Subh-i-Azal facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Subh-i-Azal

|

|

|---|---|

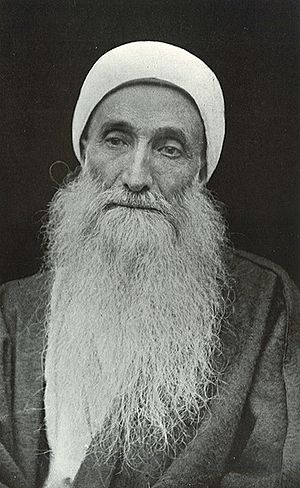

Ṣubḥ-i Azal at the age of 80, Famagusta, circa 1911

|

|

| Born |

Mírzá Yahya Núrí

1831 Tehran, Iran

|

| Died | April 29, 1912 (aged 80–81) (In the lunar calendar he would have been about 82-3.) Famagusta, present-day Cyprus

|

| Known for | Leader of Azali Babism |

| Title | Subh-i-Azal |

| Successor | Disputed |

Ṣubḥ-i-Azal (1831–1912), born Mírzá Yaḥyá, was an important religious leader from Iran. He led a group called Azali Bábism. He is mostly known for his disagreements with his half-brother, Baháʼu'lláh, about who should lead the Bábí community after 1853.

In 1850, when he was just 19 years old, the Báb chose him to lead the Bábí community. When Bábís faced attacks in 1852, Subh-i-Azal went to Baghdad. He stayed there for 10 years. Later, he joined other Bábí exiles who were called to Istanbul.

During his time in Baghdad, problems grew between him and Baháʼu'lláh. Many Bábí visitors started looking to Baháʼu'lláh for leadership. The government then sent the group to Edirne. There, Baháʼu'lláh announced he had a special message from God. This made the tension between the brothers much worse. It even led to a public debate that Subh-i-Azal did not attend.

In 1868, the government sent Subh-i-Azal and his followers to Famagusta, Cyprus. Baháʼu'lláh and his followers were sent to Akko. When Cyprus came under British control in 1878, Subh-i-Azal lived a quiet life. He received a pension from the British and met with many Sufi religious people on the island.

After Subh-i-Azal died in 1912, the Azali form of Babism became less active. It has not grown much since then. Most Bábís either followed Baháʼu'lláh or slowly returned to Islam. By 1904, only a small number of Azal's followers remained. Baháʼu'lláh was widely seen as the Báb's spiritual successor. In 2001, it was thought there were only a few thousand Azalis, mostly in Iran. A 2009 report mentioned a very small number in Uzbekistan.

Template:TOC limit=3

Contents

Understanding His Name and Title

Subh-i-Azal's most famous title means "Morning of Eternity." This name comes from an old Islamic story. The Báb, who started the Bábí faith, mentioned this story in one of his books.

It was common for Bábís to receive special titles. The Báb's will, a very important document, directly addressed Mirza Yahya. It called him "Name of Azal." This showed his special place.

Some experts say that Mirza Yahya was the only Bábí to have a title like "Azal." The Báb gave him titles like "Morning of the Eternal" or "Highness of the Eternal." He was also known by other names such as al-Waḥīd and at-Tamara.

His Life Story

Early Years

Subh-i-Azal was born in 1831 in Mazandaran, Iran. His father was a minister in the court of Fath-Ali Shah Qajar, the king. His mother died when he was born. His father died when he was three years old. This meant he became an orphan very young. His stepmother, who was Baháʼu'lláh's mother, took care of him.

Becoming a Bábí Follower

Around 1845, when he was about 14, Subh-i-Azal became a follower of the Báb. The Báb was the founder of the Bábí faith.

Early Activities in the Bábí Community

Subh-i-Azal met Táhirih, an important early Bábí leader. She traveled to Nur to spread the Bábí faith. She later met Subh-i-Azal and asked him to join her. He stayed in Nur for three days, sharing the new faith.

During a conflict called the Battle of Fort Tabarsi, Subh-i-Azal, Baháʼu'lláh, and another Bábí tried to help the Bábí soldiers. However, they were arrested before they could reach the fort. Subh-i-Azal managed to escape for a short time but was caught again. He was treated badly on his way to Amul. When he arrived, he was reunited with the other prisoners. They were ordered to be beaten. Baháʼu'lláh stepped in and offered to take Subh-i-Azal's beating instead. Later, the prisoners were released and sent home.

Becoming the Báb's Successor

Before the Báb was executed, he wrote some important letters. These letters were given to Subh-i-Azal and Baháʼu'lláh. Both Azalis and Baháʼís later saw these letters as proof that the Báb chose Subh-i-Azal to lead. Some sources say the Báb did this because Baháʼu'lláh suggested it.

After the Báb's death, Subh-i-Azal was seen as the main leader of the Bábí movement. Most Bábís looked to him for guidance.

While both Baháʼu'lláh and Subh-i-Azal were in Baghdad, Baháʼu'lláh publicly said that Subh-i-Azal was the community's leader. But Subh-i-Azal often stayed hidden. So, Baháʼu'lláh handled many of the daily tasks for the Bábí community.

Then, in 1863, Baháʼu'lláh announced to a few followers that he was "Him Whom God Shall Make Manifest." This was a special figure mentioned in the Báb's writings. In 1866, he made this claim public. Baháʼu'lláh's claim challenged Subh-i-Azal's leadership. If a new religion was starting, being the leader of the old one would mean less. Subh-i-Azal strongly disagreed with Baháʼu'lláh's claims. But his efforts to keep the old Bábí faith were not popular. His followers became a smaller group.

Subh-i-Azal's leadership was not always easy. He often stayed hidden in Baghdad. He communicated with Bábís through special agents. He did this because he wanted to stay safe, as the Báb had told him to protect himself.

Challenges to Baháʼu'lláh's Authority

In 1863, Baháʼu'lláh claimed to be the special figure mentioned in the Báb's writings. He made this public in 1866. This claim challenged Subh-i-Azal's role as leader. Subh-i-Azal responded by making his own claims. He tried to keep the traditional Bábí faith. However, his efforts were not popular, and his followers became a smaller group.

Exile and Later Life

In 1863, the Ottoman government sent most Bábís to Adrianople. In Adrianople, Baháʼu'lláh made his claim to be the special figure from the Bayan public. This caused a lasting split between the two brothers. Subh-i-Azal disagreed with Baháʼu'lláh's claims and new ideas. He tried to keep the original Bábí teachings, but most people did not follow him. During this time, there were many arguments between the two groups.

The fighting between the groups eventually led the Ottoman government to send them away again in 1868. Baháʼu'lláh and his followers, the Baháʼís, were sent to Akko. Subh-i-Azal, his family, and some followers were sent to Famagusta in Cyprus.

Family Life

Subh-i-Azal had several wives and many children. He had at least nine sons and five daughters. Some of his sons were named Nurullah, Hadi, Ahmad, Abdul Ali, and Rizwan Ali. Some reports say he had up to seventeen wives over his lifetime.

Who Came Next?

There are different stories about who Subh-i-Azal chose to lead after him. Some say he chose the son of Aqa Mirza Muhammad Hadi Daulatabadi. Others say he said that whichever of his sons "resembled him the most" would be the next leader. However, none of his sons seemed to step forward to lead.

One expert, Denis MacEoin, says that Subh-i-Azal appointed his son, Yahya Dawlatabadi, as his successor. But there is little proof that Yahya Dawlatabadi was involved in the religion. He spent his time working as a reformer in other areas.

After the deaths of the Azali Bábís who were active in the Iranian Constitutional Revolution, the Azali form of Babism became less active. It has not recovered because there is no clear leader or main organization. Today, it is thought that there are only a few thousand Azalis left.

His Writings

Many of Subh-i-Azal's writings are kept in important libraries around the world. These include the British Museum Library in London, Cambridge University, the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris, and Princeton University. Some of his works can also be found online.

An expert named E.G. Browne listed many of Subh-i-Azal's works. Here are some of the titles:

- Kitab-i Divan al-Azal bar Nahj-i Ruh-i Ayat

- Kitab-i Nur

- Kitab-i ʻAliyyin

- Kitab-i Lamʻat al-Azal

- Kitab-i Hayat

- Kitab-i Jamʻ

- Kitab-i Quds-i Azal

- Kitab-i Avval va Thani

- Kitab-i Mirʼat al-Bayan

- Kitab-i Ihtizaz al-Quds

- Kitab-i Tadliʻ al-Uns

- Kitab-i Naghmat ar-Ruh

- Kitab-i Bahhaj

- Kitab-i Hayakil

- Kitab fi Tadrib ʻadd huwa bi'smi ʻAli

- Kitab-i Mustayqiz

- Kitab-i Laʼali va Mujali

- Kitab-i Athar-i Azaliyyih

- Sahifih-ʼi Qadariyyah

- Sahifih-ʼi Abhajiyyih

- Sahifih-ʼi Ha'iyyih

- Sahifih-ʼi Vaviyyih

- Sahifih-ʼi Azaliyyih

- Sahifih-ʼi Huʼiyyih

- Sahifih-ʼi Anzaʻiyyih

- Sahifih-ʼi Huviyyih

- Sahifih-ʼi Marathi

- Alvah-i Nazilih la tuʻadd va la tuhsa

- Suʼalat va Javabat-i bi Hisab

- Tafsir-i-Surih-i-Rum

- Kitab-i Ziyarat

- Sharh-i Qasidih

- Kitab al-Akbar fi Tafsir adh-Dhikr

- Baqiyyih-ʼi Ahkam-i Bayan

- Divan-i Ashʻar-i ʻArabi va Farsi

- Divan-i Ashʻar-i ʻArabi

- Kitab-i Tuba (Farsi)

- Kitab-i Bismi'llah

Images for kids