Stramenopile facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Stramenopile |

|

|---|---|

|

|

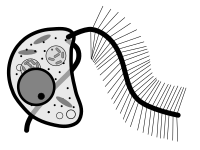

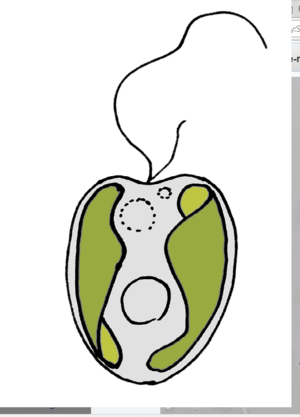

| Ochromonas sp. (Chrysophyceae), with two unequal (heterokont) flagella. Mastigonemes not represented. | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Clade: | SAR |

| Clade: | Stramenopiles Patterson 1989 |

| Phyla and subphyla | |

|

|

| Synonyms | |

|

|

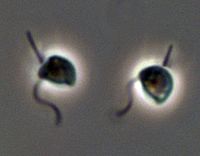

The Stramenopiles, also known as Heterokonts, are a special group of living things. What makes them unique is that most of them have tiny, stiff hairs on their bodies or on their whip-like tails called flagella. These hairs help them move around or catch food.

Stramenopiles are eukaryotes, which means their cells have a nucleus. They are not animals, plants, or fungi. Instead, they belong to a diverse group called protists. Most stramenopiles are single-celled, meaning they are made of just one cell. However, some are multicellular, like the large brown algae (seaweeds) you might see at the beach.

Many stramenopiles have two flagella. One flagellum usually has rows of these stiff hairs, while the other is smooth and often shorter. These tiny hairs are a key feature that helps scientists identify Stramenopiles.

Contents

Discovering Stramenopiles

The name 'Stramenopile' was first used by a scientist named D. J. Patterson in 1989. He wanted a clear way to describe this group of organisms. Before this, they were often called 'Heterokonts'.

What's in a Name?

The word 'heterokont' means "different flagella." It was used to describe organisms with two flagella of different types. However, this term became confusing because different scientists used it to mean slightly different groups of organisms over time.

For example, in 1899, 'Heterokontae' was used for a type of algae. Later, in 1956, it included other groups like chrysophytes and oomycetes. This made it hard to know exactly which organisms were being talked about.

To make things clearer, scientists introduced 'Stramenopile'. This name helps identify a specific group of organisms that share a unique feature: the stiff, three-part hairs. These hairs are usually found on their flagella. Even if some Stramenopiles have lost these hairs over time, their genes still show they are related.

Special Features

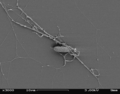

The stiff hairs on Stramenopiles' flagella are very unique. Each hair has three parts:

- A flexible base that connects to the cell.

- A long, stiff tube, like a tiny straw.

- Many delicate hairs at the very tip.

These special hairs are made from proteins found only in Stramenopiles. Even some Stramenopiles that don't have these hairs anymore, like most diatoms, still have the genes for these proteins.

Most Stramenopiles have two flagella near the top of their bodies. These flagella are supported by tiny tubes called microtubules, arranged in a special pattern.

How They Get Food

Many Stramenopiles have special parts called plastids. These plastids allow them to perform photosynthesis. This means they can use sunlight to make their own food, just like plants! Their plastids can be off-green, orange, golden, or brown. This is because they contain different pigments like chlorophyll a, chlorophyll c, and fucoxanthin.

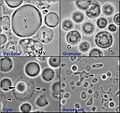

The most well-known Stramenopiles that make their own food are the brown algae (like kelp) and diatoms. Diatoms are super important because they produce a lot of food in oceans and fresh water.

Scientists believe that the first Stramenopiles did not have plastids and got their food by eating other organisms. Later, some of them gained the ability to photosynthesize. Some Stramenopiles have even gone back to eating other organisms after having plastids for a while.

Where They Live and What They Do

Stramenopiles live in many different places and play many roles in nature. Some are very important for the environment, while others can be parasites.

- Food Producers: Diatoms are tiny, single-celled Stramenopiles that are major food producers in oceans and lakes. They are a huge part of the food web and help cycle carbon around the planet.

- Seaweeds: Brown algae, like kelp and wrack, are large Stramenopiles that form underwater forests. They provide food and shelter for many marine animals.

- Bacteria Eaters: Some Stramenopiles, like Cafeteria, are tiny organisms that eat bacteria. They help recycle nutrients in water environments.

- Parasites: Not all Stramenopiles are helpful. Blastocystis can be a parasite in human intestines. Oomycetes, sometimes called water molds, include plant diseases like Phytophthora infestans, which caused the famous potato blight.

Family Tree

Stramenopiles and Their Relatives

Stramenopiles are part of a larger group called the SAR supergroup. This group also includes Alveolata and Rhizaria. The "SAR" comes from the first letters of these three groups. All members of the SAR supergroup have a special type of mitochondria (the powerhouses of the cell).

Scientists believe that the ancestor of the SAR supergroup once "captured" a tiny red alga and used it to make food. Many Stramenopiles still have plastids that show signs of this event. These plastids are surrounded by four membranes, which is a clue to their history.

| SAR |

|

||||||||||||

Groups Within Stramenopiles

The Stramenopiles group is very diverse, with many different types of organisms. Here are some of the main subgroups:

- Ochrophyta: This large group includes most of the Stramenopiles that can photosynthesize. It contains:

* Brown algae (Phaeophyceae): Large seaweeds like kelp. * Diatoms (Bacillariophyceae): Tiny, single-celled algae with glass-like shells. * Golden algae (Chrysophyceae): Often found in fresh water. * Yellow-green algae (Xanthophyceae): Another group of algae.

- Pseudofungi: This group includes organisms that look like fungi but are not. The most well-known are:

* Oomycetes: These are often plant pathogens, like the one causing potato blight.

- Bigyra: This group includes many Stramenopiles that do not photosynthesize and instead eat other organisms. Some examples are:

* Bicosoecida: Tiny organisms that eat bacteria. * Labyrinthulomycetes: Slime molds found in marine environments. * Opalinata: Parasites that live in the guts of cold-blooded animals.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Heterokonta para niños

In Spanish: Heterokonta para niños

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |