Tonypandy riots facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Miners Strike of 1910-11 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Great Unrest | |||

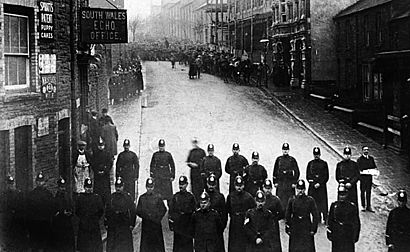

Police blockade a street during the events of 1910–1911

|

|||

| Date | September 1910 - August 1911 | ||

| Location | |||

| Caused by | Lock-out in Penygraig | ||

| Goals | Higher wages, better living conditions | ||

| Methods | Strike action Rioting |

||

| Resulted in | Negotiated end to the strike | ||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

|

|||

| Lead figures | |||

|

|||

| Number | |||

|

|||

| Casualties | |||

| Death(s) | 1 miner | ||

| Injuries | 80 police and over 500 citizens | ||

| Arrested | 13 miners | ||

The Miners Strike of 1910-11 was a big protest by coal miners and their families in South Wales. They wanted better pay and living conditions. Mine owners had kept wages very low for a long time.

The Tonypandy riots (also called the Rhondda riots) were a series of violent clashes. They happened between striking coal miners and police. These events took place in and around the Rhondda mines. The mines were owned by the Cambrian Combine. This was a group of mining companies that worked together. They controlled prices and wages in South Wales.

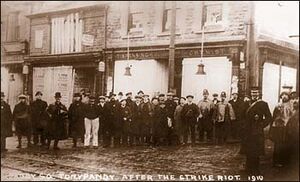

These clashes were the peak of a long argument between workers and mine owners. The name "Tonypandy riot" first referred to events on November 8, 1910. On that night, strikers broke windows of shops in Tonypandy. There was also fighting between strikers and the Glamorgan Constabulary. Police from Bristol came to help.

Winston Churchill, who was the Home Secretary at the time, decided to send the British Army to the area. This was to help the police. His decision made many people in South Wales angry. His role in these events is still debated today.

Contents

Why Did the Strike Happen?

The conflict started at the Ely Pit in Penygraig. The Naval Colliery Company opened a new coal seam there. After a short test, the owners said miners were working too slowly. The roughly 70 miners at the seam disagreed. They said the new seam was harder to work. This was because of a stone band running through it.

On September 1, 1910, the owners closed the mine. This was a lock-out. It affected all 950 workers, not just the 70 at the new seam. The Ely Pit miners then went on strike. The Cambrian Combine brought in strikebreakers from other areas. The miners responded by picketing the mine entrance.

On November 1, 12,000 miners voted to strike. These miners worked for the Cambrian Combine mines. A group was formed to find an agreement. William Abraham spoke for the miners. F. L. Davis spoke for the owners. They agreed on a wage of 2 shillings and 3 pence per ton. But the Cambrian Combine workers rejected this deal.

By November 2, authorities in South Wales were asking for military help. They worried about more trouble from the striking miners. The Glamorgan Constabulary was already busy. There was another strike in the nearby Cynon Valley. By November 6, the Chief Constable of Glamorgan had brought 200 extra police to Tonypandy.

What Happened During the Riots?

The strikers had managed to shut down all local mines. Only the Llwynypia colliery was still open. On November 6, miners learned that owners planned to use strikebreakers there. These workers would keep pumps and ventilation going. On November 7, strikers surrounded the Glamorgan Colliery. They wanted to stop workers from entering.

This led to fights with police officers inside the mine. Miners' leaders asked for calm. But a small group of strikers began throwing stones at the pump-house. Part of the wooden fence around the mine was torn down. Miners and police fought hand-to-hand. Police used batons to push strikers back towards Tonypandy Square. This happened just after midnight.

Between 1 AM and 2 AM on November 8, a protest at Tonypandy Square was broken up. Police from Cardiff used truncheons. Both sides had injuries. After this, Glamorgan's chief constable, Lionel Lindsay, asked for military help. The general manager of the Cambrian Combine supported this request.

Home Secretary Winston Churchill heard about this. He talked with the War Office. Churchill felt the local police were overreacting. He believed the government could calm things down. So, he sent Metropolitan Police officers instead. Some cavalry troops were sent to Cardiff. Churchill did not directly send cavalry to Tonypandy. But he allowed local authorities to use them if needed. Churchill's message to the strikers was: "We are holding back the soldiers for the present and sending only police."

Despite this, the local judge sent a telegram to London later that day. He again asked for military support. The Home Office approved it. Troops were sent after the fight at the Glamorgan Colliery on November 7. They arrived before the main rioting on the evening of November 8.

During the evening of November 8, shops in Tonypandy were damaged. Some items were taken. Shops were broken into in a planned way, not randomly. There was not much stealing. But some rioters wore clothes taken from shops. They paraded around in a happy mood. Many women and children were involved. They had also been outside the Glamorgan colliery.

No police were seen in the town square until the Metropolitan Police arrived. This was around 10:30 PM, almost three hours after the rioting began. By then, the disturbance was already calming down. A few shops were not touched. One was a chemist shop owned by Willie Llewellyn. People said it was spared because he was a famous Welsh international rugby player.

A small police presence might have stopped the window breaking. But police had been moved from the streets. They were protecting the homes of mine owners and managers.

At 1:20 AM on November 9, orders were sent to Colonel Currey in Cardiff. A group of the 18th Hussars was to reach Pontypridd by 8:15 AM. One group patrolled Aberaman. Another was sent to Llwynypia and patrolled all day. Returning to Pontypridd at night, the troops arrived at Porth. A disturbance was starting there. They kept order until the Metropolitan Police arrived.

No official record of injuries exists. Many miners likely did not seek treatment. They feared being arrested for their part in the riots. But nearly 80 police officers and over 500 citizens were injured. One miner, Samuel Rhys, died from head injuries. People said a policeman's baton caused them. But the jury's decision was careful. They said he died from injuries on November 8. But they were not sure how he got them. Medical evidence said the injury was from a blunt object. It could have been a police truncheon. Or it could have been one of the weapons used by strikers.

Authorities sent more help to the town. There were 400 policemen. One company of the Lancashire Fusiliers stayed at Llwynypia. And the group of the 18th Hussars was also there.

Thirteen miners from Gilfach Goch were arrested. They faced trials for their actions. Their trial lasted six days in December. During the trial, up to 10,000 men marched and protested to support them. These men were not allowed into the town. Some miners were sent to jail for two to six weeks. Others were released or fined.

Why Was Churchill Criticized?

Churchill's actions during the Tonypandy conflict caused lasting anger in South Wales. The main issue was his decision to send troops to Wales. This was unusual and seen as too much by people in Wales. But his political opponents thought he should have acted even more strongly.

The troops acted more carefully than the police. The police, led by Lionel Lindsay, were described by historian David Smith as acting "more like an army of occupation."

This event continued to affect Churchill's career. The feelings were so strong that almost 40 years later, he had to address it. In 1950, he spoke in Cardiff during an election campaign. He said: "When I was Home Secretary in 1910, I had a great horror and fear of having to become responsible for the military firing on a crowd of rioters and strikers. Also, I was always in sympathy with the miners..."

A big reason for the dislike of Churchill's use of the military was not what the troops did. It was that their presence stopped any strike action. Such action might have ended the strike early in the miners' favor. The troops also made sure that trials of rioters and strike leaders happened. These trials were successful in Pontypridd in 1911. Many locals saw the miners' defeat in 1911 as a direct result of the government stepping in without talking. For many locals, the fact that strikers were breaking the law was not important. They saw this outcome as a direct result of Churchill's actions.

The political impact on Churchill continued. In 1940, when the government was struggling, Clement Attlee secretly warned that the Labour Party might not support Churchill. This was because of his link to Tonypandy. In 1978, there was an uproar in Parliament. Churchill's grandson, also named Winston Churchill, was answering a question about miners' pay. The Labour leader James Callaghan warned him not to continue "the vendetta of your family against the miners of Tonypandy." In 2010, a Welsh local council objected to naming an old military base after Churchill. This was because he sent troops into the Rhondda Valley.

A Common Historical Mistake

The Tonypandy riots are part of a popular historical mistake. Many people believe that troops fired on the miners. Josephine Tey mentions this in her novel The Daughter of Time. She used the term "tonypandy" to describe when a historical event is reported incorrectly. This incorrect story is then believed to be the truth.

See also

- Llanelli railway strike, 1911

- National coal strike of 1912