Báb facts for kids

Quick facts for kids The Báb |

|

|---|---|

Shrine of the Báb in Haifa, Israel

|

|

| Religion | Bábism |

| Personal | |

| Nationality | Persian |

| Born | ʿAli Muhammad October 20, 1819 Shiraz, Iran |

| Died | July 9, 1850 (aged 30) Tabriz, Iran |

| Cause of death | Execution by firing squad |

| Resting place | Shrine of the Báb 32°48′52″N 34°59′14″E / 32.81444°N 34.98722°E |

| Spouse | Khadíjih-Sultán (1842–1850) |

| Children | Ahmad (1843–1843) |

| Parents | Mirzá Muhammad Ridá (father) Fátimih Bagum (mother) |

| Senior posting | |

| Title | The Primal Point |

The Báb (born ʿAlí Muḥammad; 20 October 1819 – 9 July 1850) was a special spiritual leader. He founded a religion called Bábism and is also a very important person in the Baháʼí Faith. He was a merchant from Shiraz, a city in Qajar Iran (which is now Iran). In 1844, when he was 25, he announced that he was a messenger from God.

He chose the title Báb, which means "Gate" or "Door" in Arabic. This name hinted at his role as a link to a hidden spiritual leader. He started a new religious movement that suggested changing old Islamic laws and traditions to create a new way of life. Many ordinary people liked his ideas, but some religious leaders and the government were against him.

The Báb wrote many letters and books. In these writings, he shared ideas for a new society and promised that another divine messenger would come soon. He encouraged people to learn about arts and sciences. He also set rules for things like marriage, divorce, and inheritance, though these rules were never fully put into practice. Even though there were some conflicts between his followers (called Bábís) and the government, the Báb taught his followers to be peaceful. He told them not to force anyone to join their faith.

The Báb was executed for his beliefs. He was tied up in a public square in Tabriz and faced a firing squad. Many people watched this event. After the first shots, he mysteriously disappeared, only to reappear and be shot again. This surprising event made even more people curious about his message. His body was secretly kept safe and moved many times. Finally, in 1909, his remains were buried in a beautiful shrine built by ʻAbdu'l-Bahá on Mount Carmel in Israel.

For followers of the Baháʼí Faith, the Báb is like John the Baptist in Christianity or Elijah in Judaism. He was a special person who prepared the way for their own religion. The Baháʼí Faith, which has millions of members today, believes that Baháʼu'lláh (its founder) was the new messenger the Báb had promised. Most Bábís became Baháʼís by the end of the 1800s.

Contents

The Báb's Early Life

Growing Up in Shiraz

The Báb's full name was Siyyid ʿAlí Muḥammad Shírází. He was born on October 20, 1819, in Shiraz, Iran. His family were middle-class merchants. He was a descendant of Muhammad, an important figure in Islam. His father passed away when he was very young, so his maternal uncle, Hájí Mírzá Siyyid ʿAlí, raised him.

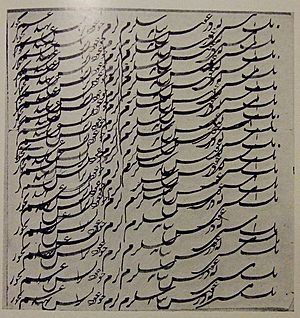

In Shiraz, his uncle sent him to a primary school called a maktab. He studied there for about six or seven years. Unlike the usual school lessons of the time, which focused on religious law, the Báb was more interested in subjects like mathematics and beautiful writing (calligraphy). He also felt a strong connection to spiritual things. His teachers didn't always like his creative and imaginative mind. The Báb later taught that children should be treated with respect, allowed to play, and never be yelled at by their teachers.

When he was between 15 and 20 years old, he joined his uncle's family business. He became a merchant in the city of Bushehr, near the Persian Gulf. He was known for being very honest and trustworthy in his business, which involved trading with countries like India and Oman. Some of his early writings show that he didn't really enjoy business. Instead, he preferred to study religious books.

Marriage and Family Life

In 1842, when he was 23, the Báb married Khadíjih-Sultán Bagum. She was 20 and came from a well-known merchant family in Shiraz. Their marriage was a happy one. They had one son named Ahmad, but he sadly passed away the same year he was born (1843). Khadijih never had another child. The young couple lived in a simple house in Shiraz with the Báb's mother. Khadijih later became a follower of the Baháʼí Faith.

The Shaykhi Movement

In the late 1700s, a religious teacher named Shaykh Ahmad started a new way of thinking within Shia Islam. His followers, called Shaykhis, believed that a special spiritual leader, the Mahdi, would soon appear. They also believed that the world's end and resurrection were more spiritual than physical. Shaykh Ahmad's ideas were different from what most religious leaders taught, and he was sometimes criticized.

After Shaykh Ahmad died, his student Kazim Rashti became the leader. He focused on the year 1844, believing it was when the Mahdi would appear. In 1841, the Báb visited Karbala in Iraq and attended Kazim Rashti's lectures. When Kazim Rashti died in 1843, he told his followers to search for the Mahdi. One of these followers, Mullá Husayn, traveled to Shiraz and met the Báb.

The Báb's Personality

People who knew the Báb often described him as gentle, very smart, and gifted. One follower said he was "very quiet" and only spoke when necessary. He was always thinking deeply and praying. He was described as a handsome man with a thin beard, who dressed neatly and had a soft, pleasant voice.

An Irish doctor who met him said he was "a very mild and delicate-looking man, rather small... with a melodious soft voice." Shoghi Effendi, a later Baháʼí leader, praised the Báb for being "matchless in His meekness, imperturbable in His serenity, magnetic in His utterance." His kind and calm personality attracted many people.

The Báb as a Religious Leader

The Báb's journey as a religious leader began with a dream. After this dream, he felt inspired to write his own verses and prayers, believing they came from God. In April 1844, his wife Khadijih was the first to believe in his special message.

Meeting Mullá Husayn

The Báb's first public step as a spiritual leader happened when Mullá Husayn arrived in Shiraz. On the evening of May 22, 1844, the Báb invited Mullá Husayn to his home. Mullá Husayn explained he was looking for the promised leader who would follow Kazim Rashti. The Báb then told Mullá Husayn that he was that promised leader and had special divine knowledge.

Mullá Husayn became the first person to accept the Báb's claims. The Báb answered all of Mullá Husayn's questions and quickly wrote a long explanation of a chapter from the Qur'an. This writing, called the Qayyúmu'l-Asmáʼ, is considered the Báb's first revealed work. It is now a special holy day for Baháʼís.

The Letters of the Living

Mullá Husayn was the Báb's first follower. Within five months, seventeen other students of Kazim Rashti also believed the Báb was a special messenger from God. One of them was a woman named Fátimih Zarrín Táj Barag͟háni, a poet, who later became known as Táhirih, "the Pure." These 18 followers became known as the Letters of the Living.

Their job was to spread the Báb's new faith across Iran and Iraq. The Báb said these 18 people, along with himself, formed the first "Unity" of his religion. This group of 19 was very important in the early days of Bábism.

Travels and Imprisonment

After the Letters of the Living accepted him, the Báb and one of his followers, Quddús, went on a pilgrimage to Mecca and Medina, the holy cities of Islam. In Mecca, the Báb publicly announced his mission. After their pilgrimage, the Báb and Quddús returned to Bushehr.

Quddús's travels to Shiraz made the governor, Husayn Khan, aware of the Báb's claims. The governor had Quddús tortured and ordered the Báb to come to Shiraz in June 1845. The Báb was questioned by religious leaders. At first, he seemed to deny some of his claims, perhaps to avoid immediate execution. He was then placed under house arrest at his uncle's home.

In September 1846, a cholera outbreak allowed him to leave Shiraz. He went to Isfahan, where many people came to see him. His popularity grew after he debated local clergy and showed how quickly he could write inspired verses. However, after the governor of Isfahan, who supported him, died, the Báb was ordered to Tehran in January 1847. Before he could meet the Shah, the Prime Minister sent him to Tabriz for confinement.

After 40 days in Tabriz, the Báb was moved to the fortress of Maku, near the Turkish border. While imprisoned there, the Báb began writing his most important work, the Persian Bayán, which he did not finish. Because his popularity grew even in Maku (even the governor became a follower), the Prime Minister moved him again to the fortress of Chihríq in April 1848. There, too, the Báb's popularity increased, and his jailers became less strict.

Trial in Tabríz

In June 1848, the Báb was brought from Chihríq to Tabríz for a trial. He faced a group of Islamic clergy who accused him of abandoning his religion. On the way, he spent 10 days in Urmia, where the only known portrait of him was made.

The trial took place in July 1848, with the Crown Prince present. The clergy questioned the Báb about his claims and teachings. They asked him to perform miracles and to take back his statements. There are several eyewitness accounts of the trial. In one answer, the Báb stated, "I am that person you have been awaiting for one thousand years."

The trial did not have a clear outcome. Some clergy wanted him executed, but the government wanted a milder judgment because the Báb was popular. The government even asked doctors to say the Báb was mentally unwell to prevent his execution. The Crown Prince's doctor, William Cormick, examined the Báb and agreed, which saved him from execution for a while. However, the clergy insisted on a physical punishment, so the Báb received 20 lashes to the bottoms of his feet.

An official government report, unsigned and undated, claimed that the Báb later took back his claims in writing and apologized. Some historians believe this document was created by the authorities to embarrass the Báb and make people lose faith in him. They say the writing style is very different from the Báb's usual way of writing. Despite pressure, the Báb stood firm in his beliefs. After the trial, the Báb was sent back to the fortress of Chehríq.

His Proclamation

In his early writings (1844-1847), the Báb seemed to identify himself as a "gate" or "door," referring to a link to the Hidden Imam. In his later writings, the Báb more clearly stated that he was the Hidden Imam himself and a new messenger from God.

The Báb's different claims were understood in various ways. Some critics say his claims changed over time, but his supporters believe he gradually revealed his true identity in a careful way. For example, the Báb's first writing was similar to the Qur'an, which people at the time would have recognized as a claim to divine revelation.

Some scholars suggest that the Báb initially claimed a lower position to avoid being persecuted and imprisoned. A public announcement of being the Mahdi could have led to immediate death. This careful approach helped him gain attention without too much controversy in the early stages.

However, this gradual way of revealing his claims caused some confusion among the public and even some of his followers. Some early believers saw him as a messenger with divine authority, which led to disagreements within the Bábí community. Even though the Báb wanted to share his message carefully, many of his followers, like Táhirih, openly declared the coming of the promised Hidden Imam.

The Báb's Execution

In mid-1850, a new prime minister, Amir Kabir, ordered the Báb's execution. This was likely because Bábí uprisings had been defeated, and the movement's popularity seemed to be decreasing. The Báb was brought back to Tabriz from Chehriq to be executed by a firing squad. The night before his execution, a young Bábí named Muhammad-Ali (Anis) asked to die with him. He was arrested and placed in the same cell as the Báb.

On the morning of July 9, 1850, the Báb was taken to the courtyard of the barracks. Thousands of people gathered to watch. The Báb and Anis were hung on a wall, and a large group of soldiers prepared to shoot. Many eyewitnesses, including Western diplomats, described what happened. When the order was given to fire, the first shots did not kill the Báb. Instead, the bullets cut the rope holding them to the wall.

A second firing squad was brought in, and a second order to fire was given. This time, the Báb was killed. In Bábí and Baháʼí tradition, the failure of the first shots to kill the Báb is seen as a miracle. The bodies of the Báb and Anis were thrown into a ditch.

However, a few Bábís secretly rescued the remains and hid them. Over time, the remains were secretly moved according to instructions from Baháʼu'lláh and then ʻAbdu'l-Bahá. They traveled through many cities until they reached Acre (now in Israel) in 1899. On March 21, 1909, the remains were buried in a special tomb, the Shrine of the Báb, built by ʻAbdu'l-Bahá on Mount Carmel in Haifa, Israel. The Baháʼí World Centre is located nearby and welcomes visitors to its beautiful gardens.

The Báb's Teachings and Legacy

The Báb's ideas were influenced by the Shaykhism movement. His writings often used a lot of symbolism and calculations based on numbers.

The Báb's teachings developed in three main stages. His earliest teachings focused on explaining the Quran and hadith (sayings of Muhammad), showing how his ideas fit with "true Islam." He emphasized the deeper, spiritual meanings of religious laws. Later, his teachings became more philosophical, explaining things like how to understand spiritual truth and the nature of human beings. Finally, his writings included new laws and clearly stated the idea of Progressive Revelation, meaning God sends new messages over time.

In 1848, the Báb's teachings changed, and he introduced his own set of laws, replacing some Islamic ones. These laws covered marriage, burial, prayer, and other practices. They seemed designed for a future Bábí society or to be put into action by "Him Whom God shall make manifest" – a future prophet he mentioned often in his writings.

The Báb greatly improved the status of women in his teachings. He taught that since God is beyond male and female, neither men nor women should feel superior to each other. He told his followers never to mistreat women and set a higher penalty for causing sadness to women than to men. He also encouraged education for women and made no gender differences in Bábí laws about learning. In 19th-century Iran, these ideas were very revolutionary. The Báb also described God's will as a female figure, "the maid of heaven."

The Báb also thought about how news should be shared. He stressed the need for a fast news system that everyone could use, no matter how rich or poor they were. He wrote that until such a system was available to all, its benefits wouldn't reach everyone.

Some scholars say the Báb's writings predicted current global issues, like protecting the environment and how natural resources are used. In his Persian Bayán, he specifically called for water to be absolutely pure. This can be seen as a general rule for protecting the environment. His Arabic Bayán also said that the four elements – earth, air, fire, and water – should not be bought and sold like goods.

The Báb's religious teachings included ideas common in some earlier Shiʿi groups, like the belief that God's true nature is unknowable. This idea continued to be a key principle in the Baháʼí Faith.

The Báb also developed a unique philosophy of beauty. He believed that beauty and refinement should guide not only art but also our actions. He stressed the need to bring everything to its highest state of perfection. He wrote that if someone knows how to make something more beautiful but doesn't, they are holding back grace and favor.

Who Came After the Báb?

In most of his important writings, the Báb spoke about a Promised One, often called man yazhiruhu'lláh, "Him Whom God shall make manifest". He said he himself was "but a ring upon the hand of Him Whom God shall make manifest." Within 20 years of the Báb's death, more than 25 people claimed to be this Promised One. The most important of these was Baháʼu'lláh.

Before the Báb died, he sent a letter to Mírzá Yahyá, also known as Subh-i-Azal. Some people consider this his will. It named Subh-i-Azal as the leader of the Bábí community after the Báb's death and told him to obey the Promised One when he appeared. At that time, Subh-i-Azal was still a teenager and lived with his older brother, Baháʼu'lláh. Baháʼís believe the Báb appointed Subh-i-Azal to draw attention away from Baháʼu'lláh, protecting him from danger.

In 1852, while imprisoned in Tehran, Baháʼu'lláh had a spiritual experience that marked the beginning of his mission as a Messenger of God. Eleven years later, in Baghdad, he publicly announced his claim. Most Bábís eventually recognized Baháʼu'lláh as "Him Whom God shall make manifest." His followers then began calling themselves Baháʼís.

Subh-i-Azal's followers were called Azalis. For Bábís who did not accept Baháʼu'lláh, Subh-i-Azal remained their leader until his death in 1912. Today, the Baháʼí Faith has millions of followers, while the number of Azalís is very small, perhaps around one thousand in Iran.

Baháʼí Commemorations

In the Baháʼí calendar, the birth, declaration, and death of the Báb are celebrated by Baháʼí communities every year. These are special Baháʼí Holy Days.

The idea of "twin Manifestations of God" is a key belief in the Baháʼí Faith. It describes the relationship between the Báb and Baháʼu'lláh. Both are seen as special messengers from God who founded their own religions (Bábism and the Baháʼí Faith) and revealed their own holy books. However, Baháʼís believe the Báb's mission was to prepare the way for Baháʼu'lláh. They compare Baháʼu'lláh and the Báb to Jesus and John the Baptist. Both the Báb and Baháʼu'lláh are highly respected figures in the Baháʼí Faith.

The Báb's Impact

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, a leader of the Baháʼí Faith, summarized the Báb's impact: "Alone, He undertook a task that can scarcely be conceived... This illustrious Being arose with such power as to shake the foundations of the religious laws, customs, manners, morals, and habits of Persia, and instituted a new law, faith, and religion." The Báb has been compared to Martin Luther, who also brought about major religious changes.

The Bábí movement had a big influence on religious and social thinking in 19th-century Iran.

The Báb's Writings

The Báb said that the verses revealed by a Manifestation of God are the best proof of their mission. The Báb's writings include over two thousand tablets, letters, prayers, and philosophical essays. These writings are part of Baha'i scripture, and his prayers are often recited by Baháʼís. Scholars are also very interested in studying the Báb's works.

One scholar, Elham Afnan, said the Báb's writings "restructured the thoughts of their readers, so that they could break free from the chains of obsolete beliefs and inherited customs." Another scholar, Jack McLean, noted that the Báb's writings are full of symbols. Numbers, colors, minerals, and even parts of the human body are used to reflect deeper spiritual meanings. The Báb's works also use new words and phrases when existing religious terms were not enough. Some parts of his writings are like a "stream of consciousness," flowing freely.

The Báb himself divided his writings into five types: divine verses, prayers, commentaries, logical discussions (in Arabic), and a Persian style that included all four. Scholars have also noticed that certain important religious words or phrases are repeated often throughout his writings.

Most of the Báb's writings have been lost. He himself said they were more than five hundred thousand verses long. To compare, the Qur'an is about 6,300 verses long. If each page had 25 verses, that would be 20,000 pages of text! For example, nine complete commentaries on the Qur'an that the Báb revealed while imprisoned in Maku are now lost.

Many of his works were written in response to specific questions from his followers. This was a common way for important religious texts to be created, similar to how many parts of the New Testament are letters. Sometimes, the Báb would reveal works very quickly by chanting them while a secretary and witnesses were present.

The Archives Department at the Baháʼí World Centre currently has about 190 of the Báb's Tablets. Parts of his main works have been published in English in a book called Selections from the Writings of the Báb.

The Báb has been criticized for sometimes using incorrect Arabic grammar in his religious works, although his Arabic letters had very few mistakes. One reason for this might have been to help people focus on the deeper meaning of his message rather than just the outer form of the words. In his Treatise on Grammar, the Báb said that Arabic grammar should be taught as an outer symbol of the spiritual grammar of the universe.

Important Early Writings (Before and During his Declaration)

- The Báb started his Tafsir on Surah al-Baqara in late 1843, before he declared his mission. The first half was finished by early 1844, and the second half after his declaration. It is the only work from before his declaration that still exists completely.

- The first chapter of the Qayyúmu'l-Asmáʼ was written by the Báb on the evening of May 22, 1844, when he declared his mission to Mullá Husayn. The whole work, which is hundreds of pages long, took 40 days to write. It was widely shared in the early days of the Bábí movement and was like a holy book for them. In it, the Báb stated his claim to be a Manifestation of God, though sometimes he also said he was a servant of the Hidden Imám.

- Sahífih-yi-makhzúnih was revealed before he left for Mecca in September 1844. It is a collection of 14 prayers, mostly for specific holy days. Its content was still within the usual expectations of Islam at that time.

Writings During Pilgrimage (1844–1845)

While on his pilgrimage to Mecca, the Báb wrote many works:

- Khasá'il-i-sabʿih: This work was written on his sea journey back to Bushehr. It listed some rules for the Bábí community.

- Kitáb-i-Rúḥ ("Book of the Spirit"): This book contains many verses and was written while the Báb was sailing.

- Sahífih baynu'l-haramayn ("Treatise Between the Two Sanctuaries"): This Arabic work was written while the Báb traveled from Mecca to Medina. It answered questions from a well-known Shaykhí leader.

- Kitáb-i-Fihrist ("The Book of the Catalogue"): This is a list of the Báb's own works, written by him after he returned from pilgrimage in June 1845. It is a bibliography of his earliest writings.

Writings from Bushehr and Shiraz (1845–1846)

The Báb was in Bushehr from March to June 1845, then in Shiraz.

- Sahífih-yi-Jaʿfariyyih: The Báb wrote this long essay to an unknown person in 1845. It explains many of his basic teachings, especially related to some Shaykhi beliefs.

- Tafsír-i-Súrih-i-Kawthar ("Tafsir on the Surah al-Kawthar"): The Báb wrote this commentary for Yahyá Dárábí Vahíd while in Shiraz. Although the surah is very short, the commentary is over two hundred pages long. It was widely shared.

Writings from Isfahan (1846–1847)

- Nubuvvih khásish: This 50-page work was revealed in two hours in response to a question from Governor Manouchehr Khan Gorji. It discusses the special prophethood of Muhammad.

- Tafsír-i-Súrih-i-va'l-ʿasr (Commentary on the Surah al-ʿAṣr): This was one of two important works the Báb wrote in Isfahan. He wrote it quickly and publicly, surprising those present.

Writings from Maku (1847–1848)

The Báb was sent to a fortress at Maku, Iran, near the Turkish border. Here, he wrote some of his most important works.

- Persian Bayán: This is considered the Báb's most important work. It summarizes his teachings and was written in Maku. It has nine chapters, usually divided into nineteen sections. The Báb said that "He Whom God shall make manifest" would complete this work. Baháʼís believe Baháʼu'lláh's Kitáb-i-Íqán is its completion.

- Arabic Bayán: This is a shorter and less important version of the Bayán. It has eleven chapters, each with nineteen sections. It briefly summarizes the Báb's teachings and laws.

- Dalá'il-i-Sab'ih ("Seven Proofs"): There are two works with this name, one in Persian and one in Arabic. Both were written in Maku. The Persian version is considered very important for explaining his ideas.

Writings from C͟hihríq (1848–1850)

The Báb spent two years in Chehriq, except for his brief trial visit to Tabriz. The works he wrote here were more spiritual or mystical and less organized by topic.

- Kitabu'l-Asmáʼ ("The Book of Names"): This is a very long book about the names of God. It was written during the Báb's last days in Chehriq, before his execution.

- Kitáb-i-panj sha'n ("Book of Five Grades"): This is one of the Báb's last works, written in March and April 1850. It has 85 sections arranged in 17 groups, each named after a different name of God. Each group has five different types of sections: verses, prayers, sermons, commentaries, and Persian pieces.

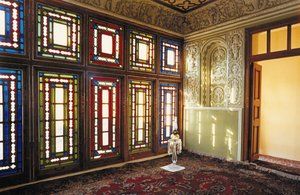

Images for kids

-

The room where the Declaration of the Báb took place on the evening of 22 May 1844, in his house in Shiraz.

-

The barrack square in Tabriz, where the Báb was executed

See also

In Spanish: Báb para niños

In Spanish: Báb para niños

- List of Mahdi claimants

- List of founders of religious traditions

- Twin Holy Birthdays

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |