The Black Boys rebellion facts for kids

The Black Boys Rebellion, also known as Smith's Rebellion or the Allegheny Uprising, was a conflict between colonists in Pennsylvania and the British Army. It lasted for nine months, from March to November 1765. The trouble began when a group of colonists, led by James Smith, found a wagon train carrying goods meant for Native Americans. Some of these goods were considered "warlike" and illegal by the colony's rules.

The colonists stopped the wagons at Sideling Hill and destroyed the goods. This led to many clashes, including more destruction, small battles, arrests, and even a siege. One colonist, James Brown, was wounded. Some people believe this was the first injury in what would become the American Revolutionary War.

Contents

- Life on the Pennsylvania Frontier

- James Smith and the Black Boys

- George Croghan's Trade Plans

- Baynton, Wharton, and Morgan

- Incident at Pawling's Tavern, March 5, 1765

- Goods Destroyed at Sideling Hill, March 6, 1765

- First Clash with British Soldiers

- The Black Boys' Inspection System

- Shootout at Widow Barr's

- Arrest Warrant for Sgt. Leonard McGlashan

- Song About the Black Boys

Life on the Pennsylvania Frontier

By 1763, France had lost its lands in North America to Britain and its colonies. This meant Native American groups who had been allies with the French were losing their power. To get it back, Chief Pontiac united different Native American nations. Their goal was to push British settlers as far east as possible.

This conflict, called Pontiac's War, reached western Pennsylvania. The Allegheny Mountains became the front line. In the valleys of these mountains was the Conococheague settlement. This area stretched from western Maryland into south-central Pennsylvania, along the Conococheague Creek. Many Scots-Irish and German immigrants lived here. The government in Philadelphia offered this land cheaply. However, these settlers also acted as a barrier between Native American lands and wealthier European towns. When Pontiac's warriors attacked homes and killed people, great fear spread through the region.

In 1764, it seemed like the frontier might become peaceful again. Pontiac's forces had been defeated at the Battle of Bushy Run. Colonel Henry Bouquet was talking with the Ohio Native Americans. It looked like Europeans captured during the French and Indian War would return home. To prevent future fights, Britain created new rules called the Royal Proclamation of 1763.

These rules said that Native Americans could not receive "warlike" trade items like guns, knives, tomahawks, gunpowder, or alcohol. Europeans were also forbidden from settling beyond a special line. This Proclamation Line ran through the middle of present-day Pennsylvania. It marked the official edge of western expansion.

However, in June 1764, fighting started again. On June 26, four Lenape warriors attacked a schoolhouse near Greencastle, Pennsylvania. They killed ten children and their teacher, Enoch Brown. Before this, they had also killed a pregnant woman, Susan King Cunningham, near Fort Loudoun. These events deeply shocked the German and Scots-Irish communities.

The Conococheague settlement, in what is now Franklin County, Pennsylvania, was right next to the Proclamation Line. Even though the rules said no one could move west, that was the only direction for new settlements. The next step for expansion was the Ohio country. Businessmen and land investors understood this very well.

James Smith and the Black Boys

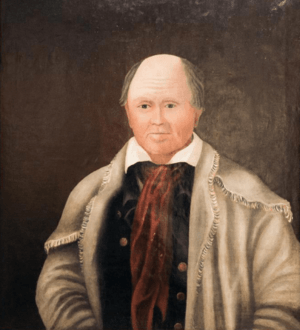

Frontier settlers wanted protection from Native American raids. They raised money to create a group of rangers to defend their homes. The leader of these rangers was James Smith, a 28-year-old Scots-Irish immigrant.

When he was a teenager in 1755, James Smith joined a crew building a road. This was during the French and Indian War. One day, Native American scouts captured him. He was taken to Fort Duquesne and forced to run the gauntlet (a painful ritual). He survived and was adopted into an Ohio tribe. He lived as a Native American for five years before escaping back to Conococheague in 1760.

Because he knew so much about Native American ways of living and fighting, Smith was the perfect choice to lead the defense of Conococheague in 1763. He chose two other men, who had also been captured, to help him lead. About 30 to 35 German and Scots-Irish men volunteered. Smith trained them in Native American fighting styles. Each man brought his own gun. Smith described how they dressed:

- They wore breech-clout, leggings, and moccasins.

- They wore green shrouds, like Native Americans or Scottish Highlanders.

- Instead of hats, they wore red handkerchiefs.

- They painted their faces red and black, like Native American warriors.

Once trained and equipped, Smith's rangers went out on Native American trails to find the enemy. They were gone for ten months. During this time, the Conococheague settlement was mostly safe from Pontiac's Rebellion, even as other areas were attacked.

The Black Boys Name

James Smith and his men called themselves the "Loyal Volunteers" or "Sideling Hill Volunteers." The name "Black Boys" was first used by a British soldier, Sergeant Leonard McGlashan, in August 1765. He wrote: "we were fired upon warmly for some time by the Black Boys..."

The name might have come from the fact that Smith's men painted their faces. Smith himself mentioned painting faces red and black to look like Native American warriors. The rebels were seen with "black'd" faces in March and May 1765 to hide their identities. However, they soon stopped this practice. Even a small smudge of black behind the ears was enough to get someone arrested.

George Croghan's Trade Plans

A law in Pennsylvania said that trading "warlike" items like guns, knives, gunpowder, and alcohol to Native Americans was forbidden. George Croghan, who worked as a deputy Indian agent, was also not allowed to trade goods for profit or receive land from Native Americans. But he, his business partners, and the merchants in Philadelphia who supplied the goods ignored these rules.

Croghan, known as "Big Business" by Native Americans, wanted to be ready when trade with Native Americans opened up again. He planned to set up his business west of the Proclamation Line before other traders. He hoped to become very rich by buying and selling land in Ohio. The problem was how to get around the rules against trading warlike goods.

British officials, led by Colonel Henry Bouquet, needed to make peace with the Native Americans in the Ohio Country. They asked Croghan to transport British trade goods deep into that area. Croghan saw this as his chance. He bought even more goods for his own profit.

Baynton, Wharton, and Morgan

Without the knowledge of General Gage, the top army commander, George Croghan secretly contacted a Philadelphia company called Baynton, Wharton, & Morgan (BW&M) in late 1764. BW&M received goods from Britain, stored them, and sold them to other businesses. These businesses then sold or traded the goods to people on the frontier.

Croghan planned to transport goods worth a huge amount of money (between £20,000 and £30,000 sterling) from Philadelphia to Fort Pitt. There, he would open trade with the Ohio Native Americans. Croghan and his partners thought about the risks. He likely believed there would be no inspections in February 1765. So, he prepared the trade goods and loaded them onto wagons heading west.

Incident at Pawling's Tavern, March 5, 1765

On March 5, 1765, a wagon train full of goods arrived at Pawling’s Tavern in Greencastle, Pennsylvania. Eighty-one horses with pack saddles and their drivers were waiting to take the goods further. Pack horses were used because the Allegheny Mountains were very rough. Each horse could carry about 200 pounds. This "train" of 81 horses was four times larger than usual and carried about eight tons of goods.

While the goods were being transferred, one package fell. An onlooker saw what was inside and thought they looked like scalping knives. News quickly spread from Pawling’s Tavern to Greencastle that Croghan’s train was carrying illegal "warlike" goods. The recent horror of the Enoch Brown Schoolhouse attack was still fresh in people's minds.

Concerned citizens immediately asked the drivers to have their goods inspected at Fort Loudoun. The drivers ignored these requests. When the train reached Justice William Smith’s House in Mercersburg, 50 to 100 armed citizens confronted them. These citizens asked the drivers to store the goods at Fort Loudoun until a peace agreement with the Native Americans was confirmed and the Governor allowed trade. Again, the drivers refused and continued to McConnell’s Tavern.

Goods Destroyed at Sideling Hill, March 6, 1765

On March 6, 1765, worried citizens asked James Smith for help. Smith gathered his former rangers, the Black Boys, and went to stop the pack train. Around 1 o'clock that day, Smith and his men met the train at Sideling Hill, west of the Great Cove. Smith asked the drivers to turn back and get inspected at Fort Loudoun, which was the closest government authority. The drivers refused.

Smith and his men then attacked the pack train. They killed or wounded several horses and burned most of the trade goods. According to William Smith, 6 horses were killed and 60 loads of goods were burned. The drivers fled towards Fort Loudoun.

First Clash with British Soldiers

At the fort, the pack horse drivers told the commanding officer, Lieutenant Charles Grant of the 42nd Regiment of Foot, that "highwaymen" had destroyed the King's goods. They did not admit that the goods were illegal. The trader in charge had bribed Lt. Grant. So, Grant sent a patrol to the attack site. The patrol was ordered to bring back any goods that were not destroyed and to arrest anyone suspected of being involved.

Sergeant Leonard McGlashan and twelve soldiers arrived at Sideling Hill. They found a pile of burned goods. McGlashan reported seeing men with new blankets, which he believed were part of the stolen goods. His men chased and captured two prisoners.

Fifty armed citizens then confronted the soldiers. The soldiers took prisoners and weapons. Within two days, James Smith and 200-300 armed citizens surrounded the fort. On March 11, 1765, they forced Lieutenant Grant to release the prisoners. Grant refused to return the weapons, and this marked the beginning of the nine-month rebellion.

The Black Boys' Inspection System

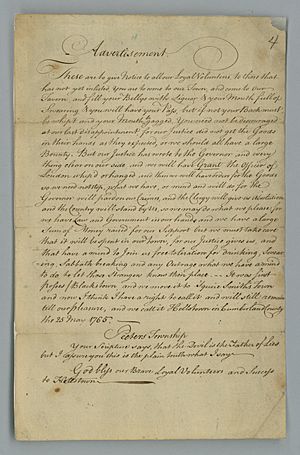

To control trade, the citizens of Conococheague announced that they would inspect all goods moving west in Pennsylvania. James Smith and Justice William Smith created a system to monitor trade until the issues with the British government were settled. Smith’s men would stop travelers and search for illegal goods without official permission from the Crown. Once a traveler was cleared, they would receive a letter of safe passage signed by either Justice Smith or James Smith.

An example of such a letter, found in the Pennsylvania State Archives, allowed a man named Thos. McCammis to pass to Fort Bedford with various goods, but specifically stated that it did not cover "Warlike Stores." It also noted that the "Sidling Hill Volunteers" had already inspected the goods and expected no trouble.

Shootout at Widow Barr's

On the morning of May 5, 1765, a messenger arrived at a tavern near Justice Smith’s home. He brought news of illegal goods moving north of Fort Loudoun. About twenty of Smith’s men quickly went to stop this pack train. They found it near Rouland Harris’s home. This train was carrying goods meant for the soldiers at Fort Pitt, ordered and paid for by Brigadier General Henry Bouquet and the Crown.

Arguments broke out between the two groups, and some horses were killed. The pack drivers fled to Fort Loudoun.

Later that evening, Lieutenant Grant heard from the panicked drivers. He ordered Sergeant McGlashan and twelve soldiers to inspect the site and arrest anyone suspicious. McGlashan found the goods burning at Harris’s place, but no one suspicious. He asked Rouland Harris to guide him to the Black Boys.

McGlashan found them about a mile north of the fort, at a house called “Widow Barr’s.” McGlashan reported what happened next:

- They were fired upon.

- McGlashan's group returned fire and took cover in Widow Barr's house.

- The Black Boys, estimated to be 70 to 80 strong, fired at them for some time.

- Before entering the house, they captured one man who had a gun and appeared to have tried to wipe black paint off his face.

- They released this prisoner after a local person warned them that they would not get back to the fort otherwise.

- McGlashan and his men then retreated back to Fort Loudoun.

Amazingly, no one was killed in the shootout, though James Brown, one of the Black Boys, was shot and wounded in the thigh. If anyone had died, the conflict likely would have gotten much worse. After the fight, Justice Smith and James Smith demanded to inspect the goods at the fort. Lieutenant Grant refused, saying they were official army goods for Fort Pitt. The Black Boys also wanted their nine firearms back, which Grant had held since March.

Arrest Warrant for Sgt. Leonard McGlashan

Soon after the shootout at Widow Barr's, the Black Boys met again at Justice William Smith's home. James Brown, who was recovering from his gunshot wound, was there. Justice Smith used his power as a magistrate (a local judge) to take legal action against the British government. He issued an arrest warrant for Sergeant Leonard McGlashan.

The warrant stated that James Brown had sworn an oath that McGlashan had shot him in the thigh. It ordered the constable to arrest McGlashan and bring him before Justice Smith or another judge to answer the complaint.

Song About the Black Boys

This song was written by George Campbell, an Irish gentleman, around 1765. It was meant to be sung to the tune of “The Black Joke.”

Ye patriot souls who love to sing, What serves your country and your king, In wealth, peace, any royal estates, Attention give whilst I rehearse, A modern fact, in jingling verse, How party interest strove what it cou’d, To profit itself by public blood, But, justly met its merited fate.

Let all those Indian traders claim, Their just reward, inglorious fame, For vile base and treacherous ends. To Pollins, in the spring they sent, Much warlike stores, with an intent To carry them to our barbarous foes, Expecting that no-body dare oppose, A present to their Indian friends.

Astonish’d at the wild design, Frontier inhabitants combin’d With brave souls, to stop their career, Although some men apostatiz’d, The bold frontiers they bravely stood, To act for their King and their country’s good, In joint league, and strangers to fear.

On March the fifth, in sixty-five, Their Indian presents did arrive, In long pomp and cavalcade, Near Sidelong Hill, where in disguise, Some patriots did their train surprise, And quick as lightning tumbled their loads, And kindled them bonfires in the woods, And mostly burnt their whole brigade.

At Loudon, when they heard the news, They scarcely knew which way to choose, For blind rage and discontent; At length some soldiers they sent out, With guides for to conduct the route, And seized some men that were trav’ling there, And hurried them into Loudon where They laid them fast with one consent.

But men of resolution thought, Too much to see their neighbors caught, For no crime but false surmise; Forthwith they join’d a warlike band, And march’d to Loudon out of hand, And kept the jailors pris’ners there, Until our friends enlarged were, Without fraud or any disguise.

Let mankind censure or commend, This rash performance in the end, Then both sides will find their account. ‘Tis true no law can justify, To burn our neighbors property, But when this property is design’d To serve the enemies of mankind, It’s high treason in the amount.

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |