Smallpox vaccine facts for kids

The smallpox vaccine was the very first vaccine ever made to fight a contagious disease. In 1796, a British doctor named Edward Jenner showed that getting infected with the mild cowpox virus could protect people from the deadly smallpox virus. Cowpox worked like a natural vaccine for a long time.

Later, in the 20th century, a modern smallpox vaccine was developed. From 1958 to 1977, the World Health Organization (WHO) led a huge effort to vaccinate people around the world. This campaign successfully got rid of smallpox, making it the only human disease to be completely wiped out! Even though most people don't get the smallpox vaccine anymore, it's still made. This is to protect against things like bioterrorism and the mpox virus.

The word vaccine comes from the Latin word for cow. This reminds us of how smallpox vaccination first started. Edward Jenner called cowpox variolae vaccinae, which means "smallpox of the cow." Over time, people became less sure about where the smallpox vaccine came from. This was especially true after Louis Pasteur created new ways to make vaccines in a lab in the 1800s. In 1939, Allan Watt Downie showed that the modern smallpox vaccine was different from cowpox. Because of this, the virus in the vaccine was named vaccinia, which is now seen as its own type of virus.

Contents

How Do Smallpox Vaccines Work?

The smallpox vaccine has changed a lot over time. It is the oldest vaccine we know about. From 1796 to the 1880s, the vaccine was passed from one person to another. This was done by taking fluid from a vaccinated person's arm and putting it into another person's arm.

Starting in the 1840s, scientists learned to grow the smallpox vaccine in cattle. By the 1880s, vaccine made from calf lymph (fluid from calves) became the main type.

First-Generation Vaccines

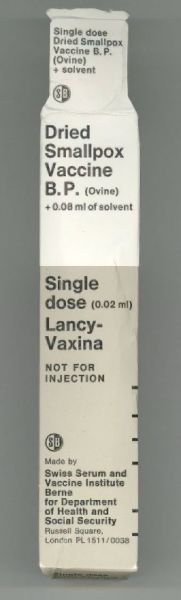

First-generation vaccines were made by growing the live vaccinia virus on the skin of animals. Most of these were calf lymph vaccines, grown on cows. But sometimes other animals, like sheep, were also used. In the 1950s, scientists developed freeze-dried vaccines. This meant the vaccinia virus could be stored for a long time without needing a refrigerator. Dryvax is an example of a freeze-dried vaccine.

These vaccines use a live, strong vaccinia virus. About one-third of people getting the vaccine for the first time might feel sick enough to miss school or work. Some children might get a fever. The vaccine spot on the skin can also spread the virus to other people. Very rarely, serious side effects can happen. Many countries still have these first-generation smallpox vaccines stored away.

Second-Generation Vaccines

Second-generation vaccines also use live vaccinia virus. But these are grown in special egg membranes or in cell cultures. This way of making vaccines helps keep them cleaner. First-generation vaccines could sometimes have skin bacteria from the animals they were grown on.

These vaccines are also given by scratching the skin with a special needle. They can have similar side effects to the first-generation vaccines. Scientists like Ernest William Goodpasture started growing vaccinia virus in chicken embryos in 1932. Later, in the 1960s, the WHO supported growing the virus in rabbit kidney cells.

ACAM2000 is a second-generation vaccine. It was made from a strain of vaccinia virus found in Dryvax. This vaccine is grown in special human cells (MRC-5 cells) and then in monkey kidney cells (Vero cells). The United States has ordered many doses of ACAM2000 for its emergency supply.

Third-Generation Vaccines

Third-generation vaccines use attenuated (weakened) vaccinia viruses. This means they are much less strong and cause fewer side effects. These weakened viruses might still be able to copy themselves, or they might not.

MVA Vaccine

Modified vaccinia Ankara (MVA) is a type of vaccinia virus that cannot copy itself in human cells. It was developed in West Germany. The original Ankara strain of vaccinia was grown in donkeys and cows. After many steps in the lab, the virus lost parts of its genetic material. This made it unable to grow in human cells. MVA was used in West Germany for a short time, but the end of smallpox stopped the vaccination program.

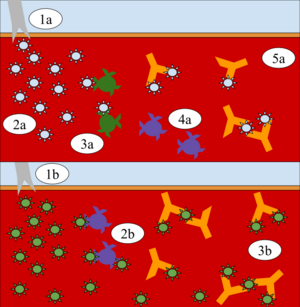

MVA causes the body to make fewer antibodies than stronger vaccines. During the smallpox eradication, MVA was thought of as a "pre-vaccine." It could be given before a stronger vaccine to reduce side effects. Or it could be a safer option for people who might have serious problems with a stronger vaccine.

MVA-BN Vaccine

MVA-BN is a vaccine made by Bavarian Nordic. It is known by different names: Imvanex in Europe, Imvamune in Canada, and Jynneos in the United States. This vaccine is given as a shot under the skin. Unlike other smallpox vaccines, it does not create a "take" or a pustule on the skin. A "take" is a blister or a hard, red area around the shot site.

MVA-BN can also be given as a shot into the skin. This helps stretch the supply of doses. It is safer for people with weak immune systems or those at risk from a strong vaccinia infection. MVA-BN is approved in many places and has been found to be safe and work well. It is also approved to protect against mpox.

LC16m8 Vaccine

LC16m8 is another weakened vaccinia vaccine. It is made in Japan. This vaccine still causes a "take" on the skin, but it is much safer than the older vaccines. LC16m8 was approved in Japan in 1975 after being tested on many children.

Is the Smallpox Vaccine Safe?

The vaccinia virus in the vaccine can spread, which helps it work. But it can cause serious problems for people with weak immune systems. This includes people getting chemotherapy or those with AIDS. It is also not safe for pregnant women. If a woman plans to get pregnant, she should not get the smallpox vaccine.

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) says that if you get the vaccine within 3 days of being exposed to the virus, it might protect you from getting sick. If you do get sick, it might be much milder. If you get the vaccine 4 to 7 days after exposure, it will likely still give you some protection.

In 2007, a group of experts in the U.S. (VRBPAC) agreed that ACAM2000 is safe and works well for people at high risk of smallpox. However, because it can have serious side effects, it is mainly kept in the U.S. national emergency supply.

Where Are Smallpox Vaccines Stored?

Since smallpox has been wiped out, most people don't get vaccinated against it anymore. The World Health Organization used to have a large supply of vaccines. But most of it was destroyed in the late 1980s when smallpox didn't come back.

After the September 11 attacks in 2001, many governments started building up vaccine supplies again. This was because of fears of bioterrorism. Companies started making smallpox vaccines again. Older vaccines from the 1950s were also found and given to governments.

Newer vaccines have expiration dates, so they need to be replaced. The United States has a large supply of ACAM2000 and MVA-BN vaccines. Older first-generation vaccines can last a very long time if kept frozen. For example, a U.S. supply of WetVax from the 1950s was still good in 2004. Also, these vaccines can still work even when diluted. This means a smaller number of doses can protect more people.

| Country, region, or organization | Year | Doses (millions) | Composition (generation) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 2.7 |

|

|

(pledged) |

2018 | 27 | Various (1st, 2nd, 3rd) |

| 2006 | 55 | 55 million Pourquier (1st) | |

| 2022 | 100 |

|

|

| 2022 | 5 | ||

| 2006 | 56 | LC16m8 (3rd) | |

| 2017 | ? | Lister/Elstree-RIVM (2nd) | |

| 2022 | 35 | Lancy-Vaxina (1st) | |

| 2022 | 185 |

|

History of Smallpox Vaccination

Early Ways to Gain Immunity

Before modern vaccines, people used a method called "variolation" to try and prevent smallpox. This involved giving someone a small amount of the smallpox virus itself. This practice likely started in Africa and China long before it came to Europe.

In China, people would blow powdered smallpox scabs up the noses of healthy people. The person would then get a mild case of smallpox. After recovering, they would be immune. This method had a death rate of about 0.5–2.0%. This was much lower than the 20–30% death rate of natural smallpox.

In the early 1700s, reports of this method reached England from places like Turkey. Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, a British ambassador's wife, saw variolation in the Ottoman Empire. In 1718, she had her five-year-old son variolated, and he recovered quickly. When she returned to London, she had her daughter variolated during a smallpox outbreak. This helped the British Royal Family become interested in the method.

In North America, variolation was first used in 1721. A preacher named Cotton Mather learned about it from Onesimus, an enslaved man who had been variolated in Africa. At first, many people criticized this practice. However, it was shown to be much safer than getting smallpox naturally.

Edward Jenner and the First Vaccine

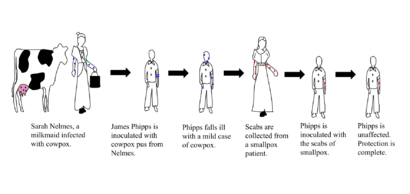

Edward Jenner was an orphan who nearly died from smallpox variolation as a child. When he was 13, he became an apprentice to a surgeon. He noticed that people who caught cowpox from working with cattle usually didn't get smallpox. Jenner thought there was a connection.

From 1770 to 1772, Jenner got more training in London. He then returned to his hometown. Other people in England and Germany had also tried using cowpox to protect against smallpox. But Jenner was the first to publish his findings and share the vaccine widely.

In 1797, Jenner sent a paper about his observations to the Royal Society. It was not accepted at first. After more vaccinations, in 1798, Jenner published his famous work. It was called An Inquiry into the Causes and Effects of the Variolae Vaccinae. He showed that cowpox vaccination was a safe way to prevent smallpox. He thought the protection would last a lifetime, but this turned out to be wrong.

The smallpox vaccine quickly spread around the world. In 1799, the first smallpox vaccine in the United States was given. By 1800, Jenner's work was known across Europe and in the U.S.

In 1804, the Balmis Expedition was a Spanish mission that took the vaccine to the Spanish Empire. They carried the live cowpox virus by vaccinating 22 orphaned boys. As they traveled, fluid from these boys was used to vaccinate local people.

Napoleon, the French leader, was a big supporter of smallpox vaccination. He ordered that his army recruits be vaccinated. By 1815, about half of French children were vaccinated. This led to a big drop in smallpox deaths in France.

Some countries made vaccination required by law. The first was a small German state in 1806. Bavaria followed in 1807, and other European countries later. In England, vaccination became required for babies in 1853. But people who disagreed fought against it, and the law was changed over time.

In the United States, each state decided its own vaccination rules. Some states made it required for children to attend school. The U.S. Supreme Court supported this in 1905, saying that public health was more important than personal freedom in this case.

How Vaccines Were Made Better

Until the late 1800s, vaccines were often made by scraping material from the skin of calves. Sometimes, the vaccine was passed from person to person. There were no good ways to check if the vaccine was safe. This meant that sometimes, other infections could be spread through the vaccine.

Sydney Arthur Monckton Copeman, an English scientist, found that adding glycerine to the vaccine helped kill many harmful bacteria. This made the vaccine much safer. In 1899, the British government started giving out this safer vaccine for free.

However, glycerinated vaccine lost its strength quickly in warm places. So, it was hard to use in tropical countries. Animals continued to be used to make vaccines for a long time.

In the 1940s and 1950s, Leslie Collier, another English scientist, developed a way to make a heat-stable, freeze-dried vaccine. He added special ingredients that protected the virus during the drying process. This dried vaccine could last for months in warm temperatures. This was a huge step forward for vaccination campaigns in hot, remote areas. Collier's method became the standard for making smallpox vaccines around the world.

A big help in smallpox vaccination came in the 1960s from Benjamin Rubin. He invented the bifurcated needle. This was a two-pronged fork designed to hold one dose of vaccine. It was easy to use, cheap, and could be reused after cleaning. It used much less vaccine than other methods. This needle was used for 200 million vaccinations each year during the last years of the WHO's smallpox eradication campaign.

Wiping Out Smallpox

Smallpox was completely wiped out thanks to a huge international effort. This campaign started in 1967 and was led by Donald Henderson and the World Health Organization (WHO). They searched for outbreaks and quickly vaccinated people in those areas.

The last natural case of smallpox in the world happened in Somalia in October 1977. In 1980, the WHO officially announced that smallpox had been eradicated. This was a massive achievement!

Even after smallpox was gone, some labs still had samples of the virus. After two accidental smallpox cases in 1978, the WHO made sure that known virus samples were either destroyed or moved to very safe labs. By 1984, the only known samples were kept in two high-security labs: one in the U.S. and one in Russia. These samples are kept for research on how to fight biological weapons and in case smallpox ever reappears naturally.

Preparing for Future Threats

After the September 11 attacks in 2001, the United States government started a program to vaccinate healthcare workers. This was to prepare for a possible bioterrorist attack using smallpox. Many healthcare workers were worried about side effects, so fewer than expected got the vaccine.

In 2022, Canada also ordered a large supply of smallpox vaccine. This was to protect against any accidental or intentional release of the virus. These vaccines were used to help control the 2022 monkeypox outbreak.

Where Did the Vaccine Come From?

For a long time, no one was sure where the modern smallpox vaccine came from. Edward Jenner got his vaccine from a cow, so he named the virus vaccinia, after the Latin word for cow. Jenner thought both cowpox and smallpox came from horses and then spread to cows. Some doctors even vaccinated people directly with horsepox.

Things got more confusing when Louis Pasteur developed lab methods for making vaccines. Scientists would grow viruses in labs, and sometimes the records weren't clear. By the late 1800s, it was unclear if the vaccine came from cowpox, horsepox, or a weakened form of smallpox.

In 1939, Allan Watt Downie showed that the vaccinia virus was different from the "natural" cowpox virus. This proved that vaccinia and cowpox are two separate types of viruses. The term vaccinia now only refers to the smallpox vaccine virus.

In the 1990s, whole genome sequencing allowed scientists to compare the genetic material of different viruses. In 2006, the horsepox virus was studied. It was found to be the closest relative to vaccinia. This suggests that the smallpox vaccine might have originally come from horsepox, not cowpox. Older smallpox vaccines have been found to be very similar to horsepox.

What Do the Words Mean?

The word "vaccine" comes from Variolae vaccinae, which means "smallpox of the cow." This was the term Edward Jenner used for cowpox. The word "vaccination" soon replaced "cowpox inoculation."

At first, "vaccine" and "vaccination" only referred to smallpox. But in 1881, Louis Pasteur suggested that these terms should be used for all new protective shots. He wanted to honor Edward Jenner for his important discovery.

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |