The Trafalgar Way facts for kids

The Trafalgar Way is the special route used long ago to carry important news. In 1805, after the famous Battle of Trafalgar, messengers raced along this path. They brought the exciting news of Lord Nelson's big victory and sad news of his death. The journey went from Falmouth all the way to the Admiralty (the navy's headquarters) in London.

The first messenger was Lieutenant John Richards Lapenotière. He was from a ship called HMS Pickle. He arrived in Falmouth on November 4, 1805, after a tough trip through bad weather. Then, he quickly rode to London with the crucial messages. These messages told everyone about the Battle of Trafalgar, which happened on October 21, 1805.

After Lord Nelson died in the battle, his second-in-command, Vice Admiral Cuthbert Collingwood, took charge. Collingwood's ship, the Royal Sovereign, was badly damaged. So, he moved to a ship called HMS Euryalus to keep leading the fleet. Soon after the battle, a big storm hit for several days. Collingwood had to make sure all the ships, both British and captured, were safe. He also needed to tell the Admiralty in London what had happened as fast as possible.

Contents

First News of the Battle

The First Message

Collingwood trusted Lieutenant Lapenotière to deliver the first reports of the battle. But the storm made it hard to send him right away. On Saturday, October 26, the Pickle finally set off. Lapenotière carried Collingwood's first message, written on October 22. It gave the first report of the battle. He also had a second message, written on October 24, which described how the storm affected the ships.

The Pickle reached Falmouth on Monday, November 4. Lapenotière then traveled by land to London. He rode very fast in a special carriage called a post chaise with four horses. Parts of Collingwood's messages were printed in The London Gazette on November 6. They also appeared in most newspapers.

The first report said: "I fear the numbers that have fallen will be found very great... but it having blown a gale of wind ever since the action, I have not yet had it in my power to collect any reports from the ships." This news made many people worried, especially the families of the 18,465 men who fought with Nelson. They were anxious to see the lists of those who were hurt or killed, often called the "butcher’s bill."

Lapenotière's journey was about 271 miles long. It took him 38 hours and cost £46. He stopped 21 times to change horses on the way from Falmouth to London. His "account of expenses" was kept safe by the Admiralty. It showed his route, where he changed horses, and how much it cost. The route was the main coaching road from Falmouth to London in 1805. Each part of the journey was about 10 to 15 miles. He traveled at a speed of just over 7 miles per hour.

The Race to London

Nelson had told Commander John Sykes of the 18-gun sloop HMS Nautilus to patrol near Cape St. Vincent in Portugal. On October 28, Sykes met Pickle as she sailed home. After hearing Lapenotière's news, Sykes decided to go with Pickle to keep her safe. But they lost sight of each other in the very bad weather.

When Nautilus arrived in Plymouth late on November 4, Sykes reported to Admiral William Young. The Admiral worried that Pickle might be lost. So, as a safety measure, he told Sykes to go to the Admiralty. Sykes was to report the few details he had learned about the battle from Lapenotière at sea.

As Sykes reached Exeter, neither he nor Lapenotière knew they were only a few miles apart on the same road. They were in an unplanned race to London! By the time they reached Dorchester, reports said the two officers were only an hour apart. Sykes arrived at the Admiralty at 2 a.m. on Wednesday, November 6. He was about an hour behind Lapenotière.

More Important Messages

The Second Message

By October 28, Collingwood had moved his flag to Euryalus. He was then able to send a second message with more information from some of the ships. Lieutenant Robert Benjamin Young, who commanded the small ship HMS Entreprenante, took this message to Faro in Portugal. There, it was given to the British consul, who sent it to the British Embassy in Lisbon.

From Lisbon, the message sailed on November 4 aboard the regular mail ship Lord Walsingham. This ship reached Falmouth on November 13. A special carriage then carried the mail along the same route Lapenotière had taken. It reached the Admiralty in London on Friday, November 15. The lists of casualties (those hurt or killed) appeared in The Times newspaper on Monday, November 18. This finally ended eleven days of worry for the families of men from many ships, including Royal Sovereign and Mars.

The Third Message

By November 4, the damaged British ships were getting organized again. Collingwood had moved his flag from Euryalus to HMS Queen. This was a larger ship that had rejoined Collingwood after the battle. Good progress was also being made in sending the Spanish prisoners back to Spain.

Collingwood was now able to send the Euryalus to England with his third message. She sailed from off Cape Trafalgar on November 7. On board was the captured French Commander in Chief, Admiral Pierre de Villeneuve. On Sunday, November 24, news came from Falmouth: "The hon. Capt. Blackwood landed here this evening, from his majesty's ship Euryalus... and came up in his 8-oared cutter; he went off express for London immediately."

Blackwood followed Lapenotière's route. He reached London late on November 26. The Times on Thursday, November 28, published Collingwood's report. It described the condition and location of the defeated French and Spanish ships, along with a list of captured ships. This message also had more casualty lists, including the first details from ships like Victory and Britannia. The report mentioned that four French ships had "hauled to the Southward and escaped." Collingwood did not know where they were when he wrote his third message.

Other Important Messages

The Admiralty, however, was not worried. They had already received good news about the escaped French ships from another messenger. On Saturday, November 9, the ship Aeolus sailed into Plymouth. She brought news that the escaped ships had been captured by Captain Sir Richard Strachan near Cape Ortegal on Monday, November 4.

The captain of Aeolus, Lord Fitzroy, "set off with dispatches at 10 A.M. for the Admiralty, (the horses decorated with laurels) in a post-chaise and four." The next day, Captain Baker of the Phoenix arrived in Plymouth. He took another carriage to London with more details about the Ortegal battle, including the British casualty lists. The information these officers carried was published in London on November 11 and 12.

Even though Lord Fitzroy and Captain Baker started from Plymouth, they joined The Trafalgar Way at Exeter and followed it to London.

Collingwood's Final Message

The last news from Trafalgar included the casualty list from the ship Tonnant. This was published in London on December 4. Collingwood did not receive this information until November 9. This was when Queen anchored near Cape Spartel after Euryalus had left. The message with this report was sent to Lisbon. From there, it traveled by the regular mail ship Townshend, arriving at Falmouth on Friday, November 29. The mail she carried was taken along the same well-known route to the Admiralty.

2005 Commemoration

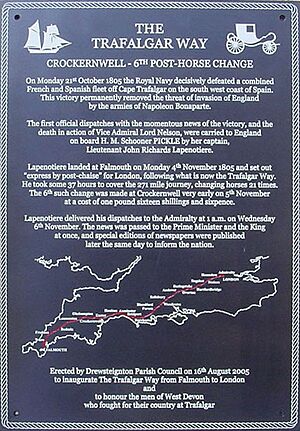

Lieutenant Lapenotière's 37-hour journey and the trips of the other messengers were remembered in 2005. This was done by starting The Trafalgar Way and holding the New Trafalgar Dispatch celebrations. Her Royal Highness the Princess Royal unveiled a special plaque in Falmouth on August 4, 2005. This began a series of events along the route.

Many special plaques now mark the route. They share details of Lapenotière's journey and honor local people who fought with Nelson at Trafalgar. You can see these plaques in many towns, including Falmouth, Truro, Exeter, Salisbury, and London.

The Ordnance Survey (a mapping agency) created a special map of the route to celebrate. It included descriptions and a historical timeline. In 2017, the group that looks after The Trafalgar Way, The 1805 Club, received money to help promote the route and its history again.

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |