The O'Rahilly facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Michael Joseph O'Rahilly

|

|

|---|---|

| Mícheál Seosamh Ó Rathaille | |

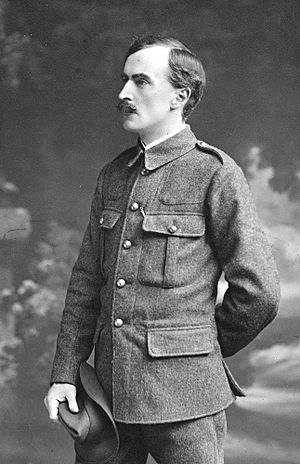

Michael Joseph O'Rahilly (The O'Rahilly) c. 1913-1916

|

|

| Born | 22 April 1875 Ballylongford, County Kerry, Ireland

|

| Died | 29 April 1916 (aged 41) Dublin, Ireland

|

| Resting place | Glasnevin Cemetery |

| Nationality | Irish – British subject |

| Other names | The O'Rahilly, Ua Rathghaille |

| Education | Clongowes Wood College |

| Organization | Irish Volunteers Gaelic League |

| Spouse(s) | Nancy O'Rahilly (m. 1899) |

| Children |

|

| Parent(s) | Ellen Mangan Richard Rahilly |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | Irish Volunteers |

| Years of service | 1913–1916 |

| Rank | Director of Arms |

| Battles/wars | Easter Rising |

Michael Joseph O'Rahilly (also known as The O'Rahilly) was an important Irish leader. He was born on April 22, 1875, and died on April 29, 1916. He helped start the Irish Volunteers in 1913. This group worked for Ireland's independence. He was in charge of getting weapons for them.

Even though he didn't agree with the plan, he took part in the Easter Rising in Dublin. He was killed during the fighting while trying to escape from the Dublin GPO.

Contents

Early Life and Work

Michael O'Rahilly was born in Ballylongford, County Kerry, Ireland. His parents were Richard and Ellen Rahilly. He went to school at Clongowes Wood College. His two sisters, Nell and Anno, were also active in the fight for Irish freedom.

As an adult, he believed Ireland should be a republic, meaning it should be a country governed by its people, not a king or queen. He also loved the Irish language. He joined the Gaelic League, a group that worked to keep the Irish language and culture alive. He traveled a lot, living in the United States and Europe for about ten years before settling in Dublin.

He married Nancy Brown in New York on April 15, 1899. They had six sons together.

O'Rahilly was one of the first members of the Irish Volunteers in 1913. This group aimed to get independence for Ireland. He was the Director of Arms, meaning he was in charge of getting weapons. He personally led the first big delivery of weapons for the Volunteers. This was when 900 rifles were brought ashore at Howth gun-running on July 26, 1914.

O'Rahilly was a rich man. He used a lot of his own money to support the cause of Irish independence.

The Irish Volunteers and the Rising

O'Rahilly was not part of the secret group that planned the Easter Rising. He was also not a member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), which was a secret society. However, he was one of the main people who trained the Irish Volunteers for battle.

The people planning the Rising tried hard to keep their plans secret from Volunteer leaders who didn't want a fight to start without good reason. These leaders included Eoin MacNeill and O'Rahilly. When another leader, Bulmer Hobson, found out about the plan, the secret planners held him against his will.

When O'Rahilly learned about this, he went to Patrick Pearse's school on Good Friday. He walked into Pearse's office, holding his gun, and said, "Whoever kidnaps me will have to be a quicker shot!" Pearse calmed him down. He told O'Rahilly that Hobson was safe and would be released after the Rising began.

O'Rahilly then followed orders from MacNeill. He spent the night driving around the country. He told Volunteer leaders in Cork, Kerry, Tipperary, and Limerick not to gather their forces for planned training on Sunday.

The Easter Rising

When O'Rahilly got home, he found out that the Rising was going to start in Dublin the very next day, Easter Monday, April 24, 1916. Even though he had tried to stop it (because he thought it would fail), he went to Liberty Hall to join the other leaders. These included Pearse, James Connolly, Thomas MacDonagh, and Countess Markievicz.

He arrived in his car and said a famous line: "Well, I've helped to wind up the clock -- I might as well hear it strike!" Another famous quote from him was to Markievicz: "It is madness, but it is glorious madness." His car was used to get supplies during the fighting. Later, it was used as a barrier on Prince's Street, where it was burned.

He fought with the group defending the GPO during Easter Week. One of the first British prisoners taken was Second Lieutenant AD Chalmers. He was tied up and put in a phone box by Michael Collins. Chalmers later remembered O'Rahilly being kind to him. He said O'Rahilly ordered: "I want this officer to watch the safe to see that nothing is touched. You will see that no harm comes to him."

On Friday, April 28, the GPO was on fire. O'Rahilly offered to lead a group of men to a factory on Great Britain Street (now Parnell Street). A British machine gun at the corner of Great Britain and Moore streets shot him and several others. O'Rahilly fell into a doorway on Moore Street, badly hurt and bleeding. He heard the British soldiers pointing out his position. He then made a run across the road to find shelter in Sackville Lane (now O'Rahilly Parade). He was shot many times from his shoulder to his hip by the machine gun.

According to a witness, O'Rahilly was still alive 19 hours after being shot, even after the Rising had ended on Saturday afternoon. He was left in the street and not allowed to be taken to a hospital.

Memorial

O'Rahilly wrote a final message to his wife, Nancy, on the back of a letter from his son. This message is carved into his memorial sculpture in Dublin. It says:

‘Written after I was shot. Darling Nancy I was shot leading a rush up Moore Street and took refuge in a doorway. While I was there I heard the men pointing out where I was and made a bolt for the laneway I am in now. I got more [than] one bullet I think. Tons and tons of love dearie to you and the boys and to Nell and Anna. It was a good fight anyhow. Please deliver this to Nannie O' Rahilly, 40 Herbert Park, Dublin. Goodbye Darling.’

The O'Rahilly House

O'Rahilly's home from 1910 to 1916 was at 40 Herbert Park. This house was sadly torn down in September 2020. Many people wanted to save it because of its history and connection to O'Rahilly.

Why "The O'Rahilly"?

In old Irish tradition, important clan leaders were sometimes called by their clan name with "the" in front, like "Robert the Bruce." O'Rahilly decided to call himself "The O'Rahilly."

In 1938, the famous poet William Butler Yeats wrote a poem called "The O'Rahilly." The poem supports O'Rahilly's choice of name, saying he earned it himself.

See also

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |