Stephen Bocskai facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Stephen Bocskai |

|

|---|---|

| Prince of Transylvania and Hungary | |

|

|

| Prince of Transylvania | |

| Reign | 1605–1606 |

| Successor | Sigismund Rákóczi |

| Born | Bocskai István 1 January 1557 Kolozsvár, Eastern Hungarian Kingdom (now Cluj-Napoca, Romania) |

| Died | 29 December 1606 (aged 49) Kassa, Royal Hungary (now Košice, Slovakia) |

| Burial | 22 January 1607 St. Michael's Cathedral Gyulafehérvár, Transylvania (now Alba Iulia, Romania) |

| Spouse | Margit Hagymássy |

| Father | György Bocskai |

| Mother | Krisztina Sulyok |

| Religion | Reformed |

Stephen Bocskai (born January 1, 1557 – died December 29, 1606) was a very important leader. He was the Prince of Transylvania and Hungary from 1605 to 1606. He came from a noble family in Hungary. His family's lands were in the eastern part of the old Kingdom of Hungary. This area later became the Principality of Transylvania. Stephen spent his younger years at the court of Maximilian II. Maximilian was the ruler of Royal Hungary, which was the western and northern part of the old kingdom.

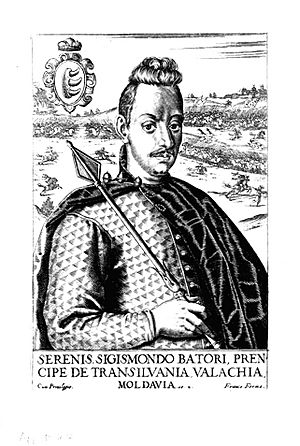

Bocskai's career began in 1581. His young nephew, Sigismund Báthory, became the ruler of Transylvania. In 1588, Bocskai supported Sigismund's idea to join a group against the Ottoman Empire. Sigismund made Bocskai the captain of Várad (now Oradea, Romania) in 1592. When Sigismund lost his throne in 1594, Bocskai helped him get it back. As a reward, Bocskai received lands from those who had opposed Sigismund.

In 1595, Bocskai signed a treaty for Transylvania to join the Holy League. He then led the Transylvanian army into Wallachia, which the Ottomans had taken over. The Christian armies freed Wallachia. They defeated the Ottoman army in the Battle of Giurgiu on September 29, 1595.

After some Ottoman victories, Sigismund gave up his throne in 1598. The new ruler, Rudolph, dismissed Bocskai. Bocskai then convinced Sigismund to return, but Sigismund gave up his throne again in 1599. The new prince, Andrew Báthory, took Bocskai's lands. Andrew Báthory was later removed by Michael the Brave of Wallachia. During this time of trouble, Bocskai had to stay in Prague. Rudolph's officials did not trust him. Bocskai started a rebellion against Rudolph in October 1605. This happened after his secret letters to the Ottoman Grand Vizier were found.

Bocskai hired Hajdús, who were irregular soldiers. He defeated Rudolph's military leaders. Bocskai gained control over more areas with the help of local nobles and citizens. They were also upset by Rudolph's harsh actions. Bocskai was chosen as prince of Transylvania on February 21, 1605. He became prince of Hungary on April 20. The Ottomans supported him. However, his own supporters worried that Ottoman help might threaten Hungary's freedom. To end the fighting, Bocskai and Rudolph's representatives signed the Treaty of Vienna on June 23, 1606. Rudolph recognized Bocskai's right to rule Transylvania and four counties in Royal Hungary. The treaty also gave Protestant nobles and citizens the right to practice their religion freely. In his last will, Bocskai said that Transylvania's independence was important for Hungary's special place within the Habsburg monarchy.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Stephen Bocskai was born on January 1, 1557, in Kolozsvár (now Cluj-Napoca, Romania). He was the sixth or seventh child of György Bocskai and Krisztina Sulyok. His father was a Hungarian nobleman. His family owned lands in Bihar and Zemplén Counties. Stephen's mother was related to important families. One of her sisters was married to István Dobó. Dobó was made a leader in Transylvania by Ferdinand I, the King of Hungary.

When Stephen was born, his father was in prison. He was held because Isabella Jagiellon, who had ruled eastern Hungary, had returned and imprisoned Ferdinand's supporters. A few months later, György Bocskai was released. He and his family settled in Kismarja. He changed his religion from Catholic to Calvinist in the 1560s. He died around 1570 or 1571.

Stephen Báthory, who became ruler in 1571, helped György Bocskai's orphaned children. Stephen Bocskai might have moved to Maximilian's court in Vienna as a teenager. He worked as a page there and started getting a salary in 1574. He returned to Vienna about a year later and became a steward.

After Stephen Báthory became King of Poland in 1575, he made his brother, Christopher Báthory, ruler of Transylvania. Christopher was married to Bocskai's sister, Elisabeth. Maximilian, who was tolerant of new religious ideas, died in 1576. His son, Rudolph, who was a strong Catholic, became ruler. Bocskai soon left Prague and moved to Transylvania. He did not get high positions under Christopher's rule. He was only a commander of a small group of soldiers in Várad.

Bocskai's Career

Early Political Roles

In 1581, the dying Christopher Báthory named Bocskai to the council that would rule Transylvania. This was during the time when Christopher's son, Sigismund Báthory, was too young to rule. Bocskai was the youngest member of this council. He had little power at first.

Bocskai married Margit Hagymássy, a wealthy widow, in late 1583. Her dowry included the fortress of Nagykereki and nearby villages. Stephen Báthory later ended the council and appointed János Ghyczy to rule for Sigismund in 1585. Bocskai remained a member of the royal council. After Stephen Báthory died in 1586, Bocskai went to Poland to discuss Báthory's will. He realized that Poland would no longer support Transylvania.

In 1588, Sigismund was declared old enough to rule. Bocskai stayed on the royal council. There were rumors about Sigismund's cousins trying to take his throne. Some rumors said Bocskai was Sigismund's most loyal advisor. Others accused him of plotting against the Báthory family. Around this time, Bocskai became close with the army commanders.

Captain of Várad

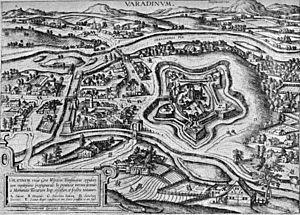

Sigismund Báthory decided to fight against the Ottoman Empire. His cousins strongly disagreed. Sigismund then replaced his cousin Stephen Báthory with Bocskai. He made Bocskai captain of Várad and head of Bihar County in May 1592. The captains of Várad commanded the strongest army in Transylvania. Bocskai, who was Calvinist, was told to protect Catholics in his new area. He continued to rebuild the fortress, which guarded an important route.

The Ottoman Sultan ordered his Grand Vizier to invade Royal Hungary in August 1593. Young Transylvanian nobles went to fight the Ottomans. However, most Transylvanian politicians wanted to avoid war. Sigismund still wanted to fight. Only Bocskai and Ferenc Geszthy supported him in the royal council.

In June 1594, Crimean Tatars attacked the Partium, forcing Bocskai to stay in Várad. Sigismund called a meeting, but the leaders of Transylvania refused to declare war. Balthasar Báthory then convinced Sigismund to give up his throne in July.

Bocskai and other army commanders convinced Sigismund to change his mind. Bocskai and his troops helped Sigismund return to power. On August 27, the leaders of Transylvania again swore loyalty to Sigismund. The next day, fifteen opposition leaders were arrested. Many of them were executed or killed. Years later, Sigismund said Bocskai forced him to order their deaths. Most historians agree that Bocskai was responsible. This made him Sigismund's most important advisor.

Bocskai became head of Inner Szolnok and Kraszna Counties. He received many lands taken from the executed nobles. This made him one of the richest landowners. For example, he gained fortresses at Marosvécs, Szentjobb, and Sólyomkő.

Fighting the Ottomans

Sigismund Báthory sent Bocskai to Prague in November 1594. Bocskai was to negotiate with the anti-Ottoman Holy League. He signed a treaty for Transylvania to join the League on January 28, 1595. Emperor Rudolph recognized Transylvania's independence. He also promised his niece, Maria Christina, to Sigismund. Bocskai married Maria Christina as Sigismund's representative on March 6. The Transylvanian leaders confirmed the treaty on April 16. Bocskai brought Maria Christina to Gyulafehérvár (now Alba Iulia, Romania) in July.

Sigismund Báthory ordered György Borbély to invade nearby Ottoman lands. Bocskai sent his deputy to help Borbély. The Transylvanian army forced the Ottomans to leave fortresses along the Maros River by October. Meanwhile, the Ottoman Grand Vizier had invaded Wallachia. The Wallachian ruler, Michael the Brave, had to retreat.

To help Michael of Wallachia, Sigismund Báthory promised the Székelys (a group of people) their freedom back if they joined his army. More than 20,000 Székelys joined. This allowed Sigismund to gather a large army. Although the prince led the army, Bocskai was the real commander. Their combined forces attacked Târgoviște on October 16. Two days later, Bocskai led the main attack. The Ottoman soldiers were forced to leave and were killed or captured. The Ottoman army then retreated to Giurgiu on the Danube River. On October 29, the remaining Ottoman soldiers were killed. The next day, the Ottoman fortress at Giurgiu was taken. After returning to Transylvania, Sigismund Báthory took back his promise to free the Székelys.

In January 1596, Sigismund Báthory went to Prague to discuss the war. Bocskai was left in charge of Transylvania. Bocskai soon faced problems with the Székely commoners. Their leaders threatened those who accepted serfdom. Bocskai sent troops to Székely Land to punish the leaders. His officers were very cruel in putting down the rebellion. This event was called the "Bloody Carnival" of 1596.

Sigismund Báthory returned in March 1596. He led his troops against Crimean Tatars and Ottomans. Bocskai again managed Transylvania. After many Ottoman victories, Sigismund began talks about giving up his throne to Rudolph. The agreement was signed in December 1597. However, Rudolph did not send his representatives for months. During this time, a Catholic leader accused Bocskai of plotting to take Transylvania. But Friar Carillo supported Bocskai. Bocskai convinced Sigismund to imprison the accuser. The prince also made Bocskai a baron in March 1598.

Times of Trouble

On April 8, 1598, the Transylvanian leaders swore loyalty to Rudolph. Rudolph appointed three officials to rule Transylvania. They did not trust Bocskai and removed him from his positions. Bocskai knew his nephew Sigismund Báthory regretted giving up his throne. Bocskai gathered his troops to help Sigismund return. After Sigismund came back, Bocskai called a meeting. He convinced the leaders to swear loyalty to Sigismund again on August 21. The officials Rudolph sent were expelled.

Bocskai was again made the supreme commander of the Transylvanian army. However, his former deputy did not obey him. He allowed Rudolph's troops to take Várad. An Ottoman army then attacked the Partium in October. They also took Bocskai's lands. Sigismund offered Transylvania to his cousin, Andrew Báthory. Sigismund kept this secret from Bocskai. Bocskai had always been against Andrew's pro-Ottoman ideas. To get rid of his uncle, Sigismund sent Bocskai to Prague to talk with Rudolph in late 1598.

Bocskai was still in Prague when Sigismund gave up his throne to Andrew in March 1599. Bocskai returned to Transylvania as Rudolph's envoy. He refused to swear loyalty to Andrew. He settled in his fortress at Szentjobb in August. Andrew accused Bocskai of murder. When Bocskai ignored him, his lands were taken in October. However, this only happened in Transylvania proper. The Partium was controlled by the emperor's supporters. Bocskai planned to invade Transylvania. But Michael of Wallachia acted first. Michael defeated Andrew in the Battle of Sellenberk on October 28. Michael entered Gyulafehérvár, and peasants killed Andrew.

After Michael's victory, Bocskai hired Hajdús and went to Kolozsvár. He thought Michael would leave Transylvania. He urged Giorgio Basta, Rudolph's army commander, to send new officials to end the chaos. Michael took control of Transylvania. The leaders recognized him as Rudolph's representative. Transylvania fell into chaos with plundering by different armies. Bocskai returned to the Partium. But Rudolph ordered him to join Michael in Gyulafehérvár in November. Michael tried to use Bocskai to get fortresses to swear loyalty to him. But Bocskai did not want to be Michael's subordinate. He realized Michael would not give him back his lands. So, he left Transylvania and settled in Szentjobb in early 1600.

Bocskai wrote to Rudolph, calling Michael a trickster. But Rudolph's new officials did not trust Bocskai. They even called him "the Pestilence." Transylvanian nobles blamed Bocskai for the anti-Ottoman policy that had ruined the principality. They convinced Basta to expel Michael from Transylvania in September. Sigismund Báthory tried to get Bocskai's support again. Bocskai handed Sigismund's envoy over to Rudolph's official. But this did not earn him trust. Basta even planned to kill Bocskai. On November 25, the Transylvanian leaders took Bocskai's lands and banished him.

Bocskai went to Prague in January 1601 to clear his name. Michael of Wallachia also came to Prague. He convinced Rudolph to let him return to Transylvania. Bocskai was not allowed to leave Prague. Michael and Basta defeated Sigismund Báthory on August 3. But Basta had Michael killed thirteen days later. Basta's soldiers often plundered Transylvanian towns. Bocskai returned to the Partium by the end of 1601. But he was called back to Prague in April 1602. He became the emperor's advisor. He could only leave Prague in late 1602. He settled in Szentjobb again. He tried to get his confiscated lands back, but Basta strongly opposed him.

From 1603, Rudolph's officials took lands from wealthy nobles. They did this through legal processes. In early 1604, the captain of Kassa took the St. Elisabeth Cathedral from Protestants and gave it to Catholics. Rudolph then stopped the Hungarian Diet from discussing religious issues. The captain also tried to borrow money from Bocskai. When Bocskai refused, the captain collected taxes on Bocskai's lands that were supposed to be tax-free. He also imprisoned Bocskai's nephew until Bocskai paid a ransom.

Gabriel Bethlen, a leader of Transylvanian nobles who had fled to the Ottoman Empire, urged Bocskai to rebel against Rudolph. But Bocskai refused. To reward Bocskai's loyalty, Rudolph gave him back almost all his lands in Transylvania on July 2, 1604. Bocskai visited Transylvania. He saw that towns and villages were almost completely destroyed. He became convinced that only an independent Transylvania, supported by the Ottomans, could restore Hungary's freedom. On September 20, he learned that his letters to the Ottoman Grand Vizier had been found. Fearing punishment, Bocskai pretended to be sick. In reality, he ordered his castle guards to prepare for resistance. But one of them told Rudolph's deputy about Bocskai's plans.

Uprising and Rule

Early Victories

Rudolph's deputy captured Bocskai's fortress at Szentjobb on October 2. However, the guard of Bocskai's other castle, Nagykereki, hired 300 Hajdús. This allowed him to defend the fortress. Rudolph's commander sent an army against Bocskai. But Bocskai's agents convinced the Hajdús to leave the commander's army. This allowed Bocskai to defeat Rudolph's forces near Álmosd on October 15. The commander retreated towards Kassa. But the mostly Protestant townspeople did not let him in. The mayor convinced the citizens to let Bocskai's Hajdús enter the town on October 30.

Bocskai issued a statement from Kassa to the nobles. He reminded them of Rudolph's harsh actions. Leaders from the counties and towns of Upper Hungary came to Kassa. They voted to provide money to continue the fight. Bocskai made young Protestant lords the commanders of his army. He made a Catholic nobleman his chancellor. Rudolph sent a large army against the rebels. This army defeated some Hajdús on November 17.

Gabriel Bethlen came to Kassa on November 20. He brought a message from the Ottoman Sultan to Bocskai. The message called Bocskai prince of Transylvania. The Ottomans also sent more soldiers to Bocskai. Rudolph's army defeated Bocskai near Edelény on November 27. But they could not capture Kassa. They retreated in early December. Bocskai sent letters to Transylvania, asking for support. A Székely nobleman was the first to join him. He helped convince the Székelys to forgive Bocskai for the "Bloody Carnival." Bocskai had a Hajdú captain executed for questioning his leadership. He made an alliance with the ruler of Moldavia. He also promised the Székelys their freedom. This helped him secure his rule in Transylvania.

Becoming Prince

The leaders of the Transylvanian nobles and the Székelys elected Bocskai prince on February 21. However, the Transylvanian Saxons and the citizens of Kolozsvár remained loyal to Rudolph. Bocskai sent messages to European royal courts in March. He accused Rudolph of being a tyrant. He listed Rudolph's unlawful actions that caused the rebellion. Rudolph offered him forgiveness, but Bocskai refused on March 24.

Rudolph's army retreated in early April. Leaders from 22 counties in Upper Hungary and Partium met. They all declared Bocskai prince of Hungary on April 20. Although other counties did not recognize his rule, Bocskai wanted to unite Hungary. He asked the Ottoman Sultan to send him a royal crown.

Bocskai's army captured many towns in May. They also plundered parts of Austria, Moravia, and Silesia. The Saxons of Brassó (now Brașov, Romania) recognized Bocskai's rule. The citizens of Kolozsvár also swore loyalty to him on May 19. Bocskai went to Transylvania in August. His army captured Segesvár (now Sighișoara, Romania) on September 9. This ended the Saxons' resistance. The leaders of Transylvania paid respect to him on September 14.

Peace Treaties

The Ottomans took advantage of Bocskai's rebellion. The Grand Vizier captured Esztergom on October 3. Bocskai's commander prevented his Ottoman allies from entering another town. Bocskai met the Grand Vizier in Pest on November 11. The Grand Vizier called Bocskai king and gave him a royal crown. But Bocskai refused to accept it as a king's symbol.

After Esztergom fell to the Ottomans, important nobles realized only the Habsburgs could stop the Ottomans. They convinced Bocskai to start talks with Rudolph's brother, Matthias. Matthias wanted to remove Rudolph from power. Although some groups still opposed peace, the Diet allowed Bocskai to send his envoys to Vienna. On December 12, Bocskai gave special noble status to 9,254 Hajdús. He settled them on his lands.

Bocskai's envoy reached an agreement in Vienna on February 9, 1606. The royal court agreed to restore Hungary's traditional government. They also confirmed most freedoms for nobles and citizens. But they did not want to recognize Transylvania's independence under Bocskai. On April 4, the Transylvanian Diet allowed Bocskai to sign a treaty with the Habsburgs.

The talks ended with the Treaty of Vienna, signed on June 23. This new treaty confirmed the right of Protestant nobles and citizens to practice their religion freely. Bocskai was recognized as the hereditary prince of Transylvania. Transylvania was expanded to include four more counties and the castle of Tokaj. Bocskai confirmed the treaty on August 17.

Bocskai wanted to help make peace between the Habsburgs and the Ottoman Empire. On November 24, Rudolph said that Transylvania could remain independent even if Bocskai died without sons. The Peace of Zsitvatorok, which ended the Long Turkish War, was signed on November 11.

Final Months

Bocskai had health problems in 1606. On December 13, he called a meeting in Kassa. Four days later, he wrote his last will. He urged his successors to keep Transylvania independent as long as the Habsburgs ruled Royal Hungary. He named Bálint Drugeth as his successor. Stephen Bocskai died in Kassa on December 29.

Bocskai's sudden death led to rumors. The Hajdús accused his chancellor of poisoning him. They also claimed the chancellor changed Bocskai's will. This was supposedly to stop Gábor Báthory from taking the throne. The Hajdús attacked the chancellor in Kassa and killed him on January 12, 1607.

Bocskai's body was taken to Gyulafehérvár for burial on February 3. Drugeth led the procession. But the Transylvanian leaders did not want to elect him ruler. Instead, they chose Sigismund Rákóczi as prince on February 11. Bocskai was buried in the St Michael's Cathedral in Gyulafehérvár on February 22.

As long as the Hungarian Crown is with a nation mightier than us, with the German, and the Hungarian Kingdom is also dependent of the Germans, it will be necessary and expedient to have a Hungarian prince in Transylvania, for he shall provide protection and be of use to them. If, may God grant, the Hungarian Crown were at Hungarian hands in a Hungary under a crowned king, we urge the Transylvanians neither to secede from it, nor to resist to it, but rather to make efforts, according to their abilities and with united will, to subject themselves to that Crown in the ancient way.

—Excerpt from Bocskai's last will

Legacy

Even before his death, Bocskai's supporters saw his rebellion as a fight for Hungary's freedom. Many historians today also see him as a leader of a national movement. This movement was a step towards later Hungarian fights for independence. Others say Bocskai, who was allied with the Ottomans, did not fight for a fully independent Hungary. They believe he could only hope to rule a country under Ottoman control. For example, Géza Pálffy points out that most Hungarian nobles stayed loyal to the Habsburg ruler. So, Bocskai's rebellion could be seen as a civil war.

Bocskai was also seen as a defender of religious freedom. The Hajdús who joined him said they wanted to "defend Christianity, our country and dear homeland, and especially the one true faith" (meaning Calvinism). After Bocskai's death, his priest described him as a new Moses. Bocskai was the first Calvinist prince of Transylvania. His statue is on the Reformation Wall in Geneva, Switzerland.

Although the Peace of Vienna and the laws of 1608 were eroded and partially neutralised as time went on by the pressures of Habsburg absolutism, they nevertheless represented an important landmark in Hungary's development and a valuable set of precedents for a people adept in the use of precedents. The new laws maintained and strengthened Hungary's claim to special treatment among the lands ruled by the Habsburg Monarchy; they established, for Hungary, the principle of religious freedom and ensured that Hungary would once again – for the time being, at least – be governed by Hungarian officers of state through the Hungarian Diet, and a Hungarian treasury. István Bocskai's achievement, of which he did not live to see the fruits, was substantial.

—Bryan Cartledge: The Will to Survive: A History of Hungary

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Esteban Bocskai para niños

In Spanish: Esteban Bocskai para niños