Upheaval of the Five Barbarians facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Upheaval of the Five Barbarians (五胡亂華) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

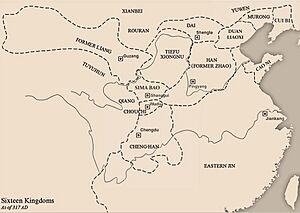

How the Five Barbarians moved into China before the big changes. |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Han-Zhao |

Xianbei allies Tuoba in Dai Duan tribe in Liaoxi |

Cheng-Han | Sima Ying loyalists (307–308) | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Liu Yuan Liu Xuan Liu Cong Liu Yao Shi Le (after 307) Wang Mi |

Emperor Huai of Jin Emperor Min of Jin Sima Yue Gou Xi Wang Yan Liu Kun Wang Jun Sima Bao Zhang Gui Zhang Shi Tuoba Yilu † Duan Wuwuchen Duan Jilujuan Duan Pidi Luo Shang |

Li Xiong Fan Changsheng |

Ji Sang † Shi Le (before 307) |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| c. 100,000 Xiongnu, Jie, Di, Qiang, Xianbei, Han Chinese and other tribal people | 100,000–200,000 Han Chinese, Xianbei, Qiang, Di and Wuhuan | Ba-Di rebels and Han Chinese allies | Han Chinese and non-Han rebels | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

| Upheaval of the Five Barbarians | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 五胡亂華 | ||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 五胡乱华 | ||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Five Barbarians disorderize China | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

The Upheaval of the Five Barbarians (also called the Uprising or Rebellion of the Five Barbarians) was a very messy time of wars in China. It happened during the Jin dynasty (266–420) from about 304 to 316 AD. Many non-Han groups living in China, known as the Five Barbarians, were involved. This period happened at the same time as the War of the Eight Princes, which made the Jin empire very weak. These conflicts eventually forced the Jin government to leave northern and southwestern China.

The "Five Barbarians" were the Xiongnu, Jie, Qiang, Di, and Xianbei. Many of them had moved into China over the past few centuries. Even though the period is named after them, many Han Chinese and other tribal groups like the Wuhuan also joined the rebellions. Years of bad leadership and civil wars between the ruling princes made the empire easy for unhappy or ambitious groups to attack.

Tensions between the Han people and the tribes, especially the Qiang and Di, in the Guanzhong region led to big revolts. This caused many people to flee to southwestern China. When the government tried to force them back, they fought back. This led to the rebellion of Li Te, a Ba-Di refugee, in 301 AD.

In the north, the Southern Xiongnu in Shanxi used the Jin princes' fighting to start their own state called Han-Zhao in 304 AD. They chose Liu Yuan as their leader. As revolts against Jin spread, a former Jie slave named Shi Le became very powerful. After joining Liu Yuan, he controlled the eastern part of the new empire.

In 311 AD, Han forces captured Emperor Huai of Jin and the old capital, Luoyang. This event is known as the Disaster of Yongjia. In 316 AD, Jin's hope of getting back control in the north was crushed when Han defeated and captured Emperor Min in Chang'an. The start of Cheng-Han and Han-Zhao in 304 AD is seen as the beginning of the Sixteen Kingdoms period. After Emperor Min's defeat, the Eastern Jin dynasty was formed by Emperor Yuan in Jiankang in 318 AD. For about 130 years, China was divided between the Sixteen Kingdoms in the north and the Eastern Jin in the south.

Contents

Why the Upheaval Started

Weakening of the Jin Dynasty

When the Jin dynasty began in 266 AD, Emperor Wu of Jin wanted to avoid the mistakes of earlier rulers. He gave power to the princes, letting them become military governors with their own armies. But after he united China in 280 AD, Emperor Wu reduced the army's size everywhere. He hoped this would stop powerful families from taking over.

However, these choices led to the War of the Eight Princes after his death in 290 AD. His successor, Emperor Hui of Jin, had a developmental disability. So, the princes fought each other for control of the empire.

While the Jin army became weaker from these internal fights, many undefended areas became easy targets for unhappy or ambitious people. In the last years of the Western Jin, tribal groups known as the Five Barbarians became very powerful in northern and western China. These groups were the Xiongnu, Jie, Qiang, Di, and Xianbei.

Tribal Groups in China

Nomadic people had been moving into China for a long time, even before the Han dynasty. For example, the Southern Xiongnu became allies of the Han in 50 AD. They moved their court inside the Great Wall and traded with the Han. Even after the Han dynasty ended, they remained allies.

Over time, some Xiongnu leaders felt unhappy with their new way of life. They felt their old titles were meaningless and they had lost land. Revolts happened in 272 and 294 AD, but they were quickly stopped.

Another group in the north was the Jie. Their exact origins are still debated, but they lived near the Xiongnu. Around 303-304 AD, a famine hit the north, forcing many Xiongnu, Jie, and other tribal people to move. The local governor captured and sold many of them into slavery to pay for his army during a civil war.

Tensions in Western China

In western China, the Qiang people and Di people had also moved into the Guanzhong region. They farmed and lived alongside Chinese settlers. However, they often faced unfair treatment from local officials, which led to big rebellions.

The end of the Han dynasty and the Three Kingdoms period encouraged more nomadic people to move in. They helped repopulate areas destroyed by war and provided workers and soldiers. The Guanzhong region became a battleground for warlords. In 219 AD, Cao Cao moved about 50,000 Di people to new areas. The Qiang and Di made up about half the population in Guanzhong.

Under the Western Jin, the northwest became chaotic because governors couldn't keep the tribes happy. From 296 to 299 AD, various tribes rebelled again, choosing the Di leader Qi Wannian as their "emperor." These rebellions, along with famines and diseases, devastated Guanzhong. Tens of thousands of refugees moved to Sichuan looking for food.

Some Jin officials worried about these rebellions. They suggested moving the tribal peoples out of China's borders, but these ideas were not accepted.

Alliances with Xianbei Tribes

After the Xianbei confederation broke up, the Murong, Duan, and Yuwen tribes moved to the Liaoxi region. They allied with Chinese dynasties, helping the Cao Wei and later the Jin. Another Xianbei tribe, the Tuoba, also became allies of Wei and Jin.

Around 300 AD, a Jin governor named Wang Jun allied with the Duan and Yuwen tribes. They helped him fight in the War of the Eight Princes. The Xianbei were key to winning the civil war, but they also helped attack cities like Ye and Chang'an, killing thousands. This showed Jin that these tribal allies were powerful, so they kept using them against the growing threat of Han-Zhao.

Climate Changes Affect China

Historians believe that changes in the weather also played a big part. The climate became colder and drier in the north, making it hard to farm. This led Chinese farmers to move south to warmer lands. At the same time, steppe peoples moved into northern China looking for fertile land.

The population of China dropped a lot. In 157 AD, the Han census counted 56.5 million people. By 280 AD, the Jin census counted only 16 million. Cold weather and dry lands caused natural disasters and famines, made worse by the War of the Eight Princes.

Rise of Cheng-Han

Refugees in Ba-Shu

The people who fled Qi Wannian's rebellion came from six areas in Guanzhong. They were both Han Chinese and tribal peoples. They first moved south to Hanzhong. One Di leader, Yang Maosou, took his followers to Chouchi and declared his group partly independent in 296 AD. Later, the Jin court allowed refugees to go further south into the Ba-Shu region (modern Sichuan). They spread out and worked for local people.

Among these refugees was a leader named Li Te. He and his family were Ba-Di people. In 300 AD, Li Te and his brothers joined a rebellion against Jin. They later took over Chengdu, the provincial capital. Li Te then submitted to Jin again but kept a lot of power as a representative for the refugee families.

Li Te's Rebellion and Cheng-Han's Start

In 301 AD, the Jin government ordered the refugees to return to Guanzhong. But the refugees didn't want to go because they thought it was still dangerous and they didn't have enough supplies. Li Te tried to delay their return. But the Jin governor, Luo Shang, got tired of waiting and tried to force them to move. Many refugees gathered around Li Te to defend themselves. In the winter of 301 AD, Luo Shang attacked them, starting a three-year rebellion led by Li Te.

Li Te won many battles against the Jin forces. In 303 AD, his forces reached Chengdu. He declared a new era, suggesting he was starting a new government. But he was suddenly killed in an ambush. His brother, Li Liu, took over, and after he died, Li Te's son, Li Xiong, became the leader. In 304 AD, Li Xiong drove Luo Shang out of Chengdu and started the state of Cheng (later renamed Han, so it's called Cheng-Han).

Li Xiong first called himself King, then Emperor in 306 AD. Cheng-Han grew slowly, mostly by taking over areas where other refugee revolts happened. Their biggest gain was in 314 AD when rebels in Hanzhong gave the region to Cheng.

Rise of Han-Zhao

Founding of Han-Zhao

In 304 AD, the Xiongnu nobles in Bing province decided to use the Jin princes' fighting to break away from the empire. Liu Yuan, a Xiongnu general, was serving a Jin prince. Liu Yuan was popular among both Xiongnu and Han Chinese people.

Liu Yuan's granduncle convinced the Xiongnu to choose Liu Yuan as their leader. Liu Yuan was given permission by the Jin prince he served to return to Bing to gather Xiongnu soldiers. Once he arrived, he was declared the new Grand Chanyu and quickly gathered about 50,000 soldiers.

Later in 304 AD, Liu Yuan started the state of Han (later renamed Zhao, so it's called Han-Zhao). Even though he was Xiongnu, Liu Yuan said his state was a continuation of the Han dynasty. He first took the title of King, then Emperor in 308 AD. He welcomed Han Chinese and other non-Xiongnu tribes like the Xianbei and Di to join his forces.

Rebellions in the Northeast

In the next few years, more rebellions started in northeastern China. Many of these rebel leaders were Han Chinese. But the most important one was Shi Le, a Jie chief who had been sold into slavery during the famine in Bing province.

After one rebellion was defeated, Shi Le gathered followers in Shandong. They raided areas and grew their forces. In 307 AD, they attacked and burned the city of Ye for ten days, killing about 10,000 people. Shi Le survived later defeats and joined Han-Zhao.

Another rebel leader, Wang Mi, also survived a defeat and formed a large bandit group in Shandong. In 307 AD, he attacked several provinces, killing many officials. Wang Mi then joined Han-Zhao. By 308 AD, his forces were huge, and he even tried to attack Luoyang, the Jin capital, but failed. Wang Mi then brought his forces to Han-Zhao.

Under Liu Yuan, Shi Le and Wang Mi became powerful commanders. Shi Le was given full command over the armies east of the Taihang Mountains.

The Disaster of Yongjia

By 307 AD, the War of the Eight Princes had ended, but the Jin dynasty was in a tough spot. The civil wars had weakened the Jin army in the north, leaving major cities like Luoyang vulnerable. Famine also got worse due to natural disasters. In 309 AD, a great drought made rivers so low you could walk across them. The next year, locust swarms hit six northern provinces.

The wars and famines led to groups of refugees forming, some fleeing south, others defending themselves in fortresses. The Book of Jin described the famine as terrible, with people being sold as slaves, widespread disease, and even cannibalism.

In 308 AD, Han-Zhao conquered Pingyang, moving their capital closer to Luoyang. Liu Yuan's son, Liu Cong, attacked Luoyang twice in 309 AD but failed. The Jin leader, Sima Yue, left Luoyang with the imperial army in 310 AD to fight Shi Le, leaving the emperor behind.

After Liu Yuan died in late 310 AD, his successor was quickly overthrown by Liu Cong. Liu Cong then tried to capture Luoyang again. In 311 AD, Sima Yue died from stress. His army, on its way to his funeral, was attacked and defeated by Shi Le at the Battle of Ningping. More than 100,000 soldiers died.

This defeat left Luoyang undefended. In July 311 AD, the Han armies entered the city, massacring people and burning it down. More than 30,000 people died. This event is known as the Disaster of Yongjia. Emperor Huai was captured and later killed. Just a few months later, Han forces also captured Chang'an.

Final Defeat of Western Jin

Restoring Chang'an

Even after losing their emperor and capital, the Western Jin dynasty lasted another five years. In 312 AD, some Jin generals managed to take back Chang'an. They then declared the 12-year-old Emperor Min of Jin (Emperor Huai's nephew) as the new emperor in 313 AD. Other Jin governors also kept fighting Han-Zhao.

Emperor Min was very young, so his generals mostly controlled things. These generals soon fought each other, and Emperor Min ended up under the control of Suo Chen and Qu Yun. Their power was limited to Chang'an and its nearby areas. Jin officials in Guanzhong were not eager to help the new government. Emperor Min had to rely on governors from western provinces for help.

Many Qiang, Di, and other tribes in the region were left to themselves. Some sided with Han-Zhao, some stayed loyal to Jin, and others remained neutral, forming their own independent areas.

Shi Le's Conquests

Shi Le became very powerful in the northeast. After the Disaster of Yongjia, he killed Wang Mi and took over his army. Liu Cong, the Han-Zhao emperor, was afraid Shi Le would rebel, so he couldn't punish him. Shi Le controlled Han-Zhao's eastern lands.

The strongest Jin forces in the northeast were led by Wang Jun and Liu Kun, who were supported by the Xianbei Duan and Tuoba tribes. The Duan helped Wang Jun stop Shi Le's forces. The Tuoba formally allied with Liu Kun in 309 AD.

However, both Wang Jun and Liu Kun depended heavily on their tribal allies. They had trouble keeping people in their territories, as many refugees left to join the safer Xianbei areas. Wang Jun and Liu Kun also didn't trust each other and refused to work together.

Shi Le used these weaknesses. He captured a cousin of the Duan chief, which led to talks between them. The Duan agreed to cut ties with Wang Jun. The Wuhuan tribes also joined Han-Zhao. Without his tribal forces, Shi Le captured Wang Jun in 314 AD and executed him. In 316 AD, the Tuoba fell into civil war, leaving Liu Kun without his main ally. Liu Kun was defeated, and his province surrendered to Han-Zhao.

Fall of Chang'an

Liu Yao, a Han-Zhao general, was tasked with taking back Chang'an. After Emperor Min became emperor in 313 AD, Liu Yao and other Han generals immediately attacked. Emperor Min's generals won some battles but couldn't stop the Han advances. In the autumn of 316 AD, Liu Yao finally surrounded Chang'an.

The city's defenders fought hard, but by winter, they ran out of food. Most people had either fled or died. With no help coming, Emperor Min surrendered to Han-Zhao on December 11, 316 AD.

What Happened Next

The Sixteen Kingdoms Period

Even though Han-Zhao had military success, it was unstable inside. The emperor, Liu Cong, fought with his own officials and executed many important people. After he died in 318 AD, his successor and family were killed in a coup. Liu Yao and Shi Le teamed up to defeat the coup leader. Liu Yao became the new emperor. However, Shi Le declared his independence in 319 AD. Liu Yao moved the capital to Chang'an and renamed his state (Former) Zhao. Shi Le started his own state, (Later) Zhao. This led to a ten-year war that ended with Han-Zhao's defeat and Later Zhao controlling most of northern China.

The start of Han-Zhao and Cheng-Han in 304 AD is often seen as the beginning of the Sixteen Kingdoms period. As Jin lost control in the north, other groups like the Zhang clan in Liang province and the Murong tribe in Liaodong became independent. Their strong defenses and good leadership made them popular places for refugees. The Zhang clan's government is known as the Former Liang. The Murong founded the Former Yan in 338 AD. Over time, more of the Sixteen Kingdoms appeared.

The Eastern Jin Dynasty

Liu Cong had Emperor Huai and Emperor Min killed in 313 and 318 AD. Both emperors were forced to serve as Liu Cong's servants before being executed. After Emperor Min's death, Sima Bao tried to claim the throne but died before he could. His forces were crushed by Liu Yao. In Hebei, some Jin resistance remained after Wang Jun and Liu Kun's defeats, but by 321 AD, they were all defeated by Later Zhao.

In southern China, the Jin court had moved to Jianye (later Jiankang). With the help of cousins Wang Dun and Wang Dao, Sima Rui gained the support of powerful families there.

As the upheaval happened, Jiankang became a center of power in southern China. Many northern officials fled south to serve Sima Rui. After Emperor Min was captured, the powerful families supported Sima Rui to become emperor. The Jiankang government wasn't very interested in helping Emperor Min take back northern China. When a general named Zu Ti offered to lead an expedition north, Sima Rui allowed it but gave him very few supplies or soldiers. With Emperor Min's death in 318 AD, Sima Rui declared himself emperor and founded the Eastern Jin dynasty, officially moving the Jin court to the south.

Long-Term Effects

The fall of the Western Jin had huge, lasting effects. Just 24 years after the Western Jin dynasty ended the Three Kingdoms period in 280 AD, China was divided again. The Sixteen Kingdoms period brought constant warfare and economic problems to northern China. This period ended in 439 AD when the north was united by the Northern Wei. China wouldn't be fully united again until the Sui dynasty in 589 AD.

This era was a time of military disaster, but also a time when different cultures mixed. The tribal groups brought new ways of governing and encouraged new religions like Buddhism. Also, many educated Jin leaders moved south. They spread Chinese culture to areas south of the Yangtze River, like modern-day Fujian and Guangdong.

Han Chinese Migrations

The chaos in the north caused many Han Chinese people to move south of the Huai River, where things were more stable. This move of Jin nobles south is called yī guān nán dù (meaning "garments and headdresses moving south"). Many who fled were from important families, like the Xie and Wang clans. Wang Dao was especially important in helping Sima Rui start the Eastern Jin dynasty. The Eastern Jin relied on both southern nobles and northern nobles who had fled. It became a weaker dynasty, controlled by regional nobles, but it lasted for another century in the south.

The "Eight Great Surnames" were eight noble families who moved from northern China to Fujian in southern China because of the upheaval. These surnames were Hu, He, Qiu, Dan, Zheng, Huang, Chen, and Lin.

Mass migrations led to the growth of southern China's population, economy, farming, and culture, as it remained peaceful. The Eastern Jin government used "yellow registers" to count the original southern Han Chinese population and "white registers" for the huge number of northern Han Chinese migrants.

Later, after the Northern Wei brought stability to northern China, some people even moved back north. Han Chinese nobles from the southern dynasties who fled north often married princesses from the Northern Wei's Xianbei Tuoba tribe.

Han Chinese refugees from the upheaval also moved to the Korean peninsula and into the Murong Former Yan state. The Eastern Jin kept some influence over the Murong state for a while. Han Chinese refugees also moved west into the Han Chinese-controlled Former Liang.

The descendants of northern Han Chinese aristocrats who fled south and the local southern Han Chinese aristocrats combined to form the Chinese Southern aristocracy during the Tang dynasty. They saw themselves as preserving Han culture and mostly married only within their own group.

Southern Chinese Daoism developed from a mix of the religious beliefs of these local southern Han Chinese aristocrats and the northern Han Chinese who fled south.

|

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |