Tsankawi facts for kids

Tsankawi is a special part of Bandelier National Monument in New Mexico. It's close to White Rock. You can get there from a parking area just off State Road 4. A 1.5-mile walking path lets you explore old ruins, caves dug into soft rock, and cool rock carvings called petroglyphs.

Contents

What Does Tsankawi Mean?

The name Tsankawi (pronounced san-KAH-wee) comes from the Tewa language. It might mean "village between two canyons where sharp, round cacti grow." Or, it could simply mean "prickly pear sharp gap." The San Ildefonso Pueblo people, who live nearby, speak Tewa.

A Look Back at Tsankawi's History

Ancient Pueblo people built Tsankawi. They are sometimes called the Ancestral Pueblo People. Experts believe Tsankawi was built in the 1400s. People lived there until the late 1500s. This was near the end of a time called the Rio Grande Classic Period.

Scientists used tree rings to learn about the past. They found that a big drought happened in the late 1500s. Many Tewa Pueblos nearby, like San Ildefonso, Santa Clara, Pojoaque, and Tesuque, say their ancestors lived at Tsankawi.

People first settled in this area in small groups around the late 1100s. Over time, they built fewer but larger communities. Tsankawi was one of these bigger villages. The walking paths you see today are centuries old. The Ancestral Pueblo people used them to travel.

The people of Tsankawi spoke Tewa. Those in Frijoles Canyon, another part of Bandelier, spoke Keres. Even though their languages were different, their beliefs and ways of life were similar. Today, pueblos like San Ildefonso and Cochiti still have strong ties to these old sites.

The 1.5-mile trail at Tsankawi follows these ancient paths. In some places, the paths are worn 8 to 24 inches deep into the rock. This shows how much people walked there. They traveled from the mesa tops to their farms in the canyons. They also connected to other villages. The people usually wore sandals or walked barefoot.

Most of Tsankawi has not been dug up by archaeologists. However, Edgar Hewett did dig up two burial mounds. He did this near the main village buildings in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Tsankawi Village Life

The village was built from a soft rock called tuff. The walls were covered with mud inside and out. It was shaped like a rectangle with about 350 rooms. There was a central courtyard or plaza inside. Rooms were used for cooking, sleeping, and storing food. This design, with rooms around a plaza, is still used by Pueblo people today.

The buildings were two or three stories tall. Their roofs were made of wood and mud. It's interesting that the village was on top of a mesa. Water had to be carried up from springs or rivers below. Rainwater was collected in a small reservoir. There is no clear sign of warfare, but more study is needed.

The people of Tsankawi depended completely on their environment. The climate was dry, with only about 15 inches of rain each year. Still, they learned to farm. They used local plants like pinion pine, juniper, and yucca for food, medicine, and tools. They also grew corn, beans, and squash.

Over time, natural resources became scarce. Firewood was hard to find, and the soil became tired from farming for centuries. A long drought in the 1500s forced the people to move. The people of San Ildefonso Pueblo, about 8 miles away, say their ancestors came from Tsankawi.

The people of Tsankawi were not alone. Many villages were on nearby mesas or in canyons. People traded tools, blankets, pottery, and food. They also gathered for religious events. The village plaza was likely a place for dancing and ceremonies.

Since there was no metal, tools were made from local materials. Obsidian, a volcanic glass, was used for arrow points and knives. Volcanic basalt was used to grind seeds and corn. It also helped them dig out caves and shape building blocks.

After the people left in the late 1500s, the buildings slowly fell apart. The roofs collapsed, and the walls crumbled. Wind blew dirt and debris into the cracks. Now, only mounds of rubble remain, with pieces of pottery on the ground.

Tsankawi Cave Homes

The ancient people of Tsankawi lived not only in the village on the mesa top. They also built homes along the base of the cliffs. They dug caves into the soft tuff rock. Then, they added walls made of loose stones and mud to extend their homes. These loose stones are called talus. The roofs were made of timber and mud. These homes are called talus pueblos.

About 354 talus pueblos have been found on Tsankawi Mesa. Most are where two different rock layers meet. Over time, the stone walls of these homes have fallen down. What remains are the caves, called cavates, and holes in the rock. These holes once held the wooden beams for the roofs.

Inside the caves, where they were protected from the weather, the walls are black. This is from fires used for cooking and warmth in winter. The talus pueblos were built on the south side of the mesas. In winter, the afternoon sun would warm these southern cliffs. This would melt the snow. But the north-facing cliffs often had snow all winter.

The walls were often covered with clay. This might have been for decoration or to keep the walls from crumbling. You can still see artwork on some cave walls. There are pictographs carved into the rock and bits of paint where clay still sticks.

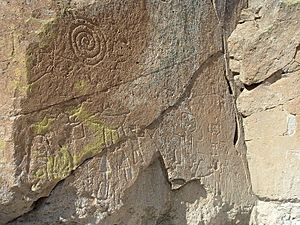

Tsankawi Rock Carvings

Many petroglyphs can be found around Tsankawi and throughout the Southwest. Petroglyphs are designs carved into stone. The ones here are on the cliffs and inside some cave homes. Sadly, they were carved into soft rock, which wears away easily. Many drawings are hard to see now or have disappeared.

Some meanings of these figures are known by modern-day Pueblo people. They are important to their culture. For other petroglyphs, we can only guess what the people were trying to say.

Among the petroglyphs are figures of people, animals, birds, and stars. Similar carvings can be found at Frijoles Canyon. There is also a large collection of petroglyphs south of Bandelier National Monument at Petroglyph National Monument.

Duchess Castle

To the northeast, you can see the remains of a home and school. A woman named Madame Vera von Blumenthal and her friend Rose Dougan built it in 1918. Madame von Blumenthal was actually a baroness, not a duchess. They taught local Pueblo potters how to bring back old pottery-making skills. Their goal was to make the pottery more valuable. This would help the Pueblo communities earn money.

How to Get to Tsankawi

The Tsankawi part of Bandelier National Monument is on State Highway 4. It is about twelve miles from the main part of the park. The GPS coordinates for the entrance are: 35.859, -106.224

Images for kids