United States Army World War I Flight Training facts for kids

The United States Army started training pilots in 1909. This was after they bought their first airplane from the famous Orville and Wilbur Wright. This article tells you about how pilots were trained from those early days, through World War I, and up until 1926. That's when the United States Army Air Corps Flight Training Center opened in San Antonio, Texas.

Contents

- First Flight Lessons: Early Army Aviation

- World War I Flight Training: A Big Boost

- Images for kids

First Flight Lessons: Early Army Aviation

The very first flight training for the U.S. military began on October 8, 1909. Wilbur Wright taught Lieutenants Frank P. Lahm and Frederic E. Humphreys how to fly. They learned on the Army's first plane, which was bought from the Wright brothers. Each man got about three hours of training before flying solo on October 26, 1909.

The Army first tested airplanes at Fort Myer, Virginia, in 1908. This was close to Washington, D.C., where the Army's aviation group was based. However, the commander at Fort Myer didn't want the parade ground used for flight training anymore. The trials had messed up his summer training. Also, the Wright brothers didn't want to teach beginners in such a small space.

So, a new place was found near College Park, Maryland. It was about eight miles northeast of Washington, D.C. The Army's Signal Corps agreed to rent this spot. But the winter weather meant they couldn't train there all year. Because of this, they used different places in the south and west during the early 1910s. These included Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas, North Island in San Diego, California, and Augusta, Georgia.

However, Army flight training stayed small until the U.S. joined World War I in April 1917. In February 1913, the aviation school in Augusta, Georgia, moved to Texas City, Texas. This meant the main Army Aviation school was then at North Island, San Diego.

World War I Flight Training: A Big Boost

When the United States entered World War I, its allies, Britain and France, needed help fast. By 1917, fighting in the air was very important for winning battles on the ground. In May 1917, France asked the U.S. to send 5,000 pilots and planes. They also wanted 50,000 mechanics to help the French and British air forces.

The U.S. Army's training system was not ready for such a huge number of people. So, they decided to create a new system, much like Britain's. This system had three main parts: ground school, primary flight training, and specialized training. Pilots would learn to be pursuit (fighter) pilots, bombardment (bomber) pilots, or observation pilots.

Ground School: Learning Before Flying

The first step for new pilots was ground school. This was done first because many young men wanted to join the Air Service. Also, ground school didn't need planes or flight instructors. The Army sent people to Canada to learn how their ground schools worked.

The Canadian schools taught new classes every week, and students graduated in six weeks. After passing ground school, students went to flight school. This system helped find out early if students were not fit for flying. This saved time and resources. The U.S. decided to use the Canadian program but made it longer. It started at eight weeks, then went to ten, and finally to twelve weeks. They used American universities for this training.

During World War I, about 23,000 young men volunteered for flight training. Eight universities offered ground school training. These included:

- Princeton University, New Jersey

- University of Texas

- Cornell University, New York

- University of California

- University of Illinois

- Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Georgia School of Technology

- Ohio State University

After finishing ground school, cadets went to Camp John Dick Aviation Concentration Center in Dallas. This center was at the Texas State Fairgrounds. Here, cadets were organized into groups for their primary flight training.

Primary Flight Training: Getting Your Wings

When the U.S. joined World War I, the Army had fewer than 100 pilots. There were only three main flying fields: Hazelhurst Field in New York, Camp Kelly in Texas, and Rockwell Field in California. There was also a seaplane base in Pennsylvania, but it closed in 1917.

Building new training places in the U.S. would take a long time. So, Canada helped by letting American cadets train at bases near Toronto. The British Royal Flying Corps taught them. The British also ran three flying schools in the U.S. at Camp Taliaferro, Texas. This arrangement helped the U.S. learn about aerial gunnery (shooting from planes).

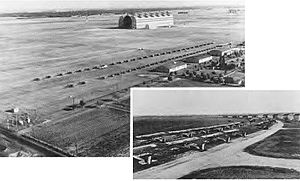

By late 1917, many new flying fields were built in the U.S. These included Wilbur Wright Field in Ohio, Chanute Field in Illinois, and Selfridge Field near Detroit. By October 1917, fourteen facilities were built, and nine had started flight training.

Many fields provided primary training in 1917. These included:

- Hazelhurst Field (New York)

- Selfridge Field (Michigan)

- Wilbur Wright Field (Ohio)

- Chanute Field (Illinois)

- Scott Field (Illinois)

- Camp Kelly (Texas)

- Rockwell Field (California)

On December 15, 1917, the five northern schools closed for winter. Cadets moved to the two southern schools for year-round training. Each training field had 100 airplanes and 144 cadets.

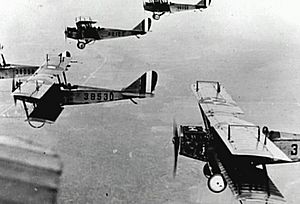

The main training plane was the Curtiss JN-4A Jenny. It was used throughout the war. Pilots needed six to eight weeks of training, with 40 to 50 hours of flying time, to earn their wings.

Advanced Training: Becoming a Specialist

More than 11,000 flying cadets earned their wings and became officers. Then they went through four weeks of advanced training. This training taught them to be specialists for different missions:

- Pursuit Pilots (Fighters): These pilots flew single-seat planes, usually high up. They learned how to fight enemy planes. Their training included studying plane parts, radio use, flying in formations, and combat moves.

- Observation Pilots (Scouts): These pilots flew with an observer. The observer gathered information and took photos of enemy positions. They learned how to spot enemy activities, take pictures, and use radios to talk to ground forces.

- Bombing Pilots (Bombers): These pilots and bombardiers flew planes across enemy lines, often at night. They learned about maps, compasses, and how to drop bombs. They practiced dropping both dummy and real bombs.

All combat pilots learned some aerial gunnery. Advanced gunnery training followed for pursuit pilots at their schools. Other pilots went to special aerial gunnery schools.

By May 1918, a bombing school was at Ellington Field in Houston. A pursuit school was at Gerstner Field in Louisiana. Observation schools were at Langley Field in Virginia and Post Field in Oklahoma. Gunnery schools were at Selfridge Field, Ellington Field, and Wilbur Wright Field.

Other special schools were also set up. Wilbur Wright Field taught armorers (people who worked with weapons). Brooks Field and Scott Field had schools for instructors. Radio training was taught at Carnegie Tech University and Columbia University. A photography school was developed at Langley Field.

The U.S. was in World War I for only about a year and a half. Because of this, only about 1,000 of the 11,000 pilots trained actually fought the enemy. Most of these pilots helped with artillery spotting or air-to-air combat. After the war, many flying schools closed. Some became local airports, while others stayed in service for many years.

World War I Flying Fields in the United States

Many airfields were used for training during World War I. Here are some of the main ones:

Aviation Section, U.S. Air Service Fields

|

First Reserve Wing Fields (Long Island, New York)

These fields focused on training squadrons for overseas duty and teamwork.

|

|

Second Reserve Wing Fields (Texas Area)

|

|

** Camp Taliaferro was a flight training center near Fort Worth, Texas. It had three main airfields: Hicks Field, Barron Field, and Carruthers Field. From 1917 to 1918, British Royal Flying Corps instructors trained 6,000 flight cadets there.

Balloon Observer Schools

These schools trained people to observe from balloons.

|

|

Other Training Airfields

|

|

Training in Europe: American Expeditionary Force

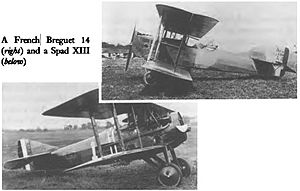

When American troops went to France, they got more training at special Air Instructional Centers (AICs). They used French and British planes, which were the same types used in combat. This extra training was needed because the U.S. didn't have enough equipment at home.

At first, the U.S. planned to do only advanced training in Europe. But because primary flight training wasn't fully set up in the U.S., American cadets were sent to French, British, and Italian schools. About 200 men went to England, and about 500 cadets went to Foggia, Italy, for primary training.

Most American cadets trained in France. The Third Aviation Instruction Center (3d AIC) at Issoudun Airdrome, France, was originally for advanced training. But it was also used for primary training. Other schools, like Tours Airdrome, were also used for primary training. The old French aero school at Tours became the 2d AIC in September. It stayed the main American primary flying school in France.

Tours and Issoudun trained as many cadets as possible. Some new arrivals stayed in barracks in Tours, St. Maixent, or Paris. In January 1918, all untrained cadets were sent to St. Maixent. This became the main gathering point for all aviation troops arriving in Europe.

The French used different planes for combat and training. Americans at Avord learned on planes like the Bleriot or Caudron. Promising cadets then moved to the Nieuport for advanced fighter training. The Caudron G-3, an older reconnaissance plane, was often used for primary training at Tours.

The Italians agreed to train up to 500 cadets at a school in Foggia, Italy. This school, the 8th AIC, started training the first group of cadets in September 1917. These cadets were top students from American ground schools.

- Aviation Instruction Centers (AICs) in Europe

|

|

- Artillery Aerial Observation Schools

These schools taught pilots and observers how to work with artillery on the ground.

|

|

After the War: Changes and Closures

In early 1919, the Air Service had big plans. They wanted to keep fifteen flying fields and five balloon schools for training. Some of these, like Rockwell, Langley, Post, and Kelly Field No. 1, were already owned by the government. They planned to open several primary schools and separate advanced training sites for bombing, observation, fighter, and gunnery pilots.

However, after World War I ended, the Army quickly reduced its size. Many of the leased wartime facilities were closed. By the end of 1919, most were no longer active airfields. Only a small group of people stayed to manage them.

Images for kids