Unionism in Ireland facts for kids

Unionism in Ireland is a political idea. It means wanting to stay part of the United Kingdom. People who support unionism are loyal to the British King or Queen. They also support the laws and government of the UK.

Most Protestant people in Ireland have supported unionism. After 1829, unionists worked to stop Ireland from having its own parliament again. Since Ireland was divided in 1921, unionism has focused on Northern Ireland. It wants Northern Ireland to stay part of the UK. It also wants to stop Northern Ireland from joining the Republic of Ireland.

After years of conflict, the Good Friday Agreement was signed in 1998. Unionists now share power with Irish nationalists in Northern Ireland's government. But today, they are not working with nationalists. They are protesting new trade rules after Brexit. They feel these rules are pushing Northern Ireland away from Great Britain.

Unionism became a strong political movement in Ireland. This happened because the British government seemed to give in to Irish nationalists. At first, farmers who were Presbyterian and Liberals joined with Anglican Orange Order Conservatives. They all opposed the Irish Home Rule Bills of 1886 and 1893. These bills would have given Ireland more self-government.

Before World War I, this group grew stronger. It included loyalist workers. This movement became known as Ulster Unionism. It was strongest in Belfast and nearby areas. They even prepared to fight with weapons, forming the Ulster Volunteers.

In 1921, Ireland was divided. The rest of Ireland became a separate country. But Ulster Unionists agreed that the six counties in the northeast would stay in the UK. This area became Northern Ireland. For 50 years, the Ulster Unionist Party governed Northern Ireland. They had a lot of power and faced little opposition.

In 1972, the British government stopped this arrangement. There was a lot of political violence. The government wanted to find ways to include Catholics in Northern Ireland's public life. So, they closed the parliament in Belfast.

For the next 30 years, this period was called The Troubles. Unionists had different ideas about sharing power. British governments, working with the Republic of Ireland, offered new plans. After the 1998 Belfast Agreement, peace groups stopped fighting. Unionists agreed to share government roles. They also agreed to make decisions together in the new Northern Ireland Assembly.

The power-sharing system was updated in 2006. But relations are still difficult. Unionists have less support in elections now. They say their nationalist partners are pushing an anti-British culture. After Brexit, they also say the new trade rules, called the Northern Ireland Protocol, harm Northern Ireland's place in the UK.

Who Are Unionists?

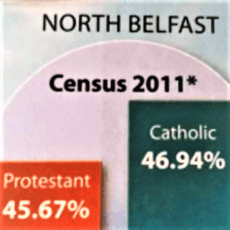

The number of people who identify as Protestant or were raised Protestant has changed. It has fallen from 60% in the 1960s to 48% today. At the same time, those raised Catholic have increased from 35% to 45%. This change in population numbers is important for unionists.

For example, in 2019, Nigel Dodds, a unionist, lost his seat in North Belfast. He had held it for 19 years. The winner was John Finucane from Sinn Féin, a nationalist party. Arlene Foster, a unionist leader, said the population numbers were against them. A Sinn Féin flyer from 2015 showed that Catholics were now a slightly larger group in that area. It told Catholic voters to "Make the change."

Today, only two of Northern Ireland's six counties, Antrim and Down, have many Protestants. Only one city, Lisburn, has a Protestant majority. Most Protestants now live in the areas around Belfast. Unionist support has also gone down. In elections since 2014, the total unionist vote has been below 50%. In the 2019 election, it was only 42.3%.

However, fewer unionist votes do not always mean more nationalist votes. The total nationalist vote is still below 41.8%, which it reached in 2005. Even though nationalists won more MPs in 2019 and Sinn Féin became the largest party in Stormont in 2022, their overall vote has not grown much.

Surveys show that many people in Northern Ireland, about 50%, say they are neither unionist nor nationalist. These people are often younger. They are also less likely to vote in elections that are still very divided. It is still rare for Protestants to vote for nationalists, or for Catholics to vote for unionists. But people will vote for other parties. These parties do not focus on whether Northern Ireland should stay in the UK or join Ireland.

The main "other" party is the Alliance Party of Northern Ireland. In 2019, Alliance greatly increased its votes. In the May European elections, their vote went from 7.1% to 18.5%. In the December Westminster election, it went from 7.9% to 16.8%. In the 2022 Assembly election, Alliance got 13.5% of the first-choice votes. They ended up with almost a fifth of the Assembly seats.

Surveys after the 2019 election showed that Alliance gained voters from both unionist and nationalist parties. Alliance is neutral on the question of Northern Ireland's future. But a 2020 survey found that more Alliance voters (47%) would choose to join Ireland than stay in the UK (22%) if there was a vote.

Some unionists have called for their movement to reach beyond its Protestant base. Peter Robinson, a former DUP leader, said he would not ignore 40% of the population. Surveys have suggested that some Catholics might vote for Northern Ireland to stay in the UK. These are "functional unionists." They might not like the "unionist" label, but they prefer to stay in the UK. However, very few members of the DUP and UUP parties are Catholic.

Protecting Unionist Culture

In 1994, the Downing Street Declaration said that both nationalist and unionist goals were equally valid. This meant that no one in Northern Ireland was "disloyal."

Unionists felt that nationalists used this idea to cause problems. David Trimble, a unionist leader, said there was a "slow attack" on the British culture of Ulster people. He blamed the IRA and their supporters. Peter Robinson and Arlene Foster also spoke of fighting back against Sinn Féin's efforts. They said Sinn Féin was trying to promote Irish culture and remove British symbols.

Unionists claimed that nationalist parties were working together. They said these parties were using public order rules to ban or change the routes of traditional Orange marches. For Trimble, a big issue was the Drumcree conflict (1995-2001). For Robinson and Foster, it was the Ardoyne shopfronts standoff (2013-2016) in north Belfast. Another protest happened in 2012. The Belfast City Council, once strongly unionist, decided to fly the Union Flag less often at City Hall. Unionists saw this as part of a "cultural war" against "Britishness."

Language rights became a major topic in talks between parties. In 1998, Prime Minister Tony Blair was surprised by a last-minute demand. Unionists wanted recognition for a "Scottish dialect" spoken in parts of Northern Ireland. They saw this Ulster Scots language as equal to the Irish language. Trimble believed this would help them in the "cultural war." Unionists argued that nationalists were using the Irish language to "attack" Protestants.

Nelson McCausland, a DUP minister, said that giving special status to Irish through a language law would be "ethnic marking." He and his party resisted Sinn Féin's demand for an Irish Language Act. They insisted on including Ulster Scots in any language law. This became a main reason why it took three years to get the power-sharing government working again in 2020.

Some other unionists disagree with this approach. They say that focusing on parades, flags, and language as a "counteroffensive" might make unionist culture seem less important. They worry it could be absorbed into Irish culture.

The 2020 New Decade New Approach agreement promised new Commissioners for both the Irish language and Ulster-Scots. These Commissioners would help develop the languages. However, the agreement did not give them equal legal status. The UK government recognized Scots and Ulster Scots as minority languages. This was for "encouragement" and "facilitation" under one European agreement. But for Irish, it took on stronger duties for education, media, and government use.

The agreement also took a step for Ulster Scots that it did not take for Irish speakers. The UK government promised to recognize Ulster Scots as a "national minority." This is under another European treaty. This treaty was previously used for non-white groups, Irish Travellers, and Roma in Northern Ireland. If unionists identify with Ulster Scots, they are, in a way, defining themselves as an ethnic group.

In 2022, the UK Parliament passed the law for New Decade New Approach. This happened even though unionists were protesting the Northern Ireland Protocol. The Identity and Language (Northern Ireland) Act became law on December 6.

Unionist Political Groups

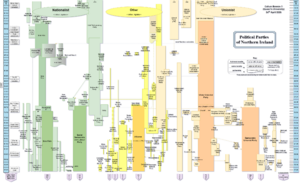

- Irish Conservative Party (1835–1891)

- Irish Unionist Alliance (1891–1922)

- Ulster Unionist Party (1905/1921–present)

- Democratic Unionist Party (1971–present)

- Progressive Unionist Party (1978–present)

- Traditional Unionist Voice (2007–present)

Images for kids

-

Detail of the Battle of Ballynahinch 1798 by Thomas Robinson. Government soldiers prepare to hang a rebel.

-

Flag of the Congested Districts Board for Ireland, 1893–1907.

-

The Coat of Arms of the Government of Northern Ireland (1924-1974).

-

The statue of Lord Edward Carson in front of Parliament Buildings, Stormont.