Ohio Company. The Ohio Company had sold it to the Scioto Company, but took it back when the Scioto Company did not pay.

Help for the Settlers

In 1794, William Bradford, who was the U.S. Attorney General, decided something important. He said that all rights to the 4,000,000 acres (about 16,000 km2) belonged to the Ohio Company. In 1795, the Ohio Company sold the land the French settlers were living on to them. They also sold them nearby developed lots. The settlers had to pay for their land a second time.

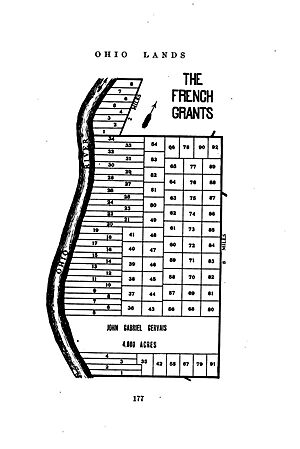

The United States government learned about their difficult situation. In 1795, the government gave the French settlers about 24,000 acres (about 97 km2) of land. This land was in the southern part of what is now Scioto County, Ohio. It had a long front along the Ohio River. This land is known as the First French Grant. Some of the settlers moved to this area. But most stayed in Gallipolis. They were committed to the land they had started to develop there. Four thousand acres of the French Grant were set aside for John Gabriel Gervais. The remaining 20,000 acres were to be divided among the other people living in Gallipolis.

Eight people living in Gallipolis somehow missed out on the 1795 land distribution. In 1798, Congress made another grant of land next to the first one. This was called the Second Grant. It was 1,200 acres (about 4.9 km2) for these eight people. Most of the French residents had already started their lives in Gallipolis. So, they never lived on either of the grants. They either sold their land or sent farmers to live on their plots.