Solomon Ayllon facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Solomon Ayllon |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Religion | Judaism |

| Personal | |

| Born | 1665 Salonica, Ottoman Empire |

| Died | 10 April 1728 Amsterdam, Netherlands |

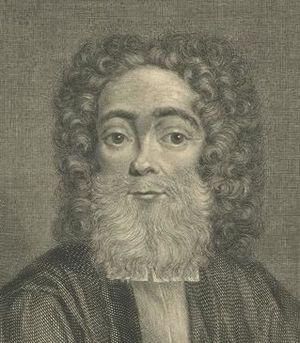

Solomon Ayllon (1665 – 10 April 1728) was an important Jewish leader. He served as a haham (a chief rabbi or wise man) for Sephardic Jewish communities in London and Amsterdam. His family name, Ayllon, comes from a town in what is now Spain.

Ayllon was not known as a great scholar or expert in the Talmud (a central text of Judaism). However, his life was closely connected to a religious movement called Sabbateanism. This movement had followers in both the East and the West.

Contents

Solomon Ayllon's Life Story

Early Years and Travels

Solomon Ayllon likely grew up in Thessaloniki (also known as Salonica), which was part of the Ottoman Empire. Some people thought he was born in Safed, a city in Palestine. Many followers of the Sabbatean movement claimed to be from Palestine.

As a young man, Ayllon was involved with Sabbatean groups in Thessaloniki. These groups had some unusual beliefs and practices.

A few years later, Ayllon traveled to Europe. He went as a meshullaḥ, which means a messenger. His job was to collect money for poor Jewish communities in Palestine. At this time, he seemed to have stopped openly supporting Sabbateanism.

Challenges in London

In 1688, Ayllon was in Livorno, Italy. From there, he went to Amsterdam and then to London. After a few months, he was chosen to be the haham in London on June 6, 1689.

However, his new position quickly faced problems. In 1690, a member of the community named Jacob Fidanque raised concerns about Ayllon's past. The community leaders, called the Ma'amad, tried to keep the issue quiet. But Ayllon's reputation was damaged. Many learned members of the community did not want to follow him.

This caused a lot of tension. The Ma'amad even issued a rule saying that only the appointed haham could make religious decisions. Anyone else doing so would be punished.

Moving to Amsterdam

Six years later, in 1696, Ayllon wrote that his relationship with the London community was still very difficult. His old Sabbatean beliefs also started to become known again. The community began thinking about asking him to resign.

Because of these problems, Ayllon decided to leave London. He was happy to accept a new role in 1701. He became an associate rabbi for the Sephardic community in Amsterdam.

A Big Disagreement

Ayllon faced new challenges in Amsterdam. In 1700, he was asked to review a book by Abraham Miguel Cardoso. Ayllon said the book was harmless. However, the Ma'amad did not fully trust his opinion. They asked other learned scholars to review it.

These scholars decided that Cardoso's book was heretical, meaning it contained beliefs against Jewish law. They even ordered the book to be publicly burned.

Around this time, Tzvi Ashkenazi became the rabbi of the Ashkenazic (German and Eastern European) community in Amsterdam. Ashkenazi was very learned and respected. He was also known for finding and speaking out against heretical ideas, especially those related to Sabbateanism. This made him a serious challenge for Ayllon.

The conflict became clear when a known Sabbatean, Nehemiah Ḥayyun, arrived. A scholar named M. Ḥagis asked Ashkenazi to examine Ḥayyun's writings. Ashkenazi declared them heretical in 1711. He also told the Ma'amad about his findings.

The Ma'amad, however, did not like a German rabbi telling them what to do. They said Ashkenazi's opinion needed to be supported by Ayllon and other members of their own group. Ashkenazi refused to work with Ayllon. He knew Ayllon was not an expert in Kabbalah (Jewish mysticism) and suspected Ayllon had ties to Sabbateanism.

Ayllon saw this as a chance to gain influence. He convinced an important member of the Ma'amad, Aaron de Pinto, that Ashkenazi was trying to interfere with their community's independence. It is not clear if Ayllon was secretly loyal to Sabbateanism or just wanted to protect Ḥayyun for personal reasons. Ḥayyun knew about Ayllon's past, so it might have been risky to make him an enemy.

De Pinto succeeded in getting the Ma'amad to pass a resolution. They refused to let the German rabbi interfere in their matters. They asked Ayllon to form a committee to give an official opinion on Ḥayyun's work.

On August 7, 1713, the committee's findings were announced in the Portuguese synagogue. They said Ḥayyun was innocent of heresy and had been unfairly treated. The committee had seven members, but their decision mostly reflected Ayllon's view. The other six members did not understand the complex issues.

The disagreement did not end there. Ashkenazi and Ḥagis had already banned Ḥayyun and his book on July 23. A long debate followed, involving rabbis from Germany, Austria, and Italy. Ayllon did not look good in these discussions. However, in Amsterdam, he seemed to win because Ashkenazi was forced to leave the city.

Ayllon allowed Ḥayyun to attack important Jewish leaders. He even gave Ḥayyun personal papers that criticized his opponent, Ḥagis. Ayllon also likely reported Ashkenazi to the Amsterdam authorities. This made the Jewish community's internal dispute a public matter.

It is said that when Ayllon heard about Ashkenazi's death in 1718, he admitted he had wronged him. A few years later, when Ḥayyun visited Amsterdam again, things had changed. Even Ayllon refused to see him. Solomon Ayllon died in Amsterdam in 1728.

Ayllon's Writings

Ayllon left behind a work about Kabbalah, which is a form of Jewish mysticism. A copy of this handwritten book is kept in the library of the Jews' College in London.

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |