Tobacco Kiln, Oak Valley facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Tobacco Kiln |

|

|---|---|

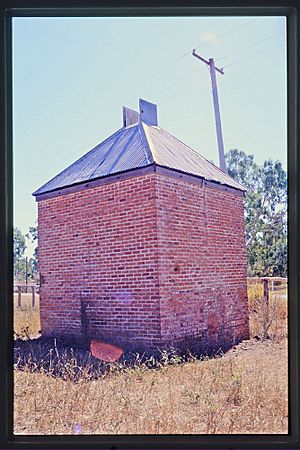

Tobacco Kiln, Oak Valley, July 2002

|

|

| Location | 12 Chisholm Trail, Oak Valley, City of Townsville, Queensland, Australia |

| Design period | 1919 - 1930s (interwar period) |

| Built | c. 1933 |

| Official name: Tobacco Kiln, Flue Curing Barn | |

| Type | state heritage (built) |

| Designated | 27 September 2002 |

| Reference no. | 602343 |

| Significant period | 1933 (fabric) 1930s (historical) |

| Significant components | kiln - tobacco drying, flue |

| Builders | Dick Moyes |

| Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 420: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). | |

The Tobacco Kiln is a special old building in Oak Valley, near Townsville, Queensland, Australia. It's a type of kiln or oven that was used to dry tobacco leaves. This kiln was built around 1933 by Dick Moyes. It's also known as a Flue Curing Barn. This historic building is so important that it was added to the Queensland Heritage Register on 27 September 2002.

Why Was This Kiln Built?

This brick tobacco kiln, which is about 4 metres (13 feet) square, stands on a small piece of land in Oak Valley. When it was built around 1933, this land was part of a much larger farm owned by Elias Emmanuel. The kiln was a key part of growing tobacco in the area.

In the early 1930s, the tobacco industry grew a lot in North Queensland. This happened because the government wanted to help people find jobs during the Great Depression. This was a time when many people around the world were out of work. Growing tobacco was a way to boost local economies.

Finding the Best Places to Grow Tobacco

The Australian and Queensland governments worked with a company called British-Australian Tobacco to find good places to grow tobacco. They tested many areas, including one near Townsville called Hervey's Range. These tests showed that North Queensland could grow bright, good-quality tobacco.

Because of these successful tests, Mareeba became a main area for tobacco farming. The government even set up an experimental farm there. Other places like Pentland and Charters Towers also started growing tobacco.

Tobacco Farming Comes to Townsville

The demand for tobacco land quickly spread. In 1931, tobacco farming started in the Major's Creek and Woodstock areas, which included Oak Valley. At its peak in 1932, there were 31 tobacco farms in this area. However, by 1940, tobacco growing had stopped there.

Why Did Tobacco Farming End in Townsville?

Several things caused the tobacco industry in Townsville to fail:

- Lack of Support: Farmers in Mareeba had help from a government experimental farm. Townsville farmers didn't get this kind of support.

- Water Problems: Tobacco plants needed just the right amount of water. Too much or too little rain during the wet season could ruin the crop.

- Diseases and Pests: Tobacco plants were easily affected by diseases and pests. Farmers often didn't know how to deal with these problems.

- Curing Challenges: Drying the tobacco leaves correctly was a very tricky process. Inexperienced farmers found this difficult.

- Government Rules: Sometimes, government rules made it harder for local farmers to sell their tobacco for a good price.

Setting up a tobacco farm was also very expensive, costing about £950 in the 1930s. This included buying land, building sheds, and getting equipment.

The Importance of Curing Barns

One of the biggest costs was building a curing barn, like the Tobacco Kiln. These barns were essential because tobacco leaves had to be dried right after they were picked. Farmers used different materials for their kilns, such as brick, corrugated iron, or even sun-dried bricks made of clay and grass.

The kiln at 12 Chisholm Trail used a modern method called "flue curing." This method used pipes, called flues, to carry heat from an outside furnace across the barn. This heated the air inside, drying the tobacco without smoke touching the leaves. This gave farmers much better control over the heat and moisture.

How Tobacco Was Cured

The goal of curing was to make the tobacco leaves a bright yellow color, like a fresh lemon. After picking, leaves were tied to sticks and hung inside the barn. The curing process had three main steps:

- Yellowing: The leaves were kept in a warm, humid place to finish ripening.

- Fixing the Color: The heat was increased, and the air was made less humid. This dried the leaf veins.

- Drying Completely: The heat was increased even more, and ventilation was reduced until the whole leaf and stem were dry.

This process needed special skills to control the heat and humidity. It was a big challenge for new farmers.

The Kiln's Age and Survival

The Tobacco Kiln was likely built around 1933. A piece of iron in the top vent has a "queen's head" symbol with the number "33" below it. This mark shows it was made by a company called Lysaght in 1933. Since the tobacco industry in Townsville started to decline after 1932, it's unlikely the kiln was built much later.

The bricks used were probably bought from a company, but there were also local brick makers. Building with brick and iron was expensive, showing how much farmers were willing to invest.

Today, this brick tobacco kiln is likely the only one in the area that still has parts of its original flues and tier poles. This means it was probably never used for other purposes, making it a rare historical reminder.

Lasting Impact of the Tobacco Industry

Even though the Townsville tobacco industry was short-lived, it had some positive effects. It led to the creation of the Townsville and District Development Association. It also helped get a new road built, which provided jobs during the Great Depression. A local tobacco grading company also offered employment. The kiln at 12 Chisholm Trail reminds us of this important time in Townsville's history.

What Does the Kiln Look Like?

The Tobacco Kiln is an almost square brick building. It sits on a small piece of land at 12 Chisholm Trail in Oak Valley. The building is about 4.12 metres (13.5 feet) long on the east and west sides, and 4.1 metres (13.4 feet) long on the north and south sides. The walls are about 4.25 metres (13.9 feet) tall.

The walls are made of single layers of clay bricks. These bricks are a bit smaller than standard bricks. The bricks are laid in a pattern called "stretcher bond," with rough mortar between them. At the top, the brick walls have a timber frame and are held together inside by steel bolts.

The Roof and Ventilator

The roof is shaped like a pyramid, but the very top is cut off to make space for a square ventilator. The roof is made of timber and covered with corrugated iron. Inside, it's lined with an insulating material, possibly fibro cement. The ventilator on top also has flat metal sheets and the same insulating material. The metal sheet on the west side of the ventilator clearly shows the "queen's head" and "33" mark.

Inside the Kiln

The outside furnace area of the kiln is no longer there, but you can still see where it was on the eastern side. There's a round opening for a flue (pipe) about 1.5 metres (5 feet) from the northern edge. The corrugated roof above this area was cut and bent, showing where the chimney used to be.

Inside, you can see another flue opening on the western wall. On the dirt floor, there are still parts of two iron flues. These were round pipes that carried heat across the barn and back again. You can also see some old timber poles along the northern wall. These were used to hang the tobacco leaves.

The original door on the western wall is missing. The opening is now closed off with timber and corrugated sheeting for safety.

Why is This Kiln a Heritage Site?

The Tobacco Kiln was added to the Queensland Heritage Register because it meets several important criteria:

Showing Queensland's History

The kiln, built around 1933, is important because it shows how Queensland's history unfolded. It's a physical reminder of an agricultural industry that started to help people during the Great Depression. Both the Queensland and Australian governments tried to find good land for growing tobacco to create jobs and boost local economies. This kiln also shows how agriculture has always been a key part of settling land in Queensland.

A Rare Piece of History

This tobacco kiln is a rare part of Townsville's history because tobacco is no longer grown in this area. It's especially rare because it still has its original flues and tier poles, meaning it was never changed for other uses.

Showing How Things Were Done

The tobacco kiln shows the main features of "flue curing," which was the most modern and scientific way to dry tobacco in the 1930s. Its design was very similar to what experts recommended in agricultural journals at the time. The large amount of money spent to build it shows either strong belief in new farming methods or a desperate effort to survive during tough economic times.

| Victor J. Glover |

| Yvonne Cagle |

| Jeanette Epps |

| Bernard A. Harris Jr. |