Angiosperm Phylogeny Group facts for kids

The Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (often called APG) is a group of plant scientists from around the world. They work together to create a shared way of classifying flowering plants. This classification uses new information about how plants are related. This information comes from studying their DNA and family trees.

Since 1998, the APG has published four main versions of their classification system. These came out in 1998, 2003, 2009, and 2016. A big reason for this group was that older ways of classifying plants were not based on "monophyletic" groups. This means the old groups did not include all the descendants from a single common ancestor.

The APG's ideas are now very important. Many large plant collections, like those in Kew Gardens, are now arranged using the latest APG system.

Contents

How APG Classifies Flowering Plants

In the past, one scientist or a small team usually created plant classification systems. This led to many different systems around the world. For example, the Engler system was popular in Europe. The Bentham & Hooker system was used in Britain. The Cronquist system was common in the United States.

Before scientists could study plant DNA, they classified angiosperms (flowering plants) based on their shape (especially their flowers) and biochemistry (the chemicals inside them).

After the 1980s, new ways to study plant DNA became available. Scientists could now use phylogenetic methods to analyze this genetic evidence. This new information confirmed some old ideas but completely changed others. This led to many new ideas for how to classify plants. It made things a bit confusing for a while!

A big study in 1993 looked at the DNA of 5,000 flowering plants. It focused on a gene involved in photosynthesis. This study showed some surprising relationships between plant groups. For example, it showed that "dicotyledons" were not a single, distinct group. At first, scientists were careful about creating a whole new system based on just one gene. But more studies kept showing the same results.

Many scientists worked together on these studies. Instead of naming every single person, they decided to call their new classification the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification, or APG. Their first paper came out in 1998. It got a lot of attention. The goal was to create a classification that everyone could agree on and that would stay stable.

As of 2025, the APG has published three updates: APG II (2003), APG III (2009), and APG IV (2016). Each new version replaced the older one. Many researchers have been part of these papers, either as authors or contributors.

Plant classifications change as new research comes out. But the APG publications are now seen as a very reliable guide. Here are some examples of how the APG system is used:

- Many major plant collections, like those at Kew, are now organized using the APG system.

- The important World Checklist of Selected Plant Families is being updated to follow APG III.

- In the United States, a big photo project of plants is organized by the APG II system.

- In the UK, the 2010 edition of a standard plant guide uses the APG III system.

Main Ideas of the APG System

The APG set out its main ideas for classification in its first paper in 1998. These ideas have stayed the same in all later updates:

- They keep the traditional Linnean system of orders and families. The family is seen as the most important group for flowering plants. Orders help organize families and show how they are related.

- Groups must be monophyletic. This means they must include all the descendants of a common ancestor. The APG rejected older systems because they did not always follow this rule.

- The APG prefers to define groups like orders and families broadly. They think a smaller number of larger orders is more useful. They try to avoid families with only one genus or orders with only one family, if possible. This is only if it doesn't break the rule of being monophyletic.

- For groups above orders and families, they use the term clade. A clade is a group of organisms that share a common ancestor. They say it's not possible or needed to name every single clade. But scientists need to agree on names for some clades, especially orders and families, to talk about them easily.

APG I (1998)

The first APG paper in 1998 was a big deal. It was the first time a large group of organisms was classified mainly based on their genetic features. The paper said that existing classifications were "outdated." The main reason was that they were not phylogenetic. This means they were not based on strictly monophyletic groups.

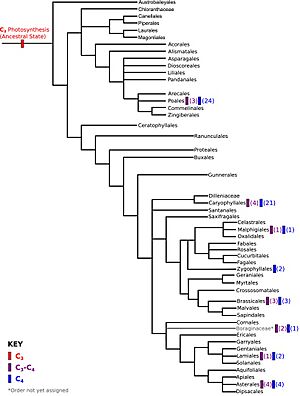

The APG I system recognized 40 orders of flowering plants. This was much fewer than other systems, like Takhtajan's 1997 classification, which had 232 orders.

In 1998, only a few plant families had been studied in detail. The main goal was to agree on names for the higher orders. This was fairly easy to do. But the relationships within these orders were not always clear yet.

Other features of this first classification included:

- They did not use formal scientific names above the level of order. Instead, they used named clades. For example, eudicots and monocots were not given a formal rank.

- Many plant groups that were hard to classify before were now placed in the system. But 25 families still had an "uncertain position."

- For some groups, they offered alternative classifications. This meant some families could be seen as separate or merged into a larger family. For example, the Fumariaceae could be separate or part of Papaveraceae.

A major change was that the traditional division of flowering plants into two groups, monocots and dicots, disappeared. Monocots were recognized as a clade. But dicots were not. Many former dicots were placed in separate groups that came before both monocots and the remaining dicots (called eudicots). The overall plan was simple: a group of early-diverging plants (called ANITA grade), followed by the main groups of flowering plants: monocots, magnolids, and eudicots. The eudicots were a large group with smaller subgroups, including rosids and asterids.

APG II (2003)

As scientists understood the relationships between flowering plant groups better, they focused more on the family level. This included families that were known to be difficult to classify. Again, they reached an agreement easily. This led to an updated classification at the family level. The second APG paper in 2003 updated the 1998 system. The authors said they only made changes when there was "substantial new evidence."

This classification continued to group plants broadly. For example, they tried to put small families with only one genus into a larger group. The authors generally accepted the ideas of specialists. But they noted that specialists often prefer to split groups that look very different.

APG II continued to use "bracketed" taxa. This allowed people to choose between a large family or several smaller ones. For example, the large family Asparagaceae included seven "bracketed" families. These could be seen as part of Asparagaceae or as separate families.

Some main changes in APG II were:

- New orders were created, especially for the "basal clades" that were left as families in the first system.

- Many families that were previously unplaced now had a home within the system.

- Several major families were reorganized.

In 2007, a paper was published that listed the families in APG II in a straight line. This was useful for organizing plant collections in places like herbaria.

APG III (2009)

The third APG paper updated the 2003 system. The main structure of the system stayed the same. But the number of families and genera that were not placed was much smaller. This meant they had to recognize new orders and families compared to the last classification. The number of orders went up from 45 to 59. Only 10 families were not placed in an order. Only two of these (Apodanthaceae and Cynomoriaceae) were left completely outside the classification. The authors said they tried to keep long-recognized families unchanged. They merged families with only a few genera. They hoped this classification "will not need much further change."

A big change was that this paper stopped using "bracketed" families. Instead, they preferred larger, more inclusive families. Because of this, the APG III system had only 415 families, instead of the 457 in APG II. For example, the agave family (Agavaceae) and the hyacinth family (Hyacinthaceae) were no longer seen as separate from the larger asparagus family (Asparagaceae). The authors said that having alternative choices, like in APG I and II, could cause confusion. Major plant collections that were reorganizing agreed to use the more inclusive families. This approach is now widely used in plant collections.

In the same journal, two related papers were published. One gave a linear order of the families in APG III, again for organizing plant collections. The other paper, for the first time, gave formal taxonomic ranks to the groups above the order level. Before, only informal clade names were used.

APG IV (2016)

Developing the fourth version had some disagreements about how to do it. It was harder to reach an agreement than before. Scientists made more progress by using large amounts of genetic information. This included genes from different parts of the plant cell, like plastids, mitochondrials, and the nucleus.

The fourth version was finally published in 2016. It came from a meeting at the Royal Botanical Gardens in 2015. It also included an online survey of botanists and other users. The main structure of the system remained the same. But several new orders were added. Some new families were recognized. Some previously separate families were combined. For example, Aristolochiaceae now includes Lactoridaceae and Hydnoraceae.

Because of naming rules, the family name Asphodelaceae is used instead of Xanthorrhoeaceae. Also, Francoaceae is used instead of Melianthaceae (and now includes Vivianiaceae). This brought the total number of orders to 64 and families to 416 in the APG system. Two new informal major clades, superrosids and superasterids, were also included. APG IV also uses the linear approach for organizing families. A separate file provides an alphabetical list of families by orders.

Updates and Resources

Peter Stevens, one of the authors of all four APG papers, keeps a website called the Angiosperm Phylogeny Website (APWeb). It is hosted by the Missouri Botanical Garden. This website has been updated regularly since 2001. It is a great place to find the latest research on flowering plant family trees that follows the APG ideas. Other helpful resources include the Angiosperm Phylogeny Poster and The Flowering Plants Handbook.

Members of the APG

Many scientists have been part of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group over the years. Here are some of the key members who have contributed to the different APG papers:

| Name | APG I | APG II | APG III | APG IV | Where they worked |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birgitta Bremer | c | a | a | Swedish Academy of Sciences | |

| Kåre Bremer | a | a | a | Uppsala University; Stockholm University | |

| James W. Byng | a | Plant Gateway; University of Aberdeen | |||

| Mark Wayne Chase | a | a | a | a | Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew |

| Maarten J.M. Christenhusz | a | Plant Gateway; Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew | |||

| Michael F. Fay | c | c | a | a | Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew |

| Walter S. Judd | a | University of Florida | |||

| David J. Mabberley | a | University of Oxford; Universiteit Leiden; Naturalis Biodiversity Center; Macquarie University; National Herbarium of New South Wales | |||

| James L. Reveal | a | a | University of Maryland; Cornell University | ||

| Alexander N. Sennikov | a | Finnish Museum of Natural History; Komarov Botanical Institute | |||

| Douglas E. Soltis | c | a | a | a | University of Florida |

| Pamela S. Soltis | c | a | a | a | Florida Museum of Natural History |

| Peter F. Stevens | a | a | a | a | Harvard University Herbaria; University of Missouri-St. Louis and Missouri Botanical Garden |

a = listed as an author (meaning they wrote part of the paper); c = listed as a contributor (meaning they helped with the research or ideas)

See also

In Spanish: Grupo para la filogenia de las angiospermas para niños

In Spanish: Grupo para la filogenia de las angiospermas para niños