United States nationality law facts for kids

United States nationality law explains how a person becomes a member of the United States. This usually happens because of rules in the U.S. Constitution, different laws, and international agreements. Being a citizen is a right. While the words "citizenship" and "nationality" are often used to mean the same thing, nationality is about how someone officially becomes part of a country. Citizenship is about the rights and duties of those members.

Most people born in any of the 50 U.S. states, Washington, D.C., or almost any inhabited U.S. territory are U.S. citizens from birth. The only main exception is American Samoa. People born there are usually U.S. nationals but not full citizens. People from other countries who live in a state or qualified territory can become citizens later. They must first become permanent residents and live in the U.S. for a certain time (usually five years).

Contents

History of U.S. Nationality

Early Rules and the Constitution

Nationality describes the legal connection between a person and a country. It shows who belongs to a nation. The rights and duties of citizens come from this connection. The Constitution of the United States didn't originally define nationality or citizenship. But in Article 1, Section 8, Clause 4, it gave Congress the power to create laws about becoming a citizen. Before the American Civil War and the Fourteenth Amendment, there wasn't much else in the Constitution about nationality.

Nationality Laws from 1790 to 1866

The first law about nationality in the U.S. was the Naturalization Act of 1790. It said that only free, white people could become nationals. Back then, women's loyalty was often seen as belonging to their husbands, not the country. So, even though the law didn't stop women from having their own nationality, court decisions often meant that women, children, and enslaved people couldn't take part in public life. This was because people believed they couldn't make good decisions or control their own property.

Native Americans were seen as belonging to other governments. Court cases like Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857) said they could only become citizens if they adopted white culture. From 1802, only fathers could pass on their nationality to their children. Later laws in 1804 and 1855 made a wife's nationality, and her children's, depend on her husband's. If an American woman married a foreign man, it was assumed she gave up her U.S. nationality. She could get it back if her marriage ended and she moved back to the U.S.

History of U.S. Territories

The Territorial Clause of the Constitution gave Congress the power to make rules for U.S. territories. Congress decided which territories would eventually become states and which would not. Because of this, Congress has decided when people in these territories could become nationals and what their status would be. Before 1898, people born in U.S. territories were treated as if they were born in the U.S. They often became citizens all at once when the territory was acquired.

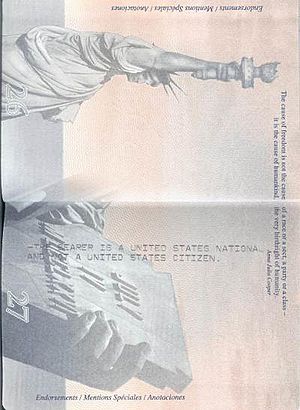

After 1898, some territories were treated differently. People in these "outlying possessions" were considered U.S. nationals but not full citizens. This included people in American Samoa, Guam, the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands. Non-citizen nationals don't have all the same rights as citizens, but they can live in the U.S. without a visa. Also, territorial citizens can't fully participate in national politics.

Over time, the U.S. gave citizenship to people in some of these territories.

- In 1900, people in Puerto Rico became citizens of Puerto Rico and U.S. nationals.

- In 1917, the Jones–Shafroth Act gave full citizenship rights to all people in Puerto Rico.

- In 1927, U.S. nationals in the U.S. Virgin Islands also gained citizenship rights.

- American Samoa became a U.S. territory in 1929. People there became non-citizen nationals.

- The Philippine Independence Act in 1946 meant Filipinos no longer had U.S. nationality.

- In 1950, people in Guam gained citizenship rights.

- In 1976, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands became a territory, and its people gained U.S. nationality with citizen rights.

How to Become a U.S. National Today

There are several ways to become a U.S. national. This can happen at birth, through a process called naturalization, or sometimes through court decisions or treaties.

Born in the United States

The Fourteenth Amendment says that "All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States." This means that if you are born in the U.S., you are usually a citizen. This is true even if your parents are not citizens, unless they work for a foreign government. A birth certificate from the U.S. is usually proof of nationality.

Born Abroad to U.S. Citizens

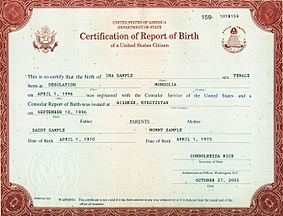

If a child is born outside the U.S. to U.S. citizen parents, they can also become a national. A "Consular Report of Birth Abroad" can confirm this.

- If both parents are U.S. nationals, the child automatically gets nationality if one parent lived in the U.S. or its territories at some point.

- If one parent is a U.S. citizen and the other is not, the U.S. citizen parent usually needs to have lived in the U.S. or its territories for a certain amount of time before the child was born. This time varies depending on when the child was born.

For children born to unmarried parents, the rules used to be different for mothers and fathers. But in 2017, the Supreme Court ruled that the rules must be the same for both parents.

Adoptions

Before 2000, adopted children from other countries had to go through a separate naturalization process. But with the Child Citizenship Act of 2000, things changed. Now, if U.S. citizens adopt a child from another country, and the child is under 18 and legally brought to the U.S., they automatically become a U.S. national once the adoption is final.

Born in U.S. Territories

For people born in U.S. territories, their nationality depends on when they were born. Congress has passed laws to give nationality to people born in most inhabited territories, like Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, Guam, and the Northern Mariana Islands.

However, people born in American Samoa and Swains Island are usually U.S. non-citizen nationals. This means they are part of the U.S. but don't have all the same rights as citizens. There have been court cases about this, but for now, this special status remains.

Naturalization Process

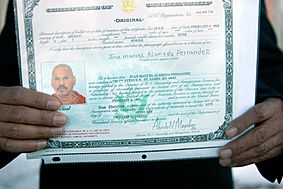

If a person was not born a U.S. national, they can become one through a process called naturalization.

Who Can Apply for Naturalization

To become a naturalized citizen, a person must be at least 18 years old. They must be a legal permanent resident of the U.S. and have had this status for five years before applying. They also need to have been physically present in the U.S. for at least two and a half years. If someone is married to a U.S. national and lives with them, the waiting period can be shorter (three years).

Some people have special rules. For example, immigrants who served honorably in the U.S. military during wartime might not need to be permanent residents first. Also, people who have made amazing contributions, like scientists or Olympic athletes, might have fewer requirements.

Children adopted by U.S. citizens who didn't get nationality at birth can also qualify for special naturalization.

Steps to Naturalization

Applicants must apply with the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services and pay fees. They need to show they are of good moral character, meaning they don't have a criminal history. They must also pass a test on U.S. history and civics. The questions for this test are available online. Most applicants also need to show they can read and write basic English. However, some long-term permanent residents are exempt from the language test. For example, older applicants with many years of residency can take the civics test in their own language.

Finally, to become a citizen, applicants must take an Oath of Allegiance. There are exceptions for people with certain physical or mental disabilities.

Losing U.S. Nationality

It is very difficult to lose U.S. nationality against your will. In the past, it was easier to lose nationality for things like living abroad for too long or marrying a foreign person. However, court decisions have made it clear that a person must truly intend to give up their nationality for it to be lost.

Since 1990, the U.S. government generally assumes that a person does not intend to give up their nationality, even if they do things like become a citizen of another country. This means that people can often have multiple nationalities.

Nationality can still be lost in certain situations:

- Treason or conspiring against the U.S.

- Working as a high-level official for a foreign government.

- Voluntarily giving it up (renunciation).

- If it was obtained by fraud (for example, if someone lied on their naturalization application). This is called denaturalization.

The process of denaturalization is a legal one. It requires clear proof that nationality was obtained by fraud.

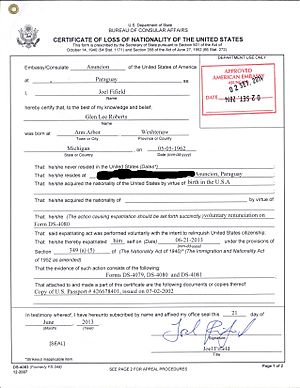

Renouncing nationality means you formally and willingly give up your U.S. national identity and all its rights. This is done by making a formal statement to a U.S. official, usually at an embassy or consulate abroad. You will have an interview and sign papers to show you understand what you are doing.

People who give up U.S. nationality might have to pay an expatriation tax. This tax is meant to prevent people from giving up their nationality just to avoid U.S. taxes.

Having Dual Nationality

The U.S. Supreme Court has said that having dual nationality (being a citizen of two countries) is a recognized status. This means a person can have rights and responsibilities in two countries. The U.S. government allows people to have multiple nationalities, even though it doesn't officially encourage it.

However, having dual nationality can sometimes affect things like getting a security clearance or access to classified information for government jobs.

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |