Utricularia resupinata facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Utricularia resupinata |

|

|---|---|

|

|

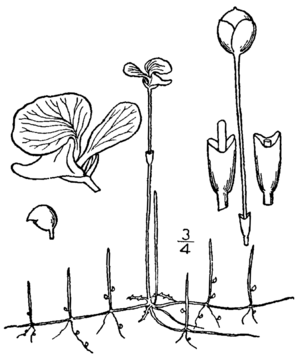

| 1913 botanical illustration. | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Asterids |

| Order: | Lamiales |

| Family: | Lentibulariaceae |

| Genus: | Utricularia |

| Subgenus: | Utricularia subg. Utricularia |

| Section: | Utricularia sect. Lecticula |

| Species: |

U. resupinata

|

| Binomial name | |

| Utricularia resupinata Greene ex Bigelow

|

|

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

|

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

Utricularia resupinata, also known as lavender bladderwort or northeastern bladderwort, is a small perennial plant. This means it lives for more than two years. It grows partly underwater and is a carnivorous plant, meaning it eats tiny animals. It belongs to the Utricularia genus in the Lentibulariaceae family. You can find it in eastern Canada, the United States, and Central America. This plant has an interesting history, how it grows, and how it fits into nature. It is also a plant that needs protection in many places where it lives.

Contents

- What is the Lavender Bladderwort?

- How does the Lavender Bladderwort look?

- Where does the Lavender Bladderwort grow?

- Where can you find the Lavender Bladderwort?

- How is the Lavender Bladderwort classified?

- Who studied the Lavender Bladderwort?

- Why is the Lavender Bladderwort in danger?

- Images for kids

- See also

What is the Lavender Bladderwort?

When scientists write about this plant, they often call it "Utricularia resupinata B. D. Greene ex Bigelow." This is its scientific name. Utricularia is the genus, and resupinata is the specific name for this plant. The names "Benjamin Daniel Greene" and "Jacob Bigelow" tell us who first found and wrote about the plant.

In botany, plants get two names, like a first and last name. This is called binomial nomenclature. Scientists cannot name a plant after themselves. They might name it after the person who found it, a place, or a special feature of the plant.

The name Utricularia resupinata comes from two Latin words. Utriculus means "a small bottle." This refers to the plant's bladders, which trap insects. Resupinata means "bent or thrown back." This describes the top part of the bladderwort's flower.

How does the Lavender Bladderwort look?

An old drawing from 1913 shows this bladderwort. It has a thin stem, about 2 to 12 inches long. This stem grows along or just under the water's surface. Its roots are slender and often hidden in sand or mud. The leaves are very tiny or sometimes not there at all.

The plant has pretty blue to purple flowers. They bloom from August to September. Each flower has two parts, like lips. The top part faces up. The bottom part has three lobes and a small sac at its base.

After flowering, the plant forms fruit in a small sac with two parts. This sac holds tiny seeds. It grows on a separate stem. The fruit dries out and opens when it's ready.

The bladderwort can make new plants in two ways. It can grow from seeds. It can also make special buds called turions. These buds break off and grow into new plants nearby.

This plant is a carnivorous plant. It catches and eats tiny animals. This is why it's in the Lentibulariaceae family. A typical plant has about 12 to 100 bladders. These bladders are 1 to 6 millimeters big. They act as "traps" for small creatures. The lavender flower with its projecting sac is a good example of this plant's unique look.

Where does the Lavender Bladderwort grow?

Utricularia resupinata likes to grow at the edges of wet areas. You can find it along the shores of ponds, lakes, or rivers. It also grows in moist, sandy soil, sometimes even near new roads. It prefers sandy ground covered with a thin layer of mud.

In colder areas, it seems to flower only when the water levels are low and the temperatures are warmer than usual. This plant was once thought to be completely gone from Indiana. But it was found again in 2005!

A specific plant specimen was collected in May 1961. It was found by George R. Cooley and others on the shore of Lake Tsala Apopka, Florida. It was growing in about half an inch of water. This specimen is now at the University of South Florida herbarium. It shows the plant with flowers, many stems, tiny leaves, bladders, and seeds.

Where can you find the Lavender Bladderwort?

In 1848, Professor Asa Gray wrote about Utricularia resupinata. He said it was found only in a small area, from eastern Maine to Rhode Island. But soon, people found it in new places.

In 1879, a member of the Syracuse Botanical Club found it in northern New York. This was reported in the "Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Society".

Frank Tweedy was a plant collector. He had been working in New York since 1876. He found Utricularia resupinata in several more spots in the Adirondack Mountains. He wrote:

I collected that plant in August, 1875, at the same locality…namely, muddy shore of Beaver Lake, No. 4, Lewis Co., N.Y. During the past season I collected quite a number of the same plant on the shore of Big Moose Lake, Herkimer Co., N.Y., and at Twitchell Lake, in the same county. I do not think it is uncommon through Northern New York.

Since then, Utricularia resupinata has been found in Canada, the eastern US (including the Great Lakes states), and Central America. A map by "The Floristic Synthesis of North America (BONAP)" shows its wider range. However, it is becoming rare or endangered in many states.

How is the Lavender Bladderwort classified?

Scientists put living things into groups. This is called taxonomy or scientific classification. At the very top is the kingdom of plants, called Plantae.

Plants are then grouped into smaller categories:

- Tracheophytes: Plants with tubes to carry water.

- Angiosperms: Plants that produce flowers.

- Eudicots: Flowering plants that start with two seed leaves.

- Asterids: A large group of flowering plants.

- Lamiales: An order of flowering plants with certain features, like opposite leaves. This group is huge, with over 23,000 species!

Utricularia resupinata fits into all these groups. Its family (biology) is Lentibulariaceae, which includes all carnivorous plants. This family has three main groups, or genera: corkscrew plants (Genlisea), butterworts (Pinguicula), and bladderworts (Utricularia).

Within the Utricularia genus, there are about 240 species. Utricularia resupinata is one of them. Sometimes, plants get new names. These old names are called "synonyms." For example, Lecticular resupinata and Utricularia greenei were once names for Utricularia resupinata. The name Lecticular means "couch" because of a special part on the plant's lower stem.

The Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (APG) is a group of botanists. They work to create a standard way to classify all flowering plants. This helps scientists around the world use the same names. The classification here is based on their latest work.

Who studied the Lavender Bladderwort?

Discovery

The scientific name "Utricularia resupinata B.D. Greene ex Bigelow" tells us about its discovery. Benjamin Daniel Greene (1793–1862), a lawyer from Massachusetts, found this flowering plant. His discovery was reported in a book by Jacob Bigelow (1787–1879). Bigelow was an American botanist and doctor. He wrote about plants in the Boston area.

Specimens in herbaria collections

A herbarium is like a library for plants. It's a collection of dried and preserved plant specimens used for scientific study. Two of Frank Tweedy’s bladderwort finds are in herbaria today. One is at Harvard University, and the other is at the University of Vermont. Both were collected in 1879.

Many specimens of this species are in herbaria. The oldest one is B.D. Greene’s specimen from 1829. It is now at the New York Botanical Garden. The most recent one was found in 2019 in South Carolina.

Early plant bladder study

Mary Treat (1830-1923) was a naturalist who studied Utricularia resupinata. She spent many hours looking at the bladders under her microscope. She wanted to know how these "little bladders" trapped and ate tiny animals.

People first thought the bladders helped the plant float. But Mary Treat was one of the first scientists to think they were actually traps. She wrote a whole chapter about the Utricularia genus in her book Through a Microscope. She was amazed by how the bladders worked:

I have found almost every swimming animalculæ with which I am acquainted, caught in these vegetable traps; and when caught they never escape. Their entrance is easy enough; there is a sensitive valve at the mouth of the bladder, which, if they touch it, flies open and draws them in as quick as a flash. These downward-opening bladders not only entrap animalculæ, but, more wonderful still, the strong larvæ of insects.

Correspondence between Charles Darwin and Mary Treat

Mary Treat also wrote letters to the famous biologist Charles Darwin for five years. Darwin was studying carnivorous plants. They debated how insects entered the bladders. Mary eventually convinced him of her idea. She shared this story in her book:

Those who have read Mr. Darwin’s very interesting book on Insectivorous Plants, will have noticed that he says the valve of Utricularia is not in the least sensitive, and that the little creatures force their way into the bladders -- their heads acting like a wedge. But this is not the case, as Mr. Darwin himself was convinced some years before his death. In his usual kind, gracious manner he admitted that he was wrong, and gracefully says the valve must be sensitive, although he could never excite any movement. In a letter to me bearing date June 1st, 1875, he says: "I have read your article (in Harper’s Magazine) with the greatest interest. It certainly appears from your excellent observations that the valve is sensitive...I cannot understand why I could never with all my pains excite any movement. It is pretty clear I am quite wrong about the head acting like a wedge. The indraught of the living larva is astonishing.”

A name change

As botany science grew, Utricularia resupinata was moved to a new group. In 1913, John Hendley Barnhart (1871-1949) from the New York Botanical Garden put it into a section called "Lecticula." He did this because of its unusual stem parts. The two species in this group have unique bracts, which are small leaf-like structures.

Later, botanist Norman Taylor wrote about this new category in 1915. He listed Utricularia resupinata under its new name, Lecticula resupinata. This name is now considered a synonym for Utricularia resupinata.

Systematic study of the Utricularia genus

Peter Geoffrey Taylor (1926-2011) spent 41 years studying the Utricularia genus. In 1989, he published a big book called The Genus Utricularia: A Taxonomic Monograph. In this book, Utricularia resupinata was one of the 240 species. It was also put back under its original name. Taylor's book was very important because it studied an entire genus in great detail.

Continuing interest in the plant bladder

Mary Treat saw how the tiny bladders of Utricularia trapped small animals. When a mosquito larva touched sensitive hairs, the bladder snapped shut. But one thing puzzled her: "I soon became satisfied that the valve was very sensitive when touched at the right point, but to this day I cannot tell what the power is that so quickly draws the creatures within."

Recent research has answered some questions and brought up new ones. The Utricularia traps are the smallest among carnivorous plants. But they are also thought to be the most complex and amazing.

Three observations from recent research

Lubomir Adamec, a botanist from the Czech Republic, has looked at a lot of recent research on Utricularia bladders. Here are three interesting things they found:

- Energy use: This plant uses a lot of energy for its bladders. When a small animal touches hairs on the trap door, it opens. The animal is sucked in, and the door closes very quickly. This happens in about 10 to 15 milliseconds! It's the fastest plant movement known. Scientists are still studying where this energy comes from.

- Bladder soup: Not all the tiny animals sucked into the traps are digested. Some organisms inside the bladder actually help break down the prey. This is like what happens in a good septic system. These tiny living things, like bacteria and protozoa, live with the plant in a helpful way. This "miniature food web" offers many possibilities for future study.

- Oxygen levels: The amount of oxygen inside the bladder is very important. Captured organisms either die from lack of oxygen and become food, or they can survive without oxygen and live with the plant. Utricularia traps likely kill their prey by making them suffocate.

Lubomir Adamec's research shows how complex this plant's bladder is. It involves mechanics, like water pumping in and out very fast. It also involves electro-chemistry, with voltage transfers. And it shows how tiny animal species live together inside this plant bladder, either helping or becoming food.

Why is the Lavender Bladderwort in danger?

There are big worries about Utricularia resupinata in many places. The US Department of Agriculture lists its status:

- Of Special Concern: Rhode Island and Tennessee.

- Threatened: Massachusetts and Vermont.

- Endangered: Connecticut, Maine, Maryland, and New Jersey.

- Extirpated (meaning it was thought to be gone): Indiana and Pennsylvania. (Though it was recently found again in Indiana!)

Three main reasons are given for why this plant is in danger:

- Heavy use of waterways: Too many boats or people in the water can harm its habitat.

- High nutrient levels: Fertilizers from lawns or bad septic systems can pollute the water.

- Competition from other plants: Both native and invasive species can outcompete the bladderwort.

A plan is needed to protect and help this special plant grow. It fascinated scientists like Frank Tweedy, Mary Treat, and Charles Darwin. It's important to keep it safe for future generations.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Utricularia resupinata para niños

In Spanish: Utricularia resupinata para niños

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |