Baháʼu'lláh facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Baháʼu'lláh

|

|

|---|---|

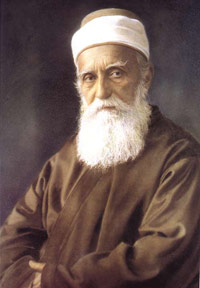

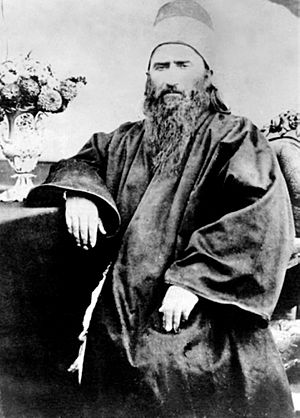

Photo of Baháʼu'lláh taken in Adrianople in 1868

|

|

| Born |

Mírzá Ḥusayn-ʻAlí Núrí

12 November 1817 |

| Died | May 29, 1892 (aged 74) |

| Resting place | Shrine of Baháʼu'lláh |

| Nationality | Persian |

| Known for | Founder of the Baháʼí Faith |

| Successor | ʻAbdu'l-Bahá |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children |

|

Baháʼu'lláh (born Ḥusayn-ʻAlí; November 12, 1817 – May 29, 1892) was the founder of the Baháʼí Faith. He came from a wealthy family in Persia (now Iran). He was sent away from his home because he followed the Bábí Faith, a new religion.

In 1863, in Iraq, Baháʼu'lláh announced that he had received a message from God. He spent the rest of his life as a prisoner in the Ottoman Empire. His teachings focused on important ideas like unity and spiritual growth for everyone. He also taught about how the world should be governed.

Baháʼu'lláh did not go to school, but he read a lot and was very religious. His family was rich, but when he was 22, he chose not to work for the government. Instead, he managed his family's properties and gave a lot of his time and money to help others. People called him "the Father of the Poor."

When he was 27, he accepted the teachings of the Báb, who was a new prophet. Baháʼu'lláh became a strong supporter of this new religion, which taught that some old laws should change. This made many people angry. When he was 33, the government tried to stop the Bábí movement. Baháʼu'lláh almost died, his properties were taken, and he was sent away from Iran. While he was in a dungeon called the Síyáh-Chál, Baháʼu'lláh said he received messages from God. This was the start of his special mission.

After moving to Iraq, Iranian leaders still wanted him moved further away. So, the Ottoman government sent him to Istanbul. There, he was put under house arrest in Edirne for four years, and then spent two very hard years in the prison-city of ‘Akká. Slowly, his freedom increased, and he spent his last years living more freely near ‘Akká.

Baháʼu'lláh wrote at least 1,500 letters, some as long as books. These have been translated into over 800 languages. Some of his famous writings include The Hidden Words, the Book of Certitude, and the Kitáb-i-Aqdas. Some of his teachings are about spiritual things, like the nature of God and how the soul grows. Others are about how society should work, what his followers should do, and how the Baháʼí Faith should be organized. He believed that humans are spiritual beings. He asked everyone to develop good qualities and help society grow, both spiritually and physically.

Baháʼu'lláh died in 1892 near ‘Akká. His burial place is a special spot for his followers, called Baháʼís, to visit. Today, there are between 5 and 8 million Baháʼís living in 236 countries. Baháʼís believe Baháʼu'lláh is a messenger or Manifestation of God, just like Buddha, Jesus, and Muhammad.

Contents

Understanding Baháʼu'lláh's Name

Baháʼu'lláh (pronounced ba-HA-ul-LAH) is a special title that means "Glory of God." His birth name was Ḥusayn-ʻAlí. Because his father was a nobleman from the region of Núr, he was also known as Mírzá Ḥusayn-ʻAlí Núrí. In 1848, he chose the title Baháʼ, which means "glory" or "splendour" in Arabic.

Many things in the Baháʼí Faith are connected to the word Baháʼ. For example, a nine-pointed star or nine-sided temples are linked to the number value of Baháʼ. The word Baháʼí means a follower of Baháʼ. His son, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, chose his title (which means "Servant of Baháʼ") to show his devotion to Baháʼu'lláh.

Baháʼu'lláh's Early Life in Iran

Baháʼu'lláh was born in Tehran, Iran, on November 12, 1817. Baháʼí writers say his family tree goes back to important figures like Abraham, Zoroaster, and King David. His father, Mírzá ʻAbbás-i-Núrí (also known as Mírzá Buzurg), was an important official in the government.

Baháʼu'lláh married Ásíyih Khánum in Tehran in 1835. He was 18 and she was 15. Even though he came from a privileged family, Baháʼu'lláh chose to spend his time and money on helping the poor. People knew him as "the Father of the Poor."

Accepting the Báb's Message

In May 1844, a young merchant named Siyyid Mírzá ʻAlí-Muḥammad from Shiraz, Iran, announced that he was a new prophet from God. He took the title "the Báb" (meaning "the gate"). He said he was preparing the way for an even greater teacher from God who would appear soon.

The Báb sent a special message to Baháʼu'lláh. When Baháʼu'lláh received it at age 27, he immediately believed the Báb's message was true. He began sharing it with others. Because he was well-known, many people, including Muslim leaders, became interested in the new religion. His home in Tehran became a center for Bábí activities, and he gave a lot of money to support the faith.

In 1848, Baháʼu'lláh attended a meeting called the Conference of Badasht. At this meeting, important discussions happened about whether the Báb's teachings meant a new religion had begun. Baháʼu'lláh helped everyone agree that it was indeed a new religious path. It was at this meeting that he took the name Baháʼ.

The Bábí Faith quickly grew in Persia. This made many Islamic leaders and government officials worried. Thousands of Bábís were killed in terrible persecutions. In July 1850, the Báb himself was executed by firing squad at age 30.

The Báb taught that he was the first of two special messengers from God. These messengers would bring about lasting peace and unity for all humanity. Baháʼís believe the Báb's teachings prepared the world for a society where nations are united, religions are friendly, and all people have equal rights. The Báb often spoke of "Him whom God shall make manifest", the great Promised One who would appear soon after his own death.

Arrest and Imprisonment

After the Báb's execution, things were very difficult for Bábís. Many were killed. On August 15, 1852, two young Bábís tried to assassinate the Iranian king, whom they blamed for the killings. The king was not seriously hurt, but this led to even worse persecution against Bábís.

Even though investigations showed Baháʼu'lláh was not involved in the assassination attempt, he was arrested. He was put in a dark, underground prison in Tehran called the Síyáh-Chál. He was chained with heavy chains that left scars on him for the rest of his life. Baháʼu'lláh was held there for four months.

A Divine Revelation

While in the Síyáh-Chál, Baháʼu'lláh said he had several spiritual experiences. He felt that he received his mission as a messenger of God, the Promised One the Báb had spoken about. Baháʼís believe this moment marked the beginning of the fulfillment of the Báb's prophecies. Because the Báb and Baháʼu'lláh's missions are seen as connected, Baháʼís consider the Báb's declaration in 1844 as the start date of the Baháʼí Faith.

Sent Away from Persia

When it was clear Baháʼu'lláh was innocent, the king agreed to free him. But he ordered Baháʼu'lláh to leave Persia forever. In January 1853, during a very cold winter, Baháʼu'lláh and his family began a three-month journey to Baghdad. This was the start of his exile, which lasted the rest of his life in lands belonging to the Ottoman Empire.

Life in Exile

In Baghdad

In Baghdad, Baháʼu'lláh began sending messages and teachers to encourage the Bábís in Persia, who were still being persecuted. Many Bábís moved to Baghdad to be near him. One of them was Mirza Yahya, Baháʼu'lláh's younger half-brother. Baháʼu'lláh had largely taken care of Yahya's education after their father died.

For a while, Yahya worked as Baháʼu'lláh's secretary. But he became jealous of the growing respect Bábís showed Baháʼu'lláh. Yahya tried to become the leader of the Bábí religion. He claimed a letter from the Báb meant he was the Báb's successor. However, other Bábí writings clearly said there would be no successor. Yahya also spread false rumors about Baháʼu'lláh.

Journey to Kurdistan

To avoid arguments and protect the unity of the Bábí community, Baháʼu'lláh left Baghdad quietly on April 10, 1854. He went to the mountains of Kurdistan. He lived there as a hermit, dressed as a dervish, and used a different name.

In Kurdistan, Baháʼu'lláh became known for his wisdom and knowledge. Religious leaders sought his advice. One of his books, the Four Valleys, was written for one of these leaders.

While Baháʼu'lláh was away, Mirza Yahya's true character became clear. He failed to guide the Bábí community and tried to gain power for himself. He even encouraged some followers to kill other Bábís he saw as rivals. Yahya's actions made most Bábís reject his claims.

When Baháʼu'lláh's friends in Baghdad heard rumors of a wise person in Kurdistan, they suspected it was him. They asked him to return to help the community. Baháʼu'lláh agreed and returned to Baghdad on March 19, 1856.

Return to Baghdad

For the next seven years, Baháʼu'lláh worked to strengthen the Bábí community. He set a good example and constantly interacted with Bábís. More and more people joined the revived Bábí movement. Princes, scholars, and government officials came to meet him. This made the Iranian government and some religious leaders nervous again.

Invitation to Constantinople

The Persian government asked the Ottoman government to send Baháʼu'lláh back to Persia, but they refused. Instead, the Persians pushed the Ottomans to move Baháʼu'lláh away from Baghdad, which was too close to Iran. So, in April 1863, Sultan ʻAbdu'l-ʻAzíz invited Baháʼu'lláh to live in the Ottoman capital, Constantinople (now Istanbul).

First Public Announcement

On April 22, 1863, Baháʼu'lláh left his house in Baghdad and went to the Najibiyyih garden-park across the Tigris river. He stayed there for twelve days with his family and a few close followers. In this garden, Baháʼu'lláh told his companions that he was "Him whom God shall make manifest", the one promised by the Báb. He announced that his mission as God's latest messenger had begun. This garden is now known as the Garden of Riḍván, and the twelve days are celebrated by Baháʼís as the Festival of Riḍván.

Time in Constantinople

Baháʼu'lláh left the Riḍván garden on May 3, 1863, and traveled to Constantinople with his family and companions. He arrived on August 16, 1863. Government ministers and important people welcomed him.

It was common for important guests to visit government officials to ask for favors. But Baháʼu'lláh did not visit anyone. He said he had no demands or favors to ask. This independence was used by the Persian ambassador to spread false stories about Baháʼu'lláh to the Ottoman court. As a result, less than four months after arriving, the Sultan ordered Baháʼu'lláh and his companions to be sent to Adrianople (now Edirne).

Sent to Adrianople

On December 12, 1863, Baháʼu'lláh arrived in Adrianople. He stayed there for four and a half years. This was an important time for his mission. He sent many writings to Bábís in Iran, and most of them came to recognize him as the leader of their faith.

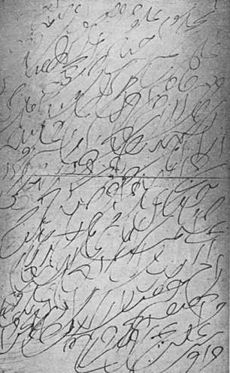

Mirza Yahya, Baháʼu'lláh's half-brother, tried again to become the leader. He even tried to poison Baháʼu'lláh, which caused Baháʼu'lláh to be very sick for a month and left him with a hand tremor. Yahya also tried to get Baháʼu'lláh's bath attendant to assassinate him. These actions caused great trouble among the Bábís.

Baháʼu'lláh had always been kind to Yahya, but after these events, he decided it was time to clearly declare his spiritual station to Yahya. In March 1866, Baháʼu'lláh sent a letter to Yahya, stating that he was God's latest messenger, the Promised One of the Báb. He asked Yahya to accept and support him. Yahya, however, claimed that he was the promised messenger.

This led to a clear split. Almost all Bábís in Adrianople, and later in Persia and Iraq, chose to follow Baháʼu'lláh. They understood that the Báb's teachings required them to accept the Promised One when he appeared. From this time on, those who followed Baháʼu'lláh began to call themselves "Baháʼís" (meaning "the people of Baháʼ").

Final Exile and Imprisonment in ‘Akká

Mirza Yahya continued to try to discredit Baháʼu'lláh with the Ottoman authorities. He accused Baháʼu'lláh of causing trouble. The government investigated and found Baháʼu'lláh innocent. However, to prevent future problems, the Ottomans decided to imprison both Baháʼu'lláh and Mirza Yahya in distant parts of their empire. In July 1868, Baháʼu'lláh and his family were sentenced to lifelong imprisonment in the harsh prison-city of ʻAkká. Mirza Yahya was sent to prison in Famagusta, Cyprus.

Baháʼu'lláh and his companions arrived in ‘Akká on August 31, 1868, and were put in the city's prison. The first few years were very difficult, and many Baháʼís became sick. In June 1870, Baháʼu'lláh's 22-year-old son, Mirzá Mihdí, died after falling from the prison roof while praying.

Over time, conditions improved. Baháʼu'lláh and his family were moved out of the prison. Eventually, after the Sultan's death, Baháʼu'lláh was allowed to leave the city and live in the surrounding areas. From 1877 to 1879, he lived in Mazra'ih, a house a few miles north of ‘Akká.

Even though he was still officially a prisoner, Baháʼu'lláh spent his final years (1879–1892) in the Mansion of Bahjí, just outside ‘Akká. He spent his time writing many books about his teachings, including his vision for a united world and the importance of good actions and prayers.

Baháʼu'lláh died on May 29, 1892, in Bahjí. He was buried next to the mansion in a building that is now his shrine. This is a very important place for Baháʼís from all over the world. In 2008, the shrine and other Baháʼí holy places in ‘Akká and Haifa were added to UNESCO's list of World Heritage Sites.

Baháʼu'lláh's Teachings

About God

The Baháʼí Faith teaches that there is only one God. God is the creator of everything and has always existed. Baháʼu'lláh taught that God is "unknowable" and "inaccessible" to humans. This means we can never fully understand God. However, God gave humans the ability to know that God exists and to develop spiritual qualities like love, mercy, kindness, and justice.

God's Messengers

Baháʼu'lláh explained that humans can only know God through special beings called Manifestations of God. These are not just wise people; they are spiritual beings sent by God to guide humanity. Baháʼís believe that these Manifestations are like perfect mirrors reflecting the light of one sun. Each mirror is different, but the reflection is always from the same sun.

Baháʼís see each major world religion as part of one educational process from God. This process has helped human civilization grow by teaching people to unite in larger and larger groups—from families to tribes, then cities, and now nations. Eventually, humanity will unite as one global family.

Baháʼu'lláh called this a "progressive Revelation". He said that every divine teacher makes a promise to their followers about the next messenger God will send. This promise is found in the holy books of all religions. Followers of each religion have a duty to carefully investigate if a new messenger truly fulfills the prophecies.

Fulfilling Prophecies

When Baháʼu'lláh announced his mission, he also declared that he was the Promised One mentioned in the holy books of every major religion. Baháʼís understand this to mean a spiritual fulfillment of prophecies, not always a literal one. This is based on Baháʼu'lláh's teachings about the oneness of God's messengers and the oneness of religion.

So, Baháʼís believe Baháʼu'lláh fulfills prophecies for Jews as the "Everlasting Father" and "Prince of Peace"; for Christians as the "Spirit of Truth" and Christ returned; for Muslims as the return of important figures; for Zoroastrians as the promised Shah-Bahram; for Hindus as the reincarnation of Krishna; and for Buddhists as Maitreya, the fifth Buddha.

How to Live Rightly

Baháʼu'lláh asked every Baháʼí to live a good, healthy, and productive life. He taught the importance of good manners and moral virtues like truthfulness, honesty, patience, kindness, and justice. He encouraged believers to be friendly with people of all faiths. He strongly condemned all forms of religious violence.

Baháʼu'lláh taught that true religion helps prevent crime, keeps society in order, and helps people grow spiritually. He said it's important to work in a job or profession to benefit yourself and others. Baháʼís are asked to be good, honest, and loyal citizens wherever they live. They should avoid pride, arguments, and gossip. Baháʼu'lláh's main message is to serve humanity and work with others to unite the world.

Social Principles

Baháʼu'lláh said his message is for all people, and its goal is to build a new, united world. He taught the principle of the oneness of mankind. He urged world leaders to work together to solve problems and achieve peace through collective security. To build a united world, he stressed the importance of ending religious and racial prejudice and avoiding extreme nationalism. He also said that the rights of all minorities must be protected.

A key condition for global peace is complete equality between women and men. Baháʼu'lláh stated that God sees both sexes as equal. To achieve this, Baháʼí teachings call for big changes in society, including ending discrimination against women and focusing more on educating girls so women can reach their full potential.

Leadership and the Covenant

In his will, called the "Book of My Covenant", Baháʼu'lláh clearly named his eldest son, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, as his successor. He made ʻAbdu'l-Bahá the only person authorized to explain his writings and the perfect example of his teachings. This was to provide clear guidance and keep the Baháʼí Faith united. Most Baháʼís easily accepted ʻAbdu'l-Bahá because he had always shown great ability and devotion to his father.

Baháʼu'lláh's Covenant also set up a system to guide and protect the growing Baháʼí community. Baháʼís believe this Covenant is what keeps their Faith united and prevents it from splitting into different groups, which has happened in older religions after their founders died. To this day, the Baháʼí Faith remains undivided.

Baháʼí Administration

Baháʼí communities around the world are managed using principles of discussion and group decision-making. There are no clergy (like priests or ministers) in the Baháʼí Faith. No individual Baháʼí can tell another what to think or do. Baháʼu'lláh encouraged Baháʼís to share his teachings, but he forbade trying to force people to convert.

Working in groups and being involved in the community are important parts of Baháʼí life. Activities are guided by nine-member councils, elected every year. These councils operate at local, regional, and national levels. All Baháʼí projects are supported by money given voluntarily by Baháʼís only. Baháʼí council members and those who help with community activities (like moral education classes for children) serve without pay. The worldwide Baháʼí administration is led by the Universal House of Justice. This global council is elected every five years by Baháʼís from around the world.

Baháʼu'lláh's Writings

How They Were Written

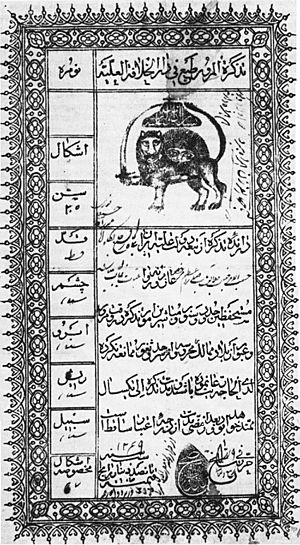

Baháʼís believe all of Baháʼu'lláh's writings are divinely revealed, even those written before he announced his mission. Sometimes he wrote himself, but usually he spoke the words aloud to a secretary. He sometimes spoke so fast that it was hard for the secretary to write everything down. Most of Baháʼu'lláh's writings are short letters, called tablets, sent to one or more people.

Some of his longer works include the Hidden Words, the Seven Valleys, the Book of Certitude, the Kitáb-i-Aqdas (Most Holy Book), and the Epistle to the Son of the Wolf. His original writings are in Persian and Arabic. His complete works are more than 100 volumes long, with about 15,000 identified and confirmed items.

What They Are About

His writings cover many topics related to human life, for both individuals and groups. They include comments on holy scriptures and prophecies, new laws for this time, mystical writings, explanations about God, and descriptions of how human souls are noble and can know God. He also wrote about life after death and how souls grow forever. He taught that work done to serve others is a form of worship.

Baháʼu'lláh also explained how to have fair government and create unity and world order. He wrote about knowledge, philosophy, and healthy living. He called for universal education and living virtuously. He also wrote many prayers and meditations.

Letters to World Leaders

Baháʼu'lláh wrote many letters to kings, rulers, and religious leaders. In these letters, he said he was the Promised One mentioned in the Torah, the Gospels, and the Qur’an. He asked them to accept his message, give up their love for material things, rule fairly, protect the weak, reduce their weapons, solve their disagreements, and work together to improve the world and unite its people. He warned that the old world was ending and a new global civilization was beginning.

In these letters, Baháʼu'lláh also suggested ways to create a sense of global community. These included creating an international language, universal public education, and a common global currency. He urged rulers to cut military spending, create an international court to settle disputes, use taxes for social benefits, and follow democratic principles. He advised religious leaders to study his cause openly, give up political power, and end meaningless rituals. He also told monks to mix with people and serve the community.

These letters were sent to leaders like Czar Alexander II of Russia, Francis Joseph I of Austria-Hungary, Napoleon III of France, Nasiri’d-Din Shah of Persia, Pope Pius IX, Queen Victoria of Great Britain, Ottoman Sultan ʻAbdu’l-ʻAzíz, and Wilhelm I of Prussia. He also wrote to the rulers and presidents of America, elected representatives, and religious leaders everywhere.

While these leaders did not respond much, Baháʼu'lláh's letters gained attention because his warnings to Napoleon, the Pope, Kaiser Wilhelm, and others about their downfalls or losses came true.

Voice in His Writings

Baháʼu'lláh explained that each messenger of God has two sides: one connected to God and one connected to this world. He said that all messengers are guided by God to use their words to touch human hearts and souls, so people can understand the truths they are sharing.

The "voice" in Baháʼu'lláh's writings changes depending on the topic or who he is writing to. Sometimes he speaks like a caring friend, sometimes like someone passing on a message from the messenger, sometimes as if God is speaking directly, and sometimes with great humility before God. The voice can even change within one text, or be a conversation, like in the Fire Tablet or the Tablet of Carmel. No matter the style, the goal is always to share spiritual truths.

Collecting and Translating Writings

The Baháʼí World Centre works to collect, confirm, organize, and protect Baháʼu'lláh's original writings. Through a worldwide program, his writings are now available in over 800 languages.

Photographs of Baháʼu'lláh

There are two known photographs of Baháʼu'lláh, both taken in Adrianople. Copies are kept at the Baháʼí World Centre. One picture is shown to Baháʼís during special visits to the International Archives building as part of their pilgrimage.

Baháʼís generally do not display photographs of Baháʼu'lláh in public or in their homes. They also prefer that others avoid showing them in books and on websites. This practice applies to images of any Manifestation of God.

See also

In Spanish: Baha'ullah para niños

In Spanish: Baha'ullah para niños

- History of religion

- History of the Baháʼí Faith

- Apostles of Baháʼu'lláh

- List of Baháʼís

- Baháʼí Faith by country