Rhodesia's Unilateral Declaration of Independence facts for kids

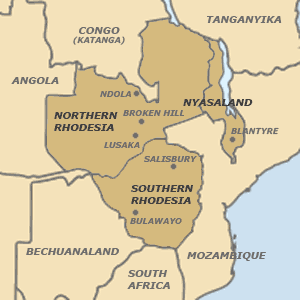

Quick facts for kids Unilateral Declaration of Independence |

|

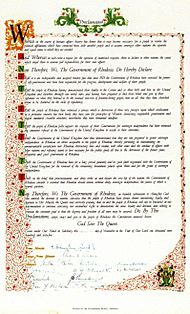

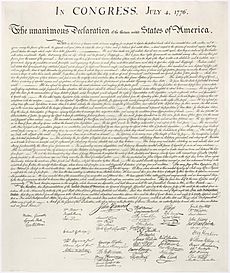

A scan of the proclamation document

|

|

| Created | November 1965 |

| Ratified | 11 November 1965 |

| Location | Salisbury, Rhodesia |

| Authors | Gerald B. Clarke et al. |

| Signers |

|

| Purpose | To announce and explain unilateral separation from the United Kingdom |

Rhodesia's Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) was a big announcement made by the government of Rhodesia on 11 November 1965. It said that Rhodesia, a British territory in southern Africa, was now an independent country. Rhodesia had been governing itself since 1923.

This declaration happened after a long disagreement between the British and Rhodesian governments. They couldn't agree on the rules for Rhodesia to become fully independent. It was the first time a British colony had declared independence on its own since the United States Declaration of Independence in 1776.

The United Kingdom (UK), the Commonwealth, and the United Nations (UN) all said Rhodesia's UDI was against the law. They put economic sanctions on Rhodesia. These were the first sanctions in the UN's history. Rhodesia became an unrecognised country. It got help from South Africa and Portugal (until 1974).

The Rhodesian government was mostly made up of white people, who were about 5% of the population. They were upset because other African colonies were becoming independent quickly in the early 1960s. These other colonies had less experience governing themselves. But Rhodesia was told it couldn't be independent until the black majority ruled. This was called "no independence before majority rule" (NIBMAR). Most white Rhodesians felt betrayed. They believed they deserved independence after 40 years of self-rule.

The leaders of Britain and Rhodesia, Harold Wilson and Ian Smith, disagreed a lot between 1964 and 1965. Britain wanted independence terms to be "acceptable to the people of the country as a whole." Smith said this was true, but the UK and black Rhodesian leaders disagreed. After Wilson suggested changes to Rhodesia's parliament, Smith and his government declared independence. The British governor, Sir Humphrey Gibbs, said this was treason and fired Smith's government. But they ignored him and appointed their own leader.

No country officially recognised UDI. However, the Rhodesian High Court said Smith's government was legal in 1968. Smith's government first said they were still loyal to Queen Elizabeth II. But in 1970, they declared Rhodesia a republic to try and get other countries to recognise them. This didn't work. The Rhodesian Bush War, a fight between the government and black groups, started in 1972. Smith eventually made a deal with some black leaders in 1978. This led to the country being called Zimbabwe Rhodesia in 1979, with black rule. But the war continued until Rhodesia cancelled its UDI in December 1979. After a short time under British rule, the country became independent as Zimbabwe in 1980.

Contents

Rhodesia's Unique Past

Rhodesia, officially called Southern Rhodesia, was special in the British Empire. Even though it was a colony, it governed itself. This started in 1923. Before that, a company called the British South Africa Company ran it for 30 years. Britain wanted Southern Rhodesia to join South Africa. But the people voted no in 1922. So, it became a self-governing colony, almost like a dominion. It could manage almost all its own matters, including defence.

On paper, Britain had a lot of power over Southern Rhodesia. The British Crown could cancel any law within a year. It could also change the constitution. These powers were meant to protect black Africans and British business. But in reality, Britain never used these powers. It would have caused big problems. Britain and the Rhodesian government usually worked well together.

The 1923 constitution said everyone could vote if they met certain standards. These standards were about income, education, and property. But most black people did not meet these standards. So, most voters and parliament members were white. Black people had very little say in government. White Rhodesians often felt black people were not ready to govern. Laws like the Land Apportionment Act of 1930 gave about half the land to white people.

White settlers were important for the country's economy. They provided skills in administration, industry, and farming. Rhodesia had a strong economy with farming, manufacturing, and mining. Daily life had some unfairness, like certain jobs being only for whites. But schools, healthcare, and wages for black Rhodesians were good compared to other African countries.

Southern Rhodesia was unique because it was "quasi-independent." The British office that dealt with countries like Australia and Canada also dealt with Southern Rhodesia. The Rhodesian Prime Minister even attended important meetings with leaders from other British territories. Rhodesians of all races fought for Britain in World War II. The government slowly got more control over its own foreign affairs.

After the war, many white people moved to Southern Rhodesia from Britain, Ireland, and South Africa. The white population grew from about 69,000 in 1941 to over 221,000 in 1961. The black population also grew a lot, from 1.4 million to 3.5 million. Rhodesian leaders wanted more white people. They hoped this would help them get more independence from Britain.

Joining and Leaving the Federation

Prime Minister Godfrey Huggins led Southern Rhodesia from 1933 to 1953. He thought full independence was easy to get. But he chose to create a Federation with Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland. These two were directly ruled by London. Huggins hoped this would lead to a big, united country in south-central Africa. The Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland started in 1953. Southern Rhodesia was the most developed part, and its capital, Salisbury, became the Federation's capital.

This Federation happened as many African countries were becoming independent. It was seen as unusual because Southern Rhodesia was self-governing, but the other two were directly ruled. Black people opposed the Federation from the start. It failed because of changing world views and growing hopes among black Rhodesians in the late 1950s and early 1960s. This period is often called the "Wind of Change." Britain, France, and Belgium quickly left Africa. They believed colonial rule was no longer right. The idea of "no independence before majority rule" (NIBMAR) became very popular in Britain.

When Huggins asked Britain to make the Federation a dominion in 1956, he was refused. The opposition party, the Dominion Party, often called for a unilateral declaration of independence (UDI) for the Federation. After Huggins retired, his replacement, Sir Roy Welensky, thought about UDI several times.

To push for Southern Rhodesian independence, Prime Minister Sir Edgar Whitehead worked with Britain on the 1961 constitution. He believed this would remove all British power over Rhodesian laws. He thought it would make Rhodesia almost fully independent. Even though it didn't promise independence, Whitehead and Welensky told Rhodesian voters it was the "independence constitution." White voters approved it in a referendum in 1961.

However, the final constitution had a hidden part, Section 111. This section allowed the British Crown to change or cancel parts of the Rhodesian constitution. This meant Britain still had power, but Rhodesians didn't notice it at first.

Black Rhodesian groups were often banned by the government. They were involved in political violence and intimidation. The main group, led by Joshua Nkomo, changed its name often. By 1962, it was called the Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU). Whitehead tried to make changes to unfair laws. But ZAPU's actions made it hard for him to get black support. Many white people thought Whitehead was too soft on black groups. In the December 1962 election, Whitehead's party lost to the Rhodesian Front (RF). This was a surprise. Winston Field became Prime Minister, with Ian Smith as his deputy.

End of the Federation; Growing Mistrust

Meanwhile, black parties won elections in Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland. Britain decided to break up the Federation. In February 1962, Britain secretly told Nyasaland's leader, Hastings Banda, that it could leave. A few days later, a British official told Welensky, "we British have lost the will to govern." Welensky's minister replied, "But we haven't."

Britain officially announced Nyasaland's right to leave in December 1962. Four months later, Britain said it would hold a meeting to decide the Federation's future. Southern Rhodesia had helped create the Federation. So, Britain needed its cooperation to end it. Field could have refused to attend the meeting until Britain promised independence.

Field, Smith, and other RF politicians said British officials promised them independence if they cooperated. But Britain refused to put anything in writing. They said a written promise would go against the "spirit of trust" in the Commonwealth. Field eventually accepted this. Smith warned them, "if you break that you will live to regret it." Southern Rhodesia attended the meeting in June 1963. They agreed to end the Federation by the end of the year. Later, in the British Parliament, officials denied making any secret promises.

In October 1963, Britain announced that Nyasaland would become fully independent in July 1964. Northern Rhodesia was expected to follow soon. Smith went to London for independence talks. But they didn't lead anywhere. Around this time, Rhodesians realised Section 111 of the 1961 constitution meant Britain could still interfere. They worried what the Labour Party might do if it won the next British election. So, Rhodesians tried harder to get independence before that election. The Federation ended as planned at the end of 1963.

Why Rhodesia Declared Independence

Britain's Viewpoint

Britain refused to give Southern Rhodesia independence because of the "Wind of Change." This was about global changes and new ideas about right and wrong. Britain also wanted to avoid being criticised by the United Nations (UN) and the Commonwealth. The world saw Rhodesia as a symbol of decolonisation and racism. By the early 1960s, the UN strongly opposed all forms of colonialism. It supported black nationalist groups in Africa.

Britain didn't want the Soviet Union or China to gain influence in Africa. But it knew it would be seen as bad if it didn't support NIBMAR for Southern Rhodesia. When the UN and other groups, like the Organisation of African Unity (OAU), started talking about Southern Rhodesia, even keeping things as they were became a problem. This caused Britain a lot of embarrassment.

Many Afro-Asian countries in the Commonwealth were also against giving Rhodesia independence without majority rule. If Britain did, the Commonwealth might break up. This would be terrible for British foreign policy. Britain tried to find a middle ground. But in the end, it put international concerns first.

The Labour Party in Britain was strongly against Southern Rhodesian independence under the 1961 constitution. They supported the black Rhodesian movement. The Liberal Party agreed. The Conservative Party was more understanding of the Rhodesian government.

Rhodesia's Viewpoint

The Rhodesian government found it strange that Britain was making Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland independent. These countries were less developed and had less experience governing themselves. But Southern Rhodesia, the most developed part of the Federation, was denied independence. It had been self-governing for 40 years.

Rhodesians thought the idea of majority rule was not important. They believed they would get independence after the Federation ended. They felt Britain had promised this. When it didn't happen, they felt tricked. Salisbury argued that its mostly white government deserved independence more. They had proven they could govern well for decades.

The Rhodesian Front (RF) said that many new black-ruled African countries had problems. They had civil wars, coups, and became one-party states. The RF used this to say black Rhodesian leaders were not ready to govern. They worried about what black rule might mean for white people. They said the voting system was fair because it was based on money and education, not race. They pointed out Rhodesia's help to Britain in wars. They wanted to be an anti-communist country with South Africa and Portugal.

These reasons, plus what RF politicians saw as Britain's unfairness, made them believe UDI was necessary. They thought it was for the good of their country, even if it caused international problems.

Steps Towards Independence

Under Winston Field

Field's failure to get independence made his government lose trust in him. In January 1964, the RF party showed they were unhappy. They felt Britain was outsmarting Field. He was under great pressure to get independence. Field went to England in January to talk to British leaders. He mentioned UDI a few times but came back without a deal.

The RF united behind Field after Britain warned them about UDI. But then Field lost his party's trust again. He didn't follow a plan to get independence. This plan involved asking the Queen to change the 1961 constitution. This would stop Britain from interfering. The RF wanted to see if Britain would block this. But Field was persuaded not to send it to the Governor.

Lord Salisbury, a supporter of Rhodesia in Britain, was upset. He said the best time to declare independence was when the Federation ended. The RF leaders saw Field's actions as a sign he wouldn't challenge Britain. So, they forced him to resign on 13 April 1964. Ian Smith became the new Prime Minister.

Ian Smith Takes Charge

Ian Smith was Rhodesia's first Prime Minister born in the country. He was a farmer who had fought in World War II. He was seen as a "raw colonial" by British politicians. Smith promised to be tougher in independence talks. He said he wanted a middle path between black rule and apartheid. He wanted a place for white people in Rhodesia, saying it would help black people too. He believed government should be based on "merit, not on colour or nationalism." He insisted there would be "no African nationalist government here in my lifetime."

Rhodesia's refusal to follow the "Wind of Change" led to problems. Its usual suppliers of military equipment, Britain and America, stopped sending supplies. Britain and Washington also stopped financial aid. In June 1964, Britain told Smith that Rhodesia would not be at the Commonwealth Prime Ministers' Conference. Rhodesia had attended since 1932. Britain said only fully independent states could attend now. This decision insulted Smith deeply.

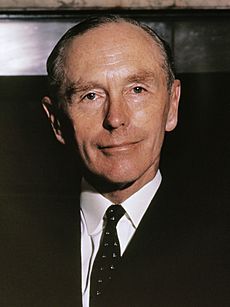

In September 1964, British Prime Minister Sir Alec Douglas-Home and Smith disagreed on how to measure black public opinion in Rhodesia. Britain said independence terms had to be "acceptable to the people of the country as a whole." Smith suggested a referendum for white and urban black voters. For rural black views, he suggested a national indaba (tribal conference) of chiefs. Douglas-Home liked the idea but said the Commonwealth, UN, or Labour Party wouldn't accept it. He said it might hurt the Conservatives in the upcoming British election. Smith agreed to wait. Douglas-Home promised that a Conservative government would grant independence within a year.

Smith then organised the indaba for 22 October and a general independence referendum for 5 November 1964. Meanwhile, Wilson wrote to black Rhodesians. He promised that the Labour Party would not grant independence as long as white minority ruled.

Wilson's Labour Government; Rhodesia's Opinion Tests

The Labour Party won the British election on 15 October 1964. Both Labour and the Conservatives told Smith that the indaba results would not be accepted. Smith went ahead with it. On 22 October, 196 chiefs and 426 headmen met near Salisbury. Smith hoped Britain would send observers, but they didn't.

On 24 October 1964, Northern Rhodesia became independent Zambia. Nyasaland had become Malawi three months earlier. Southern Rhodesia then started calling itself simply Rhodesia. The same day, the head of the Rhodesian Army resigned. He said he was against UDI because of his loyalty to the Queen. Wilson wrote to Smith, warning him about UDI. Smith ignored it.

The indaba ended on 26 October. The chiefs and headmen all supported independence under the 1961 constitution. They said people far away didn't understand their country's problems. Black nationalist groups rejected this, saying the chiefs were paid by the government. Britain ignored the indaba. On 27 October, Wilson warned that UDI would lead to Rhodesia losing its ties with Britain, the Commonwealth, and most of the world. He said sanctions would be imposed. This was meant to stop white Rhodesians from voting for independence. On 5 November 1964, 89% of Rhodesia's mostly white voters said "yes" to independence. Smith said this met Britain's condition of acceptability.

Smith and Wilson Disagree

Smith asked Wilson to send a British official for talks. Wilson said Smith should come to London instead. They exchanged angry letters for months. Wilson's representative in Salisbury hinted that UDI would affect financial aid. Smith was furious, calling it blackmail. He wrote to Wilson, saying Britain's actions made it impossible to negotiate.

The two leaders met in London in January 1965. They disagreed on most things. But they agreed that British officials would visit Rhodesia to see public opinion. These officials visited from 22 February to 3 March. They reported that they hoped to find a solution for independence and prosperity for all Rhodesians. They also spoke against violence between black groups.

The RF called a new election for May 1965. They promised independence and won all 50 seats for mostly white voters. Josiah Gondo became the first black opposition leader. On 9 June, the Governor said the RF's win meant they had a right to lead the country to independence. He announced Rhodesia would open its own office in Lisbon, Portugal. Britain and Rhodesia argued about this. Portugal accepted the mission in September, making Britain angry. Wilson's ministers tried to delay talks to pressure Smith. Rhodesia was again excluded from the Commonwealth meeting. Smith felt Rhodesia was being pushed away. He accused Britain of "politics of convenience and appeasement." Wilson found Rhodesia inflexible. He said the two governments were "between different worlds and different centuries."

Final Steps to UDI

Wilson: We are not giving up. Too much is at stake ... I know I speak for everyone in these islands, all parties, all our people, when I say to Mr Smith, 'Prime Minister, think again'.

Smith: After 43 years of proving our case we are told that we cannot be master in our own house. Is it not incredible that the British government has allowed our case to deteriorate into this fantastic position? ... I believe I should say to Mr Wilson: 'Prime Minister, think again!'

Rumours of UDI grew stronger. Smith went to London in October 1965 to solve the independence issue. Many Britons supported Smith during his visit. Smith tried to appear on the BBC, but the British government stopped it. After talks with Wilson failed, Smith flew home on 12 October. Wilson then went to Salisbury two weeks later to continue talks.

During these talks, Smith often mentioned UDI as a last resort. He offered to let more black people vote if Britain granted independence. Wilson said this wasn't enough. He suggested Britain could control Rhodesia's parliament to ensure black representation. Rhodesians were shocked. They felt Wilson was taking away their options. Before Wilson left on 30 October 1965, he suggested a Royal Commission. This commission would check public opinion on independence.

The Rhodesian government decided its only choices were to trust the Royal Commission or declare independence. When they saw the terms for the commission, they found it would assume the 1961 constitution was unacceptable to Britain. Also, Britain wouldn't promise to accept the report. Smith rejected these terms. He wrote to Wilson on 5 November, saying Wilson had "finally closed the door."

The Rhodesian government declared a state of emergency on 5 November. They said black Rhodesian fighters were entering the country. Smith denied this meant UDI was coming. But his letter to Wilson was published, causing worldwide talk of UDI. On 8 November, Smith asked Wilson again to appoint the Royal Commission under their agreed terms. Wilson didn't reply right away. On 9 November, the Rhodesian government sent a letter to Queen Elizabeth II. They promised to remain loyal to her "whatever happens."

The Declaration of Independence

The Rhodesian Minister of Justice, Desmond Lardner-Burke, showed a draft of the declaration of independence to the government on 5 November 1965. Other ministers also had drafts. They decided that if they declared independence, everyone would sign it. On 9 November, they planned out the document and Smith's speech. The final declaration was written by civil servants. They used the United States Declaration of Independence from 1776 as a guide. They even used the phrase "a respect for the opinions of mankind" exactly. But they left out "all men are created equal" and "consent of the governed."

With the declaration came a changed version of the 1961 constitution. This became the 1965 constitution. Smith's government believed this made Rhodesia truly independent. They still said they were loyal to Queen Elizabeth II. The new constitution created a new position, the Officer Administering the Government. This person would sign laws if the Queen didn't appoint a Governor-General.

The Rhodesian government waited for Wilson's reply on 9 and 10 November, but it didn't come. On the evening of 10 November, a British official warned Wilson that Rhodesia seemed ready to declare independence. Wilson tried to call Smith. He finally reached him on 11 November at 8:00 AM. Smith was already in a meeting about independence. Wilson tried to talk him out of it. Smith told his ministers about the call. They decided Wilson was just trying to buy time. Smith asked each minister if Rhodesia should declare independence. They all said "Yes."

At 11:00 AM on 11 November 1965, Armistice Day, Smith declared Rhodesia independent. He signed the document, followed by his deputy and 10 other ministers. The timing was chosen to remember Rhodesia's sacrifices for Britain in past wars. Smith and his ministers still pledged loyalty to Queen Elizabeth II. Her portrait was behind them as they signed. The declaration ended with "God Save The Queen."

What the Declaration Said

Proclamation

Whereas in the course of human affairs history has shown that it may become necessary for a people to resolve the political affiliations which have connected them with another people and to assume amongst other nations the separate and equal status to which they are entitled:

And Whereas in such event a respect for the opinions of mankind requires them to declare to other nations the causes which impel them to assume full responsibility for their own affairs:

Now Therefore, We, The Government of Rhodesia, Do Hereby Declare:

That it is an indisputable and accepted historic fact that since 1923 the Government of Rhodesia have exercised the powers of self-government and have been responsible for the progress, development and welfare of their people;

That the people of Rhodesia having demonstrated their loyalty to the Crown and to their kith and kin in the United Kingdom and elsewhere through two world wars, and having been prepared to shed their blood and give of their substance in what they believed to be the mutual interests of freedom-loving people, now see all that they have cherished about to be shattered on the rocks of expediency;

That the people of Rhodesia have witnessed a process which is destructive of those very precepts upon which civilization in a primitive country has been built, they have seen the principles of Western democracy, responsible government and moral standards crumble elsewhere, nevertheless they have remained steadfast;

That the people of Rhodesia fully support the requests of their government for sovereign independence but have witnessed the consistent refusal of the Government of the United Kingdom to accede to their entreaties;

That the Government of the United Kingdom have thus demonstrated that they are not prepared to grant sovereign independence to Rhodesia on terms acceptable to the people of Rhodesia, thereby persisting in maintaining an unwarrantable jurisdiction over Rhodesia, obstructing laws and treaties with other states and the conduct of affairs with other nations and refusing assent to laws necessary for the public good, all this to the detriment of the future peace, prosperity and good government of Rhodesia;

That the Government of Rhodesia have for a long period patiently and in good faith negotiated with the Government of the United Kingdom for the removal of the remaining limitations placed upon them and for the grant of sovereign independence;

That in the belief that procrastination and delay strike at and injure the very life of the nation, the Government of Rhodesia consider it essential that Rhodesia should attain, without delay, sovereign independence, the justice of which is beyond question;

Now Therefore, We The Government of Rhodesia, in humble submission to Almighty God who controls the destinies of nations, conscious that the people of Rhodesia have always shown unswerving loyalty and devotion to Her Majesty the Queen and earnestly praying that we and the people of Rhodesia will not be hindered in our determination to continue exercising our undoubted right to demonstrate the same loyalty and devotion, and seeking to promote the common good so that the dignity and freedom of all men may be assured, Do, By This Proclamation, adopt, enact and give to the people of Rhodesia the Constitution annexed hereto;

God Save The Queen

Given under Our Hand at Salisbury, this eleventh day of November in the Year of Our Lord one thousand nine hundred and sixty-five.

- Prime Minister: Ian Smith

- Deputy Prime Minister: Clifford Dupont

- Ministers: William Harper, Montrose, Phillip van Heerden, Jack Howman, Jack Mussett, John Wrathall, Desmond Lardner-Burke, George Rudland, Ian McLean, Arthur Philip Smith

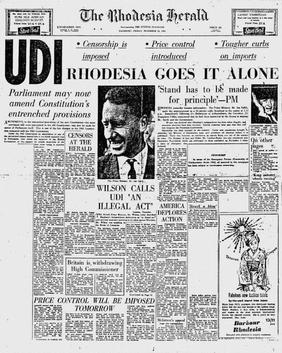

Announcing UDI and Reactions

The Announcement

The Rhodesian Broadcasting Corporation told everyone to wait for an important announcement from the Prime Minister. Smith first went to Government House to tell Governor Gibbs about the independence. Then he went to the studios to announce UDI to the country. He read the declaration. He said independence was declared because Britain had no real intention of finding a solution Rhodesia could accept. Smith said he had tried to negotiate until the very end.

Smith said he felt he had to act. He didn't want Rhodesia to keep drifting in uncertainty. He claimed UDI would not reduce opportunities for black people to advance. He spoke about "racial harmony in Africa." He criticised black Rhodesian groups for trying to "blackmail the British government." He tried to calm fears about economic sanctions. He asked Rhodesians to be strong. He said Rhodesia was the first Western nation in 20 years to say "so far and no further." He ended by saying the declaration was "a blow for the preservation of justice, civilisation and Christianity."

Reactions in Rhodesia

When Smith and Dupont arrived at Government House, Britain had already told Governor Gibbs to fire Smith and his ministers for treason. Gibbs did this. But Smith and his ministers ignored him. They said Gibbs no longer had power under the new 1965 constitution. Gibbs told the Rhodesian military officers to stay at their jobs to keep order.

The Rhodesian government took emergency steps. They said this was to prevent panic and people leaving. They censored the press and rationed petrol. News of UDI was mostly calm. Some people were arrested, like Leo Baron, a lawyer linked to black Rhodesians.

Roy Welensky, who was against UDI, said it was still every Rhodesian's duty to support the new government. He believed the only other choice was chaos. The Portuguese consul-general in Salisbury was very excited. He said, "Only Rhodesians could do this!" Black nationalist leaders called UDI an act of "treason and rebellion." They said it put the lives of four million black Africans at risk. Most Christian leaders in Rhodesia rejected UDI.

A week after UDI, Smith's government announced that Clifford Dupont would become the Officer Administering the Government. Smith asked the Queen to appoint Dupont as Governor-General. The Queen ignored this. Britain said Gibbs was still the only legal representative of the Queen in Rhodesia. Dupont still took over Gibbs's role. He was given the Governor's official residence. But Gibbs and his staff were not forced to leave. The new government said Dupont would live elsewhere until Government House was "available."

The Speaker of the Rhodesian parliament, A R W Stumbles, restarted parliament on 25 November. He feared chaos if he didn't. One white opposition MP, Ahrn Palley, said the parliament was illegal. He was forced out, shouting, "This is an illegal assembly! God save the Queen!" Other opposition MPs also left but rejoined later.

Gibbs received threats. On 26 November 1965, Smith's government cut off his phones and took away his guards and cars. But Gibbs refused to leave Government House. He stayed there, ignored by the new government, until 1970.

Britain's Response and Sanctions

Wilson was shocked by Smith's actions. He found the timing of the declaration, during the Armistice Day silence, very insulting. Wilson told Rhodesians to ignore Smith's government. Within hours of UDI, the UN General Assembly passed a resolution condemning Rhodesia. It called on Britain to end the "rebellion." The UN Security Council also said UDI was illegal and racist. It told all countries not to recognise or help the Rhodesian government.

Rhodesian nationalist groups wanted Britain to use force to remove Smith's government. But Britain said this was too risky. It could lead to a war between British and Rhodesian troops. Wilson decided to end the rebellion using economic sanctions. These included kicking Rhodesia out of the Sterling area. They banned imports of Rhodesian sugar, tobacco, and chrome. They also boycotted oil to Rhodesia.

When Rhodesia kept getting oil, Wilson tried to block their main supply lines. These were the Portuguese ports in Mozambique. The British Navy set up a blockade in the Mozambique Channel in March 1966. The UN supported this blockade. The UN then put the first mandatory trade sanctions in its history on Rhodesia. This meant member countries had to stop all trade with Rhodesia.

Wilson thought sanctions would make Smith give up in "weeks rather than months." But the sanctions didn't hurt Rhodesia much at first. This was because South Africa and Portugal kept trading with Rhodesia. They provided oil and other goods. Secret trade with other countries also continued. Rhodesian businesses slowly grew. Rhodesia became more self-sufficient. The Rhodesian government set up companies in other countries to help trade. Even many OAU states, while criticising Rhodesia, kept buying Rhodesian food. The United States even allowed imports of Rhodesian chrome from 1971 to 1977.

Recognition and Legal Status

International Recognition Efforts

Official recognition from other countries was very important for Rhodesia. It was the only way to get back the international standing it lost. Smith hoped Britain would recognise them. This would end sanctions and make other Western countries accept them. The Rhodesian Front thought some Western countries might recognise UDI anyway. They hoped for recognition from South Africa and Portugal. They also thought France might recognise Rhodesia to annoy Britain. But no country ever officially recognised Rhodesia as an independent state.

Britain removed most of its staff from Salisbury after UDI. Some countries closed their offices in Salisbury. But the United States kept its office, calling it a "US Contacts Office." South Africa and Portugal kept their offices, which were like embassies. Rhodesia also kept its offices in Pretoria, Lisbon, and Lourenço Marques. Rhodesia also had unofficial offices in the US, Japan, and West Germany. The Rhodesian office in London, Rhodesia House, became its main office in the UK. It was often a target for protests.

Many countries kept their offices in Rhodesia because they said their staff were accredited to the Queen, not Smith's government. But Rhodesia moved away from being a monarchy. In March 1970, after a vote, Smith's government declared Rhodesia a republic. This was meant to get official recognition. But it had the opposite effect. All countries except Portugal and South Africa closed their offices. After a revolution in Portugal in 1974, Rhodesia's offices there closed. South Africa was the only country left with links to Salisbury.

Legal Rulings in Rhodesia

The Rhodesian High Court judges at first didn't say UDI was right or wrong. The Chief Justice, Sir Hugh Beadle, said judges would keep doing their jobs "according to the law." Over time, their stance changed.

In 1966, a case called Madzimbamuto v. Lardner-Burke came up. It was about Daniel Madzimbamuto, a black Rhodesian. He was held without trial by the Rhodesian government. His wife argued that his imprisonment was illegal because Britain had said UDI was illegal.

In September 1966, the High Court said Britain still had legal power. But to "avoid chaos," the Rhodesian government was in control of law and order. In February 1968, Beadle ruled that Smith's government was the de facto (in fact) government because it controlled the country. But he said it wasn't de jure (by law) recognised.

Later in February 1968, Beadle ruled that Salisbury could carry out death sentences. Britain announced that the Queen had changed three death sentences to life imprisonment. But Beadle said this was a decision by the UK government, not the Queen. He said the Rhodesian government was the only power that could decide on mercy. Three men were hanged on 6 March. A judge resigned in protest.

On 23 July 1968, the British Privy Council in London ruled that Madzimbamuto was illegally held. It said the 1965 constitution was illegal. But on 8 August, a Rhodesian judge said Rhodesian courts would not follow this ruling. Another judge resigned in protest.

On 13 September 1968, the Rhodesian High Court fully recognised Smith's government as de jure. Beadle said the court had to choose between the 1965 constitution and legal chaos. He said sanctions would not overthrow the government. A judge, Hector Macdonald, argued that Britain had acted illegally by involving the UN in a domestic problem. He said Britain had given up its right to Rhodesian loyalty by waging economic war. So, UDI and the 1965 constitution were now considered legal by the Rhodesian courts.

New National Symbols

After UDI, Rhodesia slowly removed British symbols. They replaced them with symbols that felt more Rhodesian. A silver "Liberty Bell" was made in 1966. The Prime Minister rang it 12 times each year on Independence Day.

The British flag and Rhodesia's old flag (a blue flag with the British flag in the corner) flew over government buildings until 11 November 1968. Then, a new national flag was adopted. It was a green-white-green flag with the Rhodesian coat of arms in the middle. The British flag was still raised on Pioneers' Day, which celebrated Salisbury's founding.

Until 1970, Smith's government still saw Queen Elizabeth II as the head of state. "God Save the Queen" remained the national anthem. This was meant to show loyalty to the Queen. But it seemed strange. In 1974, after four years without an anthem, Rhodesia adopted "Rise, O Voices of Rhodesia". This song used the tune of Beethoven's "Ode to Joy". The country's new head of state was the President of Rhodesia, with Dupont as the first.

Press censorship, which started with UDI, ended in April 1968. In February 1970, Rhodesia changed its money system. The new Rhodesian dollar replaced the pound. After Rhodesia became a republic, the military removed references to the Crown. The Royal Rhodesian Air Force dropped "Royal." New flags were designed. The St Edward's Crown on emblems was replaced by the "Lion and Tusk." This symbol came from the British South Africa Company. New Rhodesian honours and medals were created. The police force, the British South Africa Police, kept its name.

Ending UDI

In January 1966, Wilson said he would not talk to Rhodesia's "illegal regime" until it gave up its independence claim. But by mid-1966, British and Rhodesian officials were having "talks about talks." Wilson later agreed to meet Smith. They tried to settle things on British warships in 1966 and 1968, but failed.

After the Conservatives won power in Britain in 1970, a deal was almost made in 1971. A Royal Commission then went to Rhodesia to see if the proposals were acceptable to most people. It found that most black people rejected them. So, the deal was dropped.

The Rhodesian Bush War, a fight between the Rhodesian Security Forces and black nationalist groups, began in December 1972. In 1974, a revolution in Portugal changed things. Portugal's support for Smith ended. Mozambique, Rhodesia's neighbour, became independent and Marxist. This helped the nationalist groups. Sanctions on Rhodesia finally started to hurt.

Diplomatic isolation, sanctions, the war, and pressure from South Africa made the Rhodesian government talk to black Rhodesian groups. Meetings were held in 1975 and 1976, but they failed. In late 1976, the two main black nationalist groups, ZANU and ZAPU, joined as the "Patriotic Front" (PF).

By the mid-1970s, it was clear that white minority rule could not last. Smith, who was re-elected three times, eventually agreed. In September 1976, he accepted the idea of "one man, one vote." In March 1978, he made a deal with black nationalist groups not involved in the fighting. This deal was called the Internal Settlement.

This settlement led to multiracial elections. Rhodesia became Zimbabwe Rhodesia in June 1979, with black majority rule. Bishop Abel Muzorewa became the country's first black Prime Minister. But the Patriotic Front rejected this new government. The war continued until December 1979. Then, Britain, Salisbury, and the Patriotic Front made a deal at Lancaster House.

Muzorewa's government cancelled UDI. This ended Rhodesia's claim to independence after 14 years. The UK took control for a short time. Then, new elections were held in 1980. ZANU won, and its leader, Robert Mugabe, became Prime Minister. The UK granted independence to Zimbabwe in April 1980. Black nationalist politicians continued to use their opposition to UDI to support their rule in Zimbabwe.

Images for kids

-

Ian Smith replaced Winston Field as Southern Rhodesian Prime Minister in April 1964, and pledged to challenge Britain on independence.

-

UK Prime Minister Sir Alec Douglas-Home met Smith in London in September 1964.

-

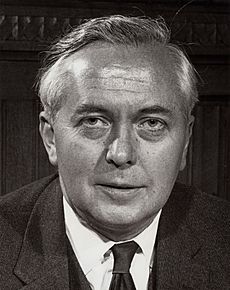

Harold Wilson replaced Douglas-Home in October 1964, and proved a formidable opponent of Smith.

-

10 Downing Street, where Wilson received Smith in January 1965.

-

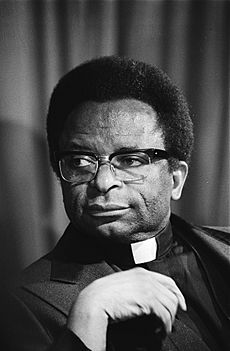

Bishop Abel Muzorewa, the country's first black Prime Minister, whose unrecognised government revoked UDI in 1979 as part of the Lancaster House Agreement.

See also