Three-spined stickleback facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Three-spined stickleback |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Genus: |

Gasterosteus

|

| Species: |

aculeatus

|

| Synonyms | |

|

|

The three-spined stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus) is a small fish found in many waters north of 30°N latitude. This includes inland lakes, rivers, and coastal areas. Scientists love to study this fish for many reasons.

It comes in many different shapes and sizes. This makes it perfect for learning about evolution and how animal groups change over time. Many sticklebacks are anadromous. This means they live in salty ocean water but travel to fresh or slightly salty water to lay their eggs. They can handle big changes in how salty the water is.

Sticklebacks also have interesting breeding habits. The male builds a nest and takes care of the eggs and young fish. Outside of the breeding season, they often live in groups called shoals. This makes them great for studying fish behavior. Scientists also study how they avoid predators, how they interact with parasites, and how their bodies work. It's easy to find them in nature and keep them in aquariums, which helps with all these studies.

Contents

- What Does a Stickleback Look Like?

- Where Do Sticklebacks Live?

- How Sticklebacks Change and Adapt

- What Do Sticklebacks Eat?

- Life Cycle of the Stickleback

- Reproduction and Nest Building

- Working Together: Cooperative Behavior

- How Sticklebacks See and Sense

- Parasites

- Stickleback Genetics

- See also

- Images for kids

What Does a Stickleback Look Like?

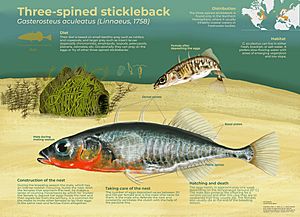

This fish can grow up to 8 cm (3.1 in) long. However, most adult sticklebacks are about 3–4 centimetres (1.2–1.6 in) long. Their bodies are flat from side to side. The part of the body before the tail is thin. The tail fin has 12 rays, which are like the bones that support the fin.

The dorsal fin (on the back) has 10–14 rays. In front of this fin are three sharp spines. These spines give the fish its name! Sometimes, a stickleback might have only two or four spines. The third spine, closest to the dorsal fin, is shorter than the other two. Each spine is connected to the body by a thin membrane.

The anal fin (on the belly, near the tail) has 8 to 11 rays and one short spine in front of it. The pelvic fins (on the belly, near the head) have only one spine and one ray. All these spines can stand straight up. This makes the fish very hard for predators to swallow. The pectoral fins (on the sides, behind the head) are large and have 10 rays.

Sticklebacks do not have scales. Instead, their bodies are covered by bony plates on their back, sides, and belly. There is only one plate on the belly. The number of plates on their sides changes a lot depending on where they live. Fish living in the ocean usually have more plates. Some freshwater sticklebacks might not have any side plates at all.

Their color on top is usually a dull olive green or silvery green. Sometimes, they have brown spots. Their sides and belly are silvery. During the breeding season, male sticklebacks change color. Their eyes turn blue, and their lower head, throat, and front belly become bright red. Female sticklebacks might get a slightly pink throat and belly. In some places, breeding males can even be all black or all white.

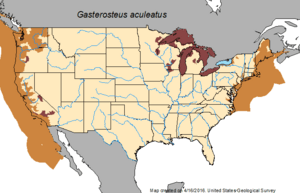

Where Do Sticklebacks Live?

The three-spined stickleback lives only in the Northern Hemisphere. You can usually find them in coastal ocean waters or in freshwater bodies. They can live in fresh, slightly salty (brackish), or fully salty water. They like water that flows slowly and has lots of plants. You can find them in ditches, ponds, lakes, quiet rivers, sheltered bays, marshes, and harbors.

In North America, they live along the East Coast from Chesapeake Bay up to Baffin Island. On the West Coast, they are found from southern California up to Alaska and the Aleutian Islands. In Europe, they live between 35 and 70°N latitude. In Asia, they are found from Japan and Korea to the Bering Straits.

They are found almost all around the North Pole. However, they are not found along the north coast of Siberia, the north coast of Alaska, or the Arctic islands of Canada.

How Sticklebacks Change and Adapt

Scientists recognize three main types, or subspecies, of three-spined sticklebacks:

- G. a. aculeatus: This is the most common type. It is found in most places where sticklebacks live. In Britain, it's sometimes called the "tiddler."

- G. a. williamsoni: This type is called the "unarmored threespine stickleback." It is found mostly in southern California, but has also been seen in British Columbia and Mexico.

- G. a. santaeannae: This type is called the "Santa Ana stickleback." It is also found only in North America.

These types show how much sticklebacks can change their looks. They generally fall into two groups: those that live in the ocean (anadromous) and those that live in freshwater.

Ocean and Freshwater Forms

The ocean-dwelling sticklebacks spend most of their lives eating tiny plants and animals (plankton) and small fish in the sea. They return to freshwater to breed. These adult fish are usually 6 to 10 cm long. They have 30 to 40 bony plates along their sides. They also have long spines on their back and belly. Ocean sticklebacks look very similar all around the Northern Hemisphere.

Three-spined sticklebacks also live in freshwater lakes and streams. These populations likely started when ocean sticklebacks began to live their whole lives in freshwater. Over time, they evolved to stay there year-round. Freshwater sticklebacks look very different from each other. Many scientists think that almost every lake in the Northern Hemisphere could have its own unique type of stickleback!

One big difference is how much body armor they have. Most freshwater fish have between zero and 12 side plates. They also have shorter spines. However, there are also big differences between fish in different lakes. For example, fish in deep lakes often eat plankton near the surface. They usually have large eyes, slim bodies, and jaws that point up. These are sometimes called the "limnetic" form. Fish from shallow lakes mostly eat food from the lake bottom. They are often long and heavy, with smaller eyes and jaws that are more horizontal. These are called the "benthic" form.

Rapid Evolution in Lakes

In some lakes, you can find both the limnetic and benthic types. These two types do not breed with each other. When animals don't interbreed, scientists often consider them different species. This is a great example of how adapting to different environments (like eating at the surface or on the lake bottom) can create new species. This process is called ecological speciation.

Sadly, some of these unique fish pairs have been lost. For example, a pair in Hadley Lake was destroyed by a new type of fish introduced in the 1980s. Another pair in Enos Lake started interbreeding and are no longer distinct species. Two remaining pairs in Paxton Lake and Priest Lake on Texada Island are now listed as endangered.

Scientists are also studying stickleback pairs in Alaska. These lakes were once part of the ocean. In one lake, Loberg Lake, the freshwater sticklebacks were removed in 1982. Ocean sticklebacks then came into the lake. In just 12 years, from 1990, the ocean form became less common. A type with fewer plates increased to 75% of the population. This shows how quickly sticklebacks can evolve to fit a new environment. This rapid change is thought to be due to genetic differences that help them survive better in freshwater.

Even though sticklebacks are common worldwide, many freshwater populations have a special evolutionary history. This means they might need extra protection.

What Do Sticklebacks Eat?

Three-spined sticklebacks eat different things depending on their type and age. They can eat things from the bottom of the water, like insect larvae. They also eat tiny creatures floating in the water (plankton) in lakes or the ocean. Sometimes, they eat insects that fall onto the water's surface. They can also eat their own eggs and young fish.

Life Cycle of the Stickleback

Many stickleback populations take two years to grow up. They usually breed only once before they die. Some can take up to three years to become adults. However, some freshwater populations and those in very cold places can become adults in just one year.

Reproduction and Nest Building

From late April, male and female sticklebacks move from deeper waters to shallow areas. Each male then finds a territory and builds a nest on the bottom.

First, he digs a small pit. Then, he fills it with plants, sand, and other bits he finds. He glues these materials together using a sticky substance called spiggin. This substance comes from his kidneys. The nest is usually round. He then swims forcefully through the nest to create a tunnel. Building a nest usually takes 5–6 hours, but it can take several days.

After the nest is ready, the male tries to attract females that are full of eggs. He does a special "zigzag dance." He swims short distances left and right, then swims back to the nest in the same way. If a female follows him, he often pokes his head into the nest. He might even swim through the tunnel. The female then swims through the tunnel and lays 40–300 eggs. The male follows to fertilize the eggs. After this, the male chases the female away.

While the eggs are developing, the male guards the nest. He chases away other males and females that are not ready to lay eggs. However, he might court other females and let them lay eggs in the same nest.

Male Color and Mating

The famous scientist Niko Tinbergen studied the stickleback's mating behavior in detail. He showed that the bright red color on the male's throat is a "sign stimulus." This means it triggers specific behaviors. It makes other males aggressive and attracts females.

Females also use the red color to decide if a male is a good mate. The red color comes from special pigments called carotenoids that the fish get from their food. Fish cannot make these pigments themselves. So, a brighter red color shows that the male is good at finding food. Males with fewer parasites also tend to be brighter red. Many studies show that females prefer males with brighter red colors. However, in some populations, males have black throats, especially in waters stained by peat.

Caring for the Eggs

The male stickleback takes care of the developing eggs by fanning them. He positions himself at the nest entrance and swims in place. His pectoral fins create a current of water through the nest. This brings fresh, oxygen-rich water to the eggs. He does this all day and all night.

He fans more as the eggs get closer to hatching. This usually takes 7–8 days at 18–20 °C (64–68 °F). He also fans more if the water has less oxygen. As the eggs develop, the male often makes holes in the nest. This helps improve air flow during fanning, especially when the eggs need more oxygen.

Once the young fish hatch, the male tries to keep them together for a few days. If any young fish swim away, he sucks them into his mouth and spits them back into the nest. After a few days, the young fish swim off on their own. The male then either leaves the nest or fixes it up for another round of breeding.

Working Together: Cooperative Behavior

Sticklebacks show some cooperative behavior, especially when checking out predators. This is called "predator inspection." When a stickleback goes to inspect a predator, it gathers information about how dangerous the predator is. This might even scare the predator away. The risk is that the stickleback might get attacked if the predator is hungry.

Tit-for-Tat Strategy

Sticklebacks are known to use a "tit-for-tat" (TFT) strategy when inspecting predators. This means:

- They cooperate (go closer to the predator) on the first move.

- Then, they do whatever their partner did on the previous move.

This strategy allows them to cooperate, get back at a partner who doesn't cooperate, and forgive a partner who starts cooperating again. When sticklebacks were shown a fake partner that either cooperated or didn't, they acted like the tit-for-tat strategy. This shows that cooperation can happen even among animals looking out for themselves.

Sticklebacks often work in pairs. They repeatedly visit predators together. This shows they form partnerships. This behavior further supports the idea of a tit-for-tat cooperation strategy.

Sticklebacks from places with more predators tend to be more cooperative. They are more likely to cooperate if their partner cooperates. This shows that their cooperation strategy is similar to tit-for-tat.

How Partner Size Affects Behavior

The size of a stickleback's partner can also affect how it acts when facing a predator. If two sticklebacks approach a large predator like a rainbow trout, the larger stickleback usually has a higher chance of being attacked.

A stickleback is more likely to go closer to a predator if its partner is larger and also moves closer. If the partner is smaller, its behavior affects the test fish more. A larger stickleback will generally approach a predator more closely than a smaller one, whether it's alone or with a cooperative partner. If a partner doesn't cooperate, then the stickleback's ability to flee (its "condition-factor") determines how close it gets to the predator, not its size. So, how sticklebacks act depends on both their partner's size and whether the partner cooperates.

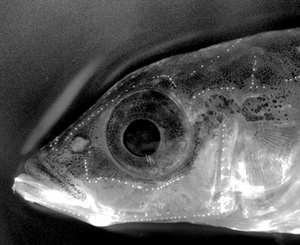

How Sticklebacks See and Sense

Sticklebacks have four types of color-sensing cells in their eyes. This means they can potentially see more colors than humans! They can even see ultraviolet light, which humans cannot see. They use these different wavelengths of light in their normal behaviors.

Parasites

The three-spined stickleback can be a host for a tapeworm called Schistocephalus solidus. This tapeworm also lives in fish-eating birds.

Stickleback Genetics

Three-spined sticklebacks have become very important for scientists studying evolution. They help us understand the genetic changes that happen when animals adapt to new environments. The entire set of genes (genome) of a female stickleback from Bear Paw Lake in Alaska has been mapped. This population is at risk because of northern pike introduced into a nearby lake.

See also

In Spanish: Espinoso para niños

In Spanish: Espinoso para niños

Images for kids