W. C. Fields facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

W. C. Fields

|

|

|---|---|

Fields in 1938

|

|

| Born |

William Claude Dukenfield

January 29, 1880 Darby, Pennsylvania, U.S.

|

| Died | December 25, 1946 (aged 66) Pasadena, California, U.S.

|

| Resting place | Forest Lawn Memorial Park, Glendale, California, U.S. |

| Other names | Charles Bogle Otis Criblecoblis Mahatma Kane Jeeves |

| Occupation | Actor, comedian, juggler, writer |

| Years active | 1898–1946 |

| Spouse(s) |

Harriet Hughes

(m. 1900) |

| Partner(s) | Bessie Poole (1916–1926) Carlotta Monti (1933–1946; his death) |

| Children | 2 |

William Claude Dukenfield (born January 29, 1880 – died December 25, 1946), known as W. C. Fields, was a famous American comedian, actor, juggler, and writer. Fields often played characters who seemed a bit grumpy and didn't like children or dogs, but deep down, they were usually kind.

Contents

Fields's Amazing Career

Fields started his career in vaudeville, which was a popular type of stage show with different acts. He became very famous around the world as a silent juggler. Later, he added comedy to his act and was a main comedian in the Ziegfeld Follies, a big Broadway show.

He became a huge star in the Broadway musical Poppy (1923). In this show, he played a charming, small-time trickster. Many of his later roles in plays and movies were similar characters, often funny scoundrels or regular people who were bossed around by their families.

Fields was known for his rough voice and using big, fancy words. People often thought his movie and radio characters were just like him in real life. However, later books showed that Fields was married (though separated from his wife), supported his son, and loved his grandchildren.

His Early Life

William Claude Dukenfield was born in Darby, Pennsylvania. He was the oldest child in a working-class family. His father, James Lydon Dukenfield, came from England. His mother, Kate Spangler Felton, was from a British family.

Claude (as he was called) often argued with his father. He ran away from home many times, starting when he was only nine years old. He usually stayed with his grandmother or an uncle. He didn't go to school very often and stopped after grade school. When he was twelve, he worked with his father selling produce, but after another fight, he ran away again. He worked briefly at a department store and an oyster house.

Fields later told exciting stories about his childhood, saying he lived on the streets of Philadelphia from a young age. But it's believed his home life was actually quite happy. He discovered he was very good at juggling. After seeing a performance at a local theater, he spent a lot of time practicing to become an expert juggler. By age 17, he was living with his family and performing his juggling act in church and theater shows.

In 1904, Fields's father visited him in England while he was performing there. Fields helped his father retire and bought him a summer home. He also encouraged his parents and siblings to learn to read and write so they could send him letters.

Starting in Vaudeville

Fields was inspired by another juggler, James Edward Harrigan, who dressed like a "tramp." In 1898, Fields started performing in vaudeville as a "tramp juggler," using the name W. C. Fields. His family supported his dream and saw him off on the train for his first tour. To hide a stutter, Fields didn't speak on stage at first.

In 1900, he changed his costume and became "The Eccentric Juggler" to stand out. He juggled cigar boxes, hats, and other items. Parts of his act can be seen in his films, like The Old Fashioned Way (1934).

By the early 1900s, people often called him the world's greatest juggler. He became a top performer in North America and Europe, and he toured Australia and South Africa in 1903. When performing for English-speaking audiences, he found he could get more laughs by adding funny comments and sarcastic remarks to his act. He would even "talk" to a ball that didn't come to his hand correctly or mutter funny words to his cigar if he missed his mouth.

Broadway Success

In 1905, Fields made his first appearance on Broadway in a musical comedy called The Ham Tree. This role required him to say lines, which he had never done on stage before. He later said he wanted to be a true comedian, not just a comedy juggler.

In 1913, he performed with the famous actress Sarah Bernhardt. She thought Fields was a great artist who could please any audience. He continued touring in vaudeville until 1915.

Starting in 1915, he joined Florenz Ziegfeld's Ziegfeld Follies show on Broadway. Audiences loved his wild billiards skit, which used strangely shaped cues and a special table for hilarious tricks. This pool game was later shown in some of his films, like Six of a Kind (1934). Fields was a star in the Follies from 1916 to 1922, not as a juggler, but as a comedian in funny sketches. He also starred in the 1923 Broadway musical Poppy, where he perfected his character as a colorful, small-time trickster.

From 1915 on, his stage costume included a top hat, a special coat, and a cane. This costume looked a lot like the comic strip character Ally Sloper.

His Films

Silent Movies and First Talkies

In 1915, Fields starred in two short comedies, Pool Sharks and His Lordship's Dilemma. Because of his busy stage schedule, he didn't make more movies until 1924. Then, he played a small role in Janice Meredith. He also played his Poppy role again in a silent movie called Sally of the Sawdust (1925).

Paramount Pictures then offered Fields a contract to star in his own series of comedies. His next big role was in It's the Old Army Game (1926). This film included a silent version of a scene that would later be expanded in his sound film It's a Gift (1934). His silent films like So's Your Old Man (1926) and Running Wild (1927) were very successful and helped him gain more fans as a silent comedian.

In all his silent films, Fields wore a fake-looking mustache. He kept wearing it even though audiences didn't like it. He wore it in his first sound film, The Golf Specialist (1930), but stopped after his first sound feature film, Her Majesty, Love (1931).

At Paramount Pictures

In the era of sound films, Fields made many movies for Paramount Pictures. In 1932 and 1933, he made four short films for comedy pioneer Mack Sennett. These shorts were based on Fields's stage routines and he wrote them himself. They are considered to show the "essence" of his comedy. For example, in The Dentist, he plays a character who cheats at golf and is very rude to his patients.

His next film, International House, made him a major star. His 1934 classic It's a Gift included another one of his old stage sketches, where he tries to sleep on his back porch but is bothered by noisy neighbors and salespeople. These films often ended happily, with his character getting a sudden fortune that improved his family life.

In 1935, Fields achieved a big goal by playing Mr. Micawber in MGM's David Copperfield. This was a very demanding role.

All this hard work made Fields very ill. He got the flu and had back problems. He was also very sad when two close friends, Will Rogers and Sam Hardy, died suddenly. This made him have a breakdown and he was sick for nine months. The next year, he was asked to play his famous role in Poppy again for a movie. He was very weak during filming, and a body double was often used for long shots. After filming, he became ill again when another friend, Tammany Young, died. Losing three friends in less than a year made Fields very depressed, and he stopped eating. He was in hospitals and sanitariums until the summer of 1937.

In September 1937, Fields returned to Hollywood for Paramount's musical film The Big Broadcast of 1938. He played two almost identical brothers and worked with famous musicians. The film was praised and won an Oscar for best music. However, Fields hated working on the film and often argued with the director, Mitchell Leisen.

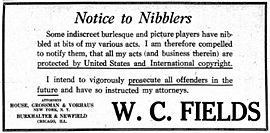

Protecting His Ideas

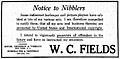

Fields was very protective of his comedy acts and characters. Other performers often copied his sketches. To stop this, Fields started registering his comedy material with the Copyright Office in Washington, D.C., in 1918. But people kept copying him. In 1919, he put a big warning in Variety magazine, telling "Nibblers" (people who copied his work) that his acts were protected by copyright and he would take legal action against anyone who used his material.

Fields continued to protect his comedy material throughout his career, especially for his films. For example, he copyrighted his stage sketch "An Episode at the Dentist's" three times. This sketch later became the short film The Dentist. He also copyrighted "Stolen Bonds," which became scenes in his film The Fatal Glass of Beer. Many of his famous film scenes, like the "Sleeping Porch" scene in It's a Gift, were based on his copyrighted stage material. He copyrighted at least 16 of his most important sketches, which were the foundation of his stage and film career.

His Personal Life

Fields married a chorus girl named Harriet "Hattie" Hughes in 1900. She sometimes helped him on stage, and he would jokingly blame her when he missed a trick. Hattie was well-educated and taught Fields to read and write. Because of her, he became a very enthusiastic reader and always traveled with a trunk full of books, including grammar books and works by famous authors like Shakespeare and Dickens.

They had a son, William Claude Fields, Jr. (1904–1971). Fields was not a religious person, but he agreed to have their son baptized because Hattie wanted it.

By 1907, he and Hattie had separated. She wanted him to stop touring and settle down, but he loved show business too much. They never divorced. Fields continued to write to Hattie and sent her money every week until he died.

Fields met Carlotta Monti (1907–1993) in 1933, and they had a long-term relationship that lasted until his death in 1946. Carlotta Monti later wrote a book about their time together, which was made into a movie.

Illness and Radio Work

In 1936, Fields was very ill. By the next year, he was well enough to make one last film for Paramount, The Big Broadcast of 1938. Fields wanted to use his own jokes in the film, but Paramount told him to stick to the script. Fields refused and was fired. He was very angry about this.

Because he was too sick to work in films, Fields was off the screen for over a year. During this time, he recorded a short speech for a radio show. People loved his familiar voice, and he quickly became a popular guest on radio shows. Even though radio work was less demanding than making movies, Fields still insisted on his movie-star salary of $5,000 per week. He joined ventriloquist Edgar Bergen and his dummy Charlie McCarthy on The Chase and Sanborn Hour for weekly funny routines where they would playfully insult each other.

During his recovery, Fields became closer with his estranged wife and developed a good relationship with his son after his son got married in 1938.

Return to Films

Fields's popularity from his radio shows helped him get a contract with Universal Pictures in 1939. His first film for Universal, You Can't Cheat an Honest Man, continued his funny rivalry with Charlie McCarthy. Fields was so good in the film that he ended up getting top billing.

Fields often argued with studio producers, directors, and writers about his films. He wanted to make a movie his way, with his own script and actors. Universal finally gave him the chance, and the result was Never Give a Sucker an Even Break (1941). This film was a funny, silly look at how Hollywood movies were made. Fields played himself, called "The Great Man." This was Fields's last starring film.

His Final Years

Fields enjoyed spending time at his home with actors, directors, and writers. His close friends included John Barrymore and Gene Fowler. In 1941, a sad accident happened when his neighbors' two-year-old son drowned in a lily pond on Fields's property. Fields was heartbroken and had the pond filled in.

Fields had a large library at home. He enjoyed reading about many subjects.

In a 1994 TV show called Biography, his co-star Gloria Jean remembered talking with Fields at his home. She said he was kind and gentle in person, and she believed he wished for the happy family life he didn't have as a child.

During the 1940 presidential campaign, Fields wrote a funny book called Fields for President, which was like a campaign speech.

Fields's film career slowed down in the 1940s because of his illnesses. He only made short guest appearances in films. He performed his billiard table routine one last time for Follow the Boys (1944), a show for the Armed Forces. In Song of the Open Road (1944), Fields juggled for a few moments and joked, "This used to be my racket." His last film, Sensations of 1945, was released in late 1944. By then, his eyesight and memory were so bad that he had to read his lines from large-print boards.

Fields continued to make radio guest appearances in 1944, where he didn't need to memorize scripts. His last radio appearance was on March 24, 1946. Just before he died, Fields recorded a spoken-word album, which was his final performance.

His Death

Fields spent his last 22 months at a sanatorium in Pasadena, California. He died on Christmas Day, 1946, at age 66, from a serious illness. Carlotta Monti wrote that in his last moments, she sprayed water onto the roof to make it sound like rain, which he loved.

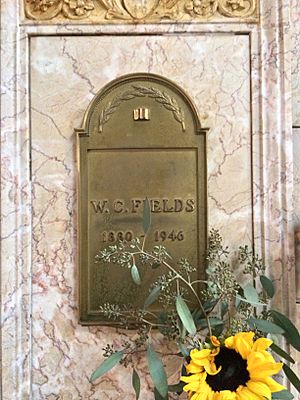

Fields's will asked for him to be cremated. He also wanted to leave part of his money to create a college for orphaned children. After some legal discussions, his remains were cremated on June 2, 1949. His ashes are buried at the Forest Lawn Memorial Park Cemetery in Glendale.

His Gravestone

There's a popular story that his gravestone says, "I'd rather be in Philadelphia." This comes from a funny epitaph Fields wrote for a magazine article in 1925: "Here Lies / W. C. Fields / I Would Rather Be Living in Philadelphia". But in reality, his gravestone only has his stage name and the years he was born and died.

His Comedy Style

Fields often played a "bumbling hero." In films like It's a Gift and Man on the Flying Trapeze, he often wrote or made up most of his own lines and jokes. He frequently used his old stage sketches in his movies. For example, the "Back Porch" scene from the Follies of 1925 was filmed in It's the Old Army Game (1926) and It's a Gift (1934).

Fields's most famous traits included his unique, rough voice, which was not his normal speaking voice. He also often mumbled funny comments under his breath, a habit he copied from his mother. He loved to tease the censors with clever jokes and almost-swear words like "Godfrey Daniels" and "mother of pearl." A favorite funny bit he repeated in many films involved his hat going astray as he tried to put it on his head.

In some of his films, he played carnival barkers or card sharps, telling tall tales and distracting people. In others, he was the victim: a clumsy husband and father whose family didn't appreciate him.

Fields often put parts of his own family life into his films. By the time he started making movies, his relationship with his separated wife was difficult. He believed she had turned their son against him. For example, in Man on the Flying Trapeze, the disapproving mother-in-law was based on his wife, Hattie, and the lazy son was named Claude, after his own son.

Funny Names He Used

Even though he didn't have much formal schooling, Fields read a lot and loved author Charles Dickens, who used unusual character names. Fields collected odd names he found during his travels to use for his own characters. Some examples are:

- "The Great McGonigle" (from The Old-Fashioned Way)

- "Larson E. Whipsnade" (sounds like "larceny," from You Can't Cheat an Honest Man)

- "Egbert Sousé" (sounds like "souse," from The Bank Dick)

Fields often helped write his film scripts using funny fake names. These included "Charles Bogle", "Otis Criblecoblis" (which sounds like "scribble"), and "Mahatma Kane Jeeves" (a play on words).

His Favorite Co-Stars

Fields often worked with a small group of actors in several of his films:

- Elise Cavanna, who had great funny interactions with Fields.

- Kathleen Howard, who often played a nagging wife or someone who opposed him.

- Baby LeRoy, a young child who loved playing pranks on Fields's characters.

- Franklin Pangborn, a fussy, common character actor who appeared in many Fields films.

- Alison Skipworth, who often played his supportive wife.

- Grady Sutton, who usually played a country bumpkin or someone who annoyed Fields's character.

- Tammany Young, who played a clumsy but well-meaning assistant.

His Influence and Legacy

A popular book about Fields, W. C. Fields, His Follies and Fortunes (1949), helped spread the idea that Fields's real personality was just like his grumpy movie characters. However, in 1973, his grandson, Ronald J. Fields, published a book called W. C. Fields by Himself, which used private letters and notes to show that Fields was actually a more complex and kind person.

Woody Allen, a famous comedian, said that Fields was one of six "true comic geniuses" in movie history, along with Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton.

The Surrealists, a group of artists who loved strange and dreamlike things, enjoyed Fields's silly and rebellious humor. Artist Max Ernst even painted a Project for a Monument to W. C. Fields.

Fields is one of the famous faces on the cover of The Beatles' 1967 album Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band.

The United States Postal Service released a special stamp to honor Fields on his 100th birthday in January 1980.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: W. C. Fields para niños

In Spanish: W. C. Fields para niños

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |