Sharifian Solution facts for kids

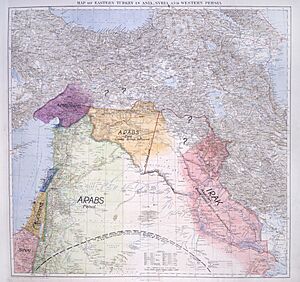

The Sharifian Solution was a plan by the British government after World War I. It aimed to set up new countries in the Middle East, which was once part of the Ottoman Empire. The main idea was to place the sons of Hussein bin Ali al-Hashimi, who was the Sharif of Mecca and King of Hejaz, as rulers of these new nations.

In 1918, T. E. Lawrence (also known as Lawrence of Arabia) first suggested this plan. He proposed that Hussein's second son, Abdullah, would rule Baghdad and southern Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq). His third son, Faisal, would rule Syria. And his fourth son, Zeid, would rule northern Mesopotamia. Hussein himself would not have political power in these new areas. His first son, Ali, would take over as ruler in Hejaz.

However, things changed. France removed Faisal from Syria in July 1920. Also, Abdullah moved into Transjordan (which was part of Faisal's planned Syria) in November 1920. Because of these events and the need to save money, the final Sharifian Solution was different. Winston Churchill, then the British Secretary of State for the Colonies, put a new policy into action after the 1921 Cairo Conference.

Under this new plan, Faisal became the ruler of Iraq, and Abdullah became the ruler of Transjordan. Zeid did not get a role. It also became difficult to make agreements with Hussein and the Kingdom of Hejaz. The British hoped that the family ties would help them control these new states, but this idea did not work out as planned.

Later, in 1938, George Antonius wrote in his book The Arab Awakening that Lawrence's claim in Seven Pillars of Wisdom (1926) about Britain fulfilling its promises was not entirely true.

Abdullah was assassinated in 1951, but his family still rules Jordan today. The other two branches of the Hashemite dynasty did not last. Ali was removed by Ibn Saud in 1924/25 after the British stopped supporting Hussein. Faisal's grandson, Faisal II, and Ali’s son, 'Abd al-Ilah, were executed during the 1958 Iraqi coup d'état.

Contents

The Middle East After World War I

After World War I, the Ottoman Empire was broken up. Britain and France had secret agreements, like the Sykes-Picot Agreement, to divide the Middle East. This caused problems with promises Britain had made to Arab leaders, especially Hussein, in the McMahon-Hussein Correspondence. Britain also made the Balfour Declaration, which supported a Jewish homeland in Palestine. These conflicting promises created a very complicated situation.

Faisal's Role in Syria

Faisal, one of Hussein's sons, was the first to get an official role. He led the Arab-British military administration in eastern Syria, called OETA East. Arab and British armies entered Damascus on October 1, 1918. Faisal arrived on October 4 and appointed Rida Pasha al-Rikabi as his prime minister. This area included parts of modern-day Syria.

Faisal believed that the area promised to his father in the McMahon-Hussein correspondence included the "Blue Zone" that France claimed in the Sykes-Picot Agreement. On September 15, 1919, British and French leaders agreed that British forces would leave Syria by November 1. This meant OETA East became an Arab-only administration on November 26, 1919.

Faisal went to London and later Paris to discuss the future of Syria. He learned more about the promises made to his father. He felt that his father and brother Abdullah had not told him everything. In Paris, Faisal and French leader Georges Clemenceau agreed on January 6, 1920. France would allow Syria some independence with Faisal as king, but Syria would remain under French control.

When Faisal returned to Damascus on January 16, he could not convince his supporters about this agreement. On March 8, 1920, the Syrian National Congress declared Faisal King of the Arab Kingdom of Syria. This kingdom was meant to cover all of OETA East and other parts of historical Syria, including Palestine.

Both British and French leaders disapproved of this. They stopped paying a monthly subsidy to Faisal. In April 1920, the San Remo Conference gave France a Mandate (control) over Syria. Faisal was invited but did not attend.

On May 11, the new French leader, Alexandre Millerand, stated that France could not accept Faisal acting as both a representative of his father and a king under French control. Hussein himself also seemed to distance himself from Faisal's actions in Syria.

The Arab Kingdom of Syria ended on July 25, 1920, after the Franco-Syrian War and the Battle of Maysalun, where French forces defeated Faisal's army.

British Policy and Money Matters

In 1920, there were many debates in the British Parliament about policies in the Middle East. Many members of Parliament questioned whether Britain was keeping its promises to the Arabs.

Britain wanted Hussein to approve the Mandates, especially the one for Palestine. Hussein had not signed the peace treaties that established these mandates. His signature would have helped calm the political arguments in Britain about broken promises. This was important for Churchill's Sharifian Solution, which relied on the idea of a united Hashemite family.

Winston Churchill, as Secretary of State for War, had argued since 1919 that Britain should leave the Middle East. He believed it would cost too much money without enough benefit. He specifically mentioned Palestine as a venture that would "never yield any profit."

On February 14, 1921, Churchill became the head of the Colonial Office. His main task was to save money in the Middle East. He organized the Cairo Conference to achieve this and to make an agreement with the Arabs.

The Cairo and Jerusalem Meetings

The Cairo Conference was a meeting of British officials in March 1921. Key figures included Churchill, Lawrence, Percy Cox, Herbert Samuel, and Gertrude Bell. Two Iraqis, Jafar al-Askari and Sassoon Eskell, also attended. Churchill later traveled to Jerusalem for more meetings.

On June 14, 1921, Churchill reported to Parliament about the conference's results. He said, "We are leaning strongly to what I may call the Sherifian solution, both in Mesopotamia, to which the Emir Feisal is proceeding, and in Trans-Jordania, where the Emir Abdulla is now in charge." He also mentioned giving aid to King Hussein.

Standing first row: from left: Gertrude Bell, Sir Sassoon Eskell, Field Marshal Edmund Allenby, Jafar Pasha al-Askari

Meetings with Abdullah

Abdullah, another of Hussein's sons, arrived in Amman (Transjordan) on March 2, 1921. He sent a representative to Jerusalem to meet with Herbert Samuel, the British High Commissioner for Palestine. Samuel insisted that Transjordan could not be used to attack Syria.

Between March 28 and 30, Churchill met with Abdullah three times. Churchill suggested that Transjordan become an Arab province under an Arab governor, who would report to the British High Commissioner. Abdullah wanted control over all of Mandate Palestine or a union with Iraq. Churchill rejected both ideas.

Abdullah was worried about a Jewish kingdom being set up west of the Jordan River. Churchill reassured him that large numbers of Jews would not suddenly move into the area. He also said that Transjordan would not be part of the Palestine administrative system, meaning the Zionist goals of the mandate would not apply there. Hebrew would not be an official language, and the local government would not promote Jewish immigration. Herbert Samuel added that no Jewish government would be set up in Palestine, no land would be taken from Arabs, and the Muslim religion would not be harmed.

The British suggested that if Abdullah could stop Syrian nationalists from acting against the French, it might help his brother Faisal become ruler of Iraq. It might even lead to Abdullah becoming Emir of Syria. In the end, Abdullah agreed to stop his advance towards French-controlled Syria. He agreed to govern the territory east of the Jordan River for a six-month trial period, receiving a British payment of £5,000 per month.

Transjordan's New Ruler

The region that became Transjordan was separated from French-controlled Syria after the French defeated King Faisal in July 1920. For a while, this area had no clear ruler or occupying power. British officials described it as "politically derelict," meaning it was left without a proper government.

On September 7, 1920, local leaders received telegrams from Hussein. He announced that one of his sons was coming north to organize a movement against the French in Syria. Abdullah arrived in Ma'an on November 21, 1920, and then in Amman on March 2, 1921.

Abdullah officially established his government in Transjordan on April 11, 1921.

Faisal Becomes King of Iraq

Abdullah's Hopes for Iraq

On the same day Faisal was declared King of Syria, a group of Iraqis in Damascus, including Ja'far al-Askari, called for Iraq's independence. They wanted Abdullah to be king of Iraq, with Zeid as his deputy. They also hoped for Iraq to eventually unite with Syria. A few weeks later, in June 1920, the Iraqi revolt against the British began.

Faisal's Path to Iraq

After the Arab Kingdom of Syria fell, Faisal traveled to Italy. On his way, he received a letter from his father, Hussein. The letter told Faisal to only discuss policy with the British government based on the McMahon-Hussein correspondence. It also criticized Faisal for trying to create a separate kingdom instead of remaining Hussein's representative. Faisal was open to ruling Iraq, either as king or as a regent for Abdullah, if the British government wanted him there.

Faisal went to Switzerland and then to Lake Como, waiting for an invitation to England. In November, Hussein appointed Faisal to lead the Hejaz delegation in Europe. Faisal arrived in England on December 1.

Faisal in England

Faisal met with King George on December 4. He also sent messages to his father, Hussein, asking him to tell Abdullah not to threaten actions against the French, as this could harm the discussions in London.

On December 9, Lawrence of Arabia suggested to Faisal that Britain would act in Iraq. Lawrence asked Faisal for his views. Faisal's biographer noted that Faisal secretly wanted the position, even if it caused family conflict.

After getting approval from Hussein on December 19, Faisal met with British diplomats. They discussed Hussein's refusal to sign the Treaty of Sèvres. Faisal explained that Hussein would not sign until he was sure Britain would fulfill its promises. They also compared the English and Arabic versions of the McMahon-Hussein correspondence to resolve any misunderstandings.

One British official noted that the Arabic version of the correspondence made it seem like Britain could act freely in the whole area without harming France. This was problematic for the British. The official thought that the British government might use this opportunity to send Faisal to Mesopotamia (Iraq). Some historians later claimed that the Arabic document Faisal presented was not authentic.

In early January, Faisal was shown a document from 1916 that interpreted the correspondence. This was the first time an argument was made that Palestine was meant to be excluded from the Arab area.

On January 7 and 8, a British official informally asked Faisal about becoming king of Iraq. Faisal was hesitant. He said he would "never put myself forward as a candidate" and that Hussein wanted Abdullah to go to Mesopotamia. He worried people would think he was working for himself. However, he said he would go "if HMG rejected Abdullah and asked me to undertake the task and if the people said they wanted me." The official believed Faisal wanted to go to Mesopotamia but would not push himself.

On January 8, Faisal met with Lawrence and other British officials at a country house. According to memoirs, Faisal agreed to become King of Iraq after many hours of discussion. This meeting and its results were kept secret.

On January 10, Faisal met with Lawrence again. They discussed changes in the British department responsible for the Middle East. Faisal still hesitated about Iraq, preferring that Britain formally propose him. Lawrence reported to Churchill that he could not yet confirm Faisal would accept the nomination.

Faisal met with Lord Curzon, the British Foreign Secretary, on January 13. Faisal was concerned about Ibn Saud and wanted to clarify Britain's position, as another British office seemed to support Ibn Saud. Curzon believed Hussein was risking his own safety by not signing the Treaty of Versailles. Faisal asked for weapons for Hejaz and for the subsidy to be restarted, but Curzon refused.

Lawrence wrote to Churchill on January 17, 1921, saying that Faisal "had agreed to abandon all claims of his father to Palestine" in exchange for Arab rule in Iraq, Transjordan, and Syria. The exact date and content of this letter are debated by historians.

On January 20, Faisal met with several British officials. According to Faisal's biographer, this meeting led to a misunderstanding. Churchill later claimed in Parliament that Faisal had agreed that Palestine was excluded from the promises for an independent Arab Kingdom. However, the meeting minutes suggest Faisal only accepted that this was the British government's interpretation, not that he agreed with it. Churchill later confirmed in Parliament that Faisal had accepted the British interpretation of the exclusion of Palestine.

On February 3, 1921, a draft of the Mandate for Palestine was published. Faisal formally protested to Curzon on January 6, and his protest was published on February 9. He also filed a petition to the League of Nations on February 16, arguing that the situation violated wartime pledges. However, the petition was rejected.

On February 16, Faisal met Lawrence. Lawrence told him he had accepted a position in the Colonial Office's Middle Eastern Department. He spoke of a possible conference in Egypt to discuss the politics and future of Arab areas. Lawrence suggested Faisal should be hopeful for a good settlement.

On February 22, Faisal met Churchill, with Lawrence interpreting. Faisal's acceptance of the Mandate and a promise not to work against the French were not explicitly agreed upon. Faisal expressed doubts about what a Mandate would mean. Churchill told Faisal that "things might be arranged" by March 25 and that Faisal should stay in London.

On March 10, Faisal submitted a memorandum to the Conference of Allied Powers. He had written to Lloyd George on February 21, asking for a Hejazi delegation to attend. The French objected, but eventually agreed to receive a submission from Faisal's representative.

The Cairo Conference opened on March 12 and discussed Faisal becoming king of Iraq. On March 22, Lloyd George told Churchill that the Cabinet was impressed by his recommendations. They decided that Percy Cox should go to Mesopotamia to start the process for Faisal to be accepted as ruler of Iraq. Faisal would be told privately to return to Mecca to consult his father. If Faisal, with his father's and brother's consent, became a candidate and was accepted by the people of Iraq, Britain would welcome their choice. This was conditional on Faisal accepting the terms of the mandate and not working against the French.

Lawrence cabled Faisal on March 23: "Things have gone exactly as hoped. Please start for Mecca at once... I will meet you on the way and explain the details." Faisal left England in early April.

Faisal's Return Home

At Port Said on April 11, 1921, Faisal met Lawrence to discuss the Cairo Conference and the path forward. Lawrence reported to Churchill that Faisal promised to do his part and guaranteed not to attack or work against the French. Faisal still had reservations about the Mandate.

Faisal arrived in Jeddah on April 25. After discussions with Hussein in Mecca and preparing for his arrival in Iraq, he left on June 12 for Basra. He was accompanied by Iraqis who had sought refuge in Hejaz after the 1920 rebellion and were now returning as part of an amnesty. His close advisors and his new British advisor, Cornwallis, were also with him.

Faisal's Coronation

Faisal arrived in Basra on June 23, 1921. This was his first time in Iraq. Just two months later, on August 23, 1921, he was crowned King of Iraq.

Hussein and the Hejaz Kingdom

End of British Payments

Between 1916 and April 1919, Hussein received £6.5 million from Britain. In May 1919, this payment, called a subsidy, was reduced. By February 1920, no more payments were made. When Churchill took over the Colonial Office, he supported continuing the subsidies. He argued that given the savings in Iraq, £100,000 was not too much, and Hussein should even receive more than Ibn Saud. However, the Cabinet decided to limit any subsidy to £60,000, the same amount as for Ibn Saud. They also wanted Hussein to sign the peace treaties.

Hussein Refuses to Sign Treaties

In 1919, King Hussein refused to approve the Treaty of Versailles. In August 1920, after the Treaty of Sèvres was signed, Lord Curzon asked Cairo to get Hussein's signature on both treaties. He offered £30,000 if Hussein signed. Hussein refused. In February 1921, he stated he could not sign a document that gave Palestine to Zionists and Syria to foreigners.

In July 1921, Lawrence of Arabia was tasked with getting Hussein to sign a treaty and the peace treaties. A £60,000 annual payment was offered. This would have completed the "Sherifian triangle" of British influence. However, this attempt also failed. Hussein continued to refuse to recognize any of the Mandates, which he saw as part of his own domain. In 1923, another attempt to settle issues with Hussein failed. In March 1924, after Hussein declared himself Caliph, the British government stopped all negotiations.

The British and the Hajj

Mecca was important to the Muslim world, and Britain ruled a large Muslim empire. The British believed that a successful hajj (pilgrimage to Mecca) would improve Hussein's standing and, indirectly, Britain's. This led to increased attention on Mecca.

Hussein's Claim as Caliph

On March 7, 1924, four days after the Ottoman Caliphate was abolished, Hussein declared himself Caliph of all Muslims. However, Hussein's reputation had been damaged by his alliance with Britain and his rebellion against the Ottoman Empire. Also, the former Ottoman Arab region was now divided into many countries. As a result, his claim received more criticism than support in populous Muslim countries like Egypt and India.

Relations with Nejd

By late 1923, Hejaz, Iraq, and Transjordan all had border issues with Nejd, ruled by Ibn Saud. A conference began in November 1923 to resolve these issues but ended in May 1924 without success. Hussein refused to attend unless certain conditions were met, and Ibn Saud refused to send his son.

Hussein's Abdication

Under local pressure, Hussein gave up his throne on October 4, 1924. He left Jeddah for Aqaba on October 14. His son Ali took the throne but also gave it up on December 19, 1925. Ali then joined Faisal in Iraq, ending Hashemite rule in the Hejaz.

Sharifian Family Tree

Here is a family tree showing the relationships between the members of the Sharifian family:

Sharif of Mecca November 1908 – 3 October 1924 King of Hejaz October 1916 – 3 October 1924 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

King of Hejaz 3 October 1924 – 19 December 1925 (Monarchy defeated by Saudi conquest) |

Emir (later King) of Jordan 11 April 1921 – 20 July 1951 |

King of Syria 8 March 1920 – 24 July 1920 King of Iraq 23 August 1921 – 8 September 1933 |

Zeid (pretender to Iraq) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 'Abd Al-Ilah (Regent of Iraq) |

King of Jordan 20 July 1951 – 11 August 1952 |

King of Iraq 8 September 1933 – 4 April 1939 |

Ra'ad (pretender to Iraq) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

King of Jordan 11 August 1952 – 7 February 1999 |

King of Iraq 4 April 1939 – 14 July 1958 (Monarchy overthrown in coup d'état |

Zeid | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

King of Jordan 7 February 1999 – present |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hussein (Crown Prince of Jordan) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |