Joris Hoefnagel facts for kids

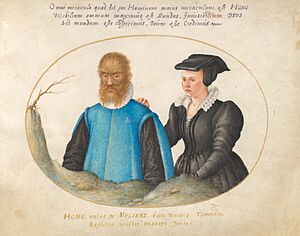

Joris Hoefnagel (born in Antwerp in 1542 – died in Vienna on July 24, 1601) was a talented artist from Flanders. He was a painter, printmaker, and a special kind of artist called a miniaturist. He was known for drawing nature, landscapes, and even mythological scenes.

Hoefnagel was one of the last artists to create beautiful illuminated manuscripts (books decorated by hand). He also helped develop landscape drawing. His detailed drawings of plants and animals were very important. They helped start a new type of art called still-life painting, especially flower paintings, in Europe. His work also helped scientists study nature more closely.

Contents

Life of Joris Hoefnagel

Early Years and Learning

Joris Hoefnagel's father sold diamonds and fancy items like tapestries. His family wanted him to join the business, so he received a good education. He learned several languages, wrote poetry, and played music.

Hoefnagel said he taught himself art. However, some say he learned from another artist named Hans Bol in Antwerp. Hans Bol might have taught him how to create tiny, detailed miniature paintings.

Travels and Adventures

From 1560 to 1562, Hoefnagel lived in France, where he studied at universities. He probably made his first landscape drawings there. He had to leave France in 1563 because of religious problems and went back to Antwerp.

Soon after, he traveled to Spain (1563-1567) for his family's business. He drew many places in Spain, especially Seville. This city was a big trading port, and he saw many interesting animals and plants there.

He returned to Antwerp in 1567. In 1568, he visited London, England, and made friends with other Flemish business people. In 1571, Joris Hoefnagel married Suzanne van Onchem. Their son, Jacob, born in 1573, also became an artist.

Life in Exile

In 1576, Spanish soldiers attacked Antwerp, and Hoefnagel's family lost much of their money. So, Joris Hoefnagel left his hometown. In 1577, he traveled with his friend, the mapmaker Abraham Ortelius, through Germany and Italy. They visited cities like Frankfurt, Augsburg, Munich, Venice, and Rome.

In Augsburg, he met people who recommended him to the Duke of Bavaria, Albert V. The Duke liked Hoefnagel's miniature paintings and offered him a job as a court painter. Hoefnagel decided to work for the Duke in Munich, where he stayed for about eight years. He also worked for other important families.

Because he was a Calvinist (a type of Christian), Hoefnagel had to leave Munich in 1591. This was because everyone at the court had to be Catholic. He then began working for Emperor Rudolf II. He lived in Frankfurt, where he met other artists and scholars. His friendship with the botanist Carolus Clusius was important for his later plant drawings.

In 1594, he had to leave Frankfurt because his faith was no longer allowed there. He spent his last years in Vienna but often visited Prague. His brother Daniel lived in Vienna. Joris Hoefnagel helped his son Jacob get work at the court. He often worked with Jacob on art projects.

Hoefnagel's Artworks

Hoefnagel was an artist who could do many different things. He created landscapes, miniature paintings, and drawings of nature. He also made topographical drawings (detailed maps or views of places).

Landscapes and City Views

When he visited England, Hoefnagel drew royal palaces like Windsor Castle. These are some of the earliest realistic landscape drawings in England.

Hoefnagel made many landscape drawings during his travels. These drawings were later used for engravings in famous books. One was Ortelius' Theatrum orbis terrarum (1570), a world atlas. Another was Braun's Civitates orbis terrarum (1572–1618), a huge atlas of cities. Hoefnagel worked on the Civitates throughout his life. He created over 60 illustrations himself, including views of cities in Bavaria, Italy, and Bohemia. His detailed and accurate drawings helped shape landscape art in the 17th century.

His son Jacob later used his father's designs for the sixth volume of the Civitates, published in 1618. This volume showed cities in Central Europe. The views were very accurate, showing the land, roads, and buildings in great detail.

Emblem Drawings

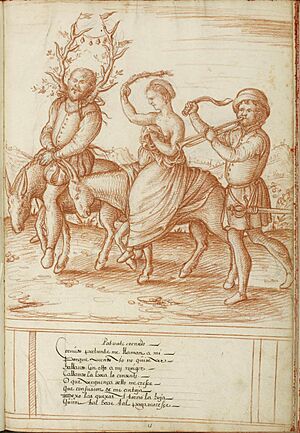

In England, Hoefnagel created a series of drawings called Patientia (meaning "Patience"). These drawings focused on themes of patience and suffering. This work was like an early version of later "emblem books" from the Netherlands. Emblem books used pictures with short texts to teach moral lessons. Hoefnagel's Patientia manuscript is now in a library in France.

Illuminated Manuscripts

Hoefnagel was a very skilled miniature painter. He is famous for his tiny, detailed work on several manuscripts for the Habsburg royal family.

The Book of Hours of Philippe of Cleves In the late 1570s or early 1580s, Hoefnagel added beautiful decorations to the edges of this old prayer book. He used themes like split oranges and bright Maltese crosses, which appeared in his later works too.

Roman Missal Between 1581 and 1590, he illustrated a Roman missal (a book used for church services) for Archduke Ferdinand II. He added decorations throughout the book, including nature scenes and fancy borders. The calendar pages had small pictures of games, instruments, and animals. These images often had a deeper meaning related to the religious text.

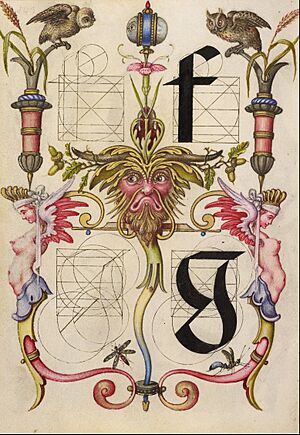

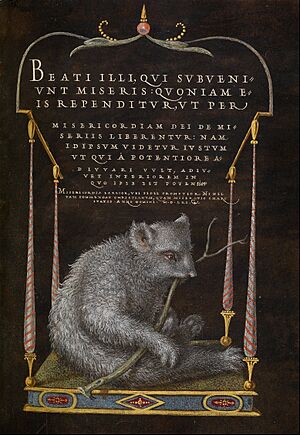

Schriftmusterbuch Emperor Rudolf II asked Hoefnagel to add miniatures to a manuscript called Schriftmusterbuch (meaning "Pattern Book of Writing") between 1591 and 1594. This book was originally made by a calligrapher (someone who writes beautifully) named Georg Bocskay. Hoefnagel added tiny paintings using watercolors and gold. He also added eight pages that were entirely his own work. He used pictures of plants, animals, myths, portraits, city views, and battle scenes to honor the Emperor.

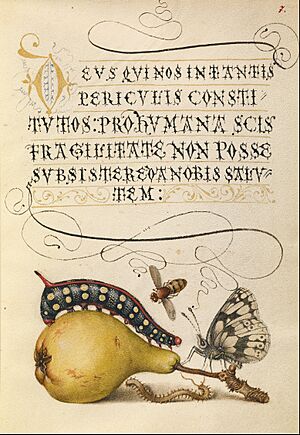

Mira calligraphiae monumenta

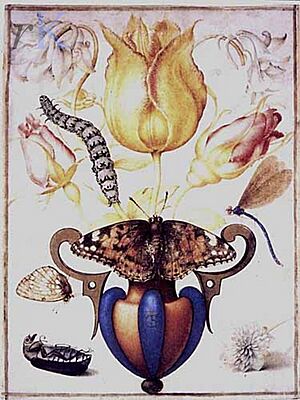

Emperor Rudolf II also asked Hoefnagel to illustrate the Mira calligraphiae monumenta (the Model Book of Calligraphy). He started this work around 1590. This book was also originally made by Georg Bocskay to show different styles of writing. When the Emperor owned it, Hoefnagel added illustrations of plants, fruits, flowers, small animals, insects, and city views. His pictures showed a wide range of the natural world. He even decorated tiny letters with strange creatures and masks.

Hoefnagel's goal was to show how powerful images could be, even more than written words. This book is one of the last important examples of European illuminated manuscripts. It was made at a time when printed books were becoming much more common.

Hoefnagel's miniature paintings are similar to the Flemish miniature art from the 15th and 16th centuries. He was very careful with details and used tricks like shadows to make things look three-dimensional. He loved to show off his skill by painting difficult subjects, like an apple cut in half or an insect with shiny skin.

Nature Studies

Hoefnagel's motto was 'natura magistra' (nature his teacher). This shows his strong interest in drawing nature realistically. He started drawing miniature animals before he left Antwerp. These early drawings helped him get his job with the Dukes in Munich.

He organized his nature drawings into a four-volume manuscript called The Four Elements. This huge book has about 300 miniature paintings and thousands of notes. It shows thousands of animals, grouped by the four elements: fire, earth, water, and air. This book was an important scientific work in the 16th century, showing almost all the animals known at the time.

Archetypa studiaque patris Georgii Hoefnagelii In 1592, his son Jacob published a book called Archetypa studiaque patris Georgii Hoefnagelii in Frankfurt. This book has 48 engravings (prints) of plants, insects, and small animals, all drawn from real life by Joris Hoefnagel. Some people believe these engravings were the first to use a microscope, but this is still debated.

The prints in this collection were not just pictures of the real world. They also had a religious meaning, encouraging people to think about God's creation. Each print had a motto, often about God's influence. Other artists used these prints as models, and Hoefnagel's designs were copied for centuries.

Still Life Paintings

Hoefnagel played a big part in developing still-life painting, especially flower still lifes. An undated flower painting by Hoefnagel, done as a miniature, is the first known independent still life. He made his flower paintings lively by adding insects and paying close attention to detail, just like in his nature studies.

Hoefnagel's illuminated manuscripts, the prints from Archetypa studiaque, and some of his drawings on vellum (a type of parchment) helped start still-life painting as its own art form. This was especially important for the Dutch style of still lifes with flowers, shells, and insects. After Hoefnagel died, some of his art went to the Huygens family in the Netherlands. A Dutch artist named Jacob de Gheyn II saw these works and became one of the first flower still-life painters.

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |