William Howard Livens facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

William Howard Livens

|

|

|---|---|

William Howard Livens

|

|

| Born | 28 March 1889 |

| Died | 1 February 1964 (aged 74) London, England |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom |

| Service/ |

British Army |

| Years of service | 1914–1919 |

| Rank | Captain |

| Battles/wars | First World War |

| Awards | Distinguished Service Order Military Cross |

| Other work | Consultant to Petroleum Warfare Department in Second World War |

William Howard Livens (born March 28, 1889 – died February 1, 1964) was a talented engineer, a soldier in the British Army, and an inventor. He is especially known for creating weapons used in chemical warfare and flame warfare. Livens was very clever and good at finding simple solutions. His inventions were practical and easy to make in large numbers.

Livens is most famous for inventing the Livens Projector. This was a simple weapon, like a mortar, that could launch large drums. These drums were filled with flammable liquids or toxic chemicals. During World War I, the Livens Projector became the main way to launch gas attacks. The British army continued to use it until the early years of World War II.

Contents

Early Life of William Livens

William Howard Livens was born to Frederick Howard Livens and Priscilla Abbott. His father, Frederick, was a chief engineer and later the chairman of a company called Ruston and Hornsby in Lincoln. William had two younger sisters.

School and University Years

In 1903, Livens went to Oundle School, a well-known school in England. There, he joined the Officer Training Corps (OTC) and became a sergeant.

After school, from 1908 to 1911, Livens studied at Christ's College, Cambridge at the University of Cambridge. He also joined the college's OTC as a private. He was an excellent shot with both rifles and pistols. He even set a record score in a rifle competition against Oxford University.

Livens trained to be a civil engineer. For a short time, he worked as an assistant editor for Country Life magazine. But when World War I began, he joined the British Army.

William Livens and World War I

Joining the Army

On August 4, 1914, after finishing his Officer Training Corps program, Livens applied to join the Royal Engineers. He became a second lieutenant on September 30, 1914. His first job was a clerical role in the Motorcycle signalling section at Chatham. Livens' training and his love for target shooting helped him in the army.

He was very skilled with a revolver. Once, during a shooting lesson, the sergeant didn't know how good Livens was. The sergeant carefully explained how to shoot. Livens then fired 10 shots. After each shot, the sergeant kept saying, "Sorry, Sir, you're not yet on the target." After all 10 shots, Livens suggested they look closer. All 10 shots had hit the very center of the target!

Designing New Weapons

Early Ideas

Army life did not stop Livens from being creative. He started thinking about how to make better weapons. On his own, he set up small labs in his barracks bedroom and the officers' garage at Chatham. He used empty land near old forts to test his inventions. Here, he worked on creating flame throwers and small mortars to launch oil and gas.

Livens' inventive work was driven by a strong desire to respond to German actions during the war. After the Germans first used poison gas at the Second Battle of Ypres in April 1915, Livens began his experiments. He wanted to create new ways to fight back effectively.

Special Gas Companies

In August 1915, Livens joined one of the new Royal Engineer Special Gas Companies. He was one of the few officers with an engineering background, not chemistry. At that time, gas warfare was very basic. Heavy cylinders of poison gas were carried to the front trenches. Their contents were simply released through pipes, hoping the wind would carry the gas over enemy lines. But the wind was unreliable. The first British gas attack at the Battle of Loos was a failure because the wind changed direction.

Livens improved this system. He developed long rubber hoses to carry the gas to the best release spot. He also created a device that connected four gas cylinders to one pipe. These changes made the gas attacks more reliable.

Livens was known for getting things done. He once needed supplies quickly and managed to get 20 lorries (trucks) by directly contacting a high-ranking officer. This showed his determination, even if it sometimes surprised his commanders.

Livens was soon put in charge of Z Company. This special unit was tasked with developing a British version of the German flamethrower. Four of Livens' huge, fixed flame projectors, called the "Livens Large Gallery Flame Projector," were planned for use on July 1, 1916, at the start of the Battle of the Somme. Two were destroyed by German artillery before they could be used. The other two were effective in scaring the German defenders. However, these large flamethrowers had a limited range and could not be moved easily. This made them useful only in very specific situations. They were only used one more time in 1917. The remains of one of these projectors were found and dug up in 2010.

The Livens Projector

One day during an attack on the Somme, Z Company faced German soldiers who were well hidden in dugouts. Regular grenades didn't work. So, Livens threw in two five-gallon oil drums. The burning oil was so effective that Livens' friend, Harry Strange, wondered if it would be better to use containers to carry fire to the enemy instead of complex flamethrowers.

Thinking about this, Livens and Strange considered how to launch a very large shell filled with fuel. The main idea of throwing a large oil container came from Strange. But Livens went on to develop a simple, large mortar that could launch a three-gallon oil drum. The drum would burst when it landed.

His new weapon was first used on July 23, 1916. Twenty oil projectors were fired before an attack at Pozières during the Battle of the Somme. The effect was limited. Next, thirty projectors were fired at High Wood on August 18, with better results. Another attack on September 3 was very successful.

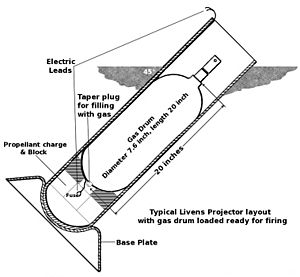

After these attacks, Livens got the attention of General Gough. Gough was impressed by his ideas and helped him get everything he needed. The new weapon became the Livens Projector. It was a simple tube, closed at one end. It was half-buried in the ground at a 45-degree angle, pointing in the desired direction. It was loaded with a single shot and enough propellant to reach the target.

Setting up many projectors for an attack took a lot of planning. But this was not a big problem in the static trench warfare conditions. The weapon was so simple and cheap that hundreds, sometimes thousands, of projectors could be fired at the same time. This often surprised the enemy. Z Company quickly improved the Livens Projector. They increased its range from 180 meters (200 yards) to 320 meters (350 yards). Eventually, they made an electrically triggered version with a range of 1,190 meters (1,300 yards).

The Livens Projector was changed to fire canisters of poison gas instead of oil. This system was secretly tested at Thiepval in September 1916 and Beaumont-Hamel in November. The Livens Projector could deliver a high concentration of gas a long distance. Each canister delivered as much gas as several chemical warfare artillery shells.

The Livens Projector was used in several gas attacks in October 1916. Livens himself watched some firings from an aircraft. He reported that if projectors were used on a large scale, the cost of "killing Germans" could be greatly reduced. This report was sent to the Ministry of Munitions. Livens was soon sent back to England to help develop a standard projector and drum. The Livens Projector became the preferred way for the British Army to launch chemical attacks. Its production was given high priority. Over 150,000 units were produced for the Allies during the war. Livens, who was "always full of ideas," became a link between the Special Brigade and the Ministry of Munitions for the rest of the war.

Other Inventions

Livens kept improving his projector and designing other weapons for trench warfare. Some were useful, others were not. For example, he tried to cut barbed wire using large amounts of explosives. This system failed because the explosives often blew up in the air without effect.

Livens' ideas for cutting wire were simple but did not succeed. However, he was never discouraged if a weapon didn't work as expected.

Awards and Leaving the Army

Livens' work was dangerous, and he was very brave. Once, while testing a gas mask against Hydrogen sulfide gas, the gas got through. Livens passed out but quickly recovered. During the war, Livens received the Military Cross on January 14, 1916, and the Distinguished Service Order on January 1, 1918.

Livens left the army on April 11, 1919.

Between the World Wars

After World War I, Livens had his own money, so he didn't need to invent new things. His life became quieter. In 1919, Livens and his father patented an improved projectile. They made it stronger but lighter using special manufacturing methods.

In 1920, Livens applied to the Royal Commission on Awards to Inventors for his wartime work on flamethrowers and the Livens Projector. He had to wait for a hearing, which was complicated because his old friend Harry Strange also claimed part of the invention. The hearing was held on May 27, 1922. By then, Livens had agreed to share any award with Strange. Livens was awarded £500 for his flamethrower work and £4,500 for the Livens Projector and its ammunition. This was a large sum of money at the time.

William Livens and World War II

When World War II started, Livens was offered a high rank in the Royal Air Force. However, he chose to help as a civilian. This way, he was free to disagree with higher-ups if he thought it was necessary.

In 1940, as a German invasion of Britain seemed possible, the British developed new flame weapons. Livens joined the team at the new Petroleum Warfare Department. Sir Donald Banks, who led the department, described Livens as a "typical inventor." He would pull explosives, fuses, wires, and gadgets from his pockets, and surprising explosions would happen in unexpected places.

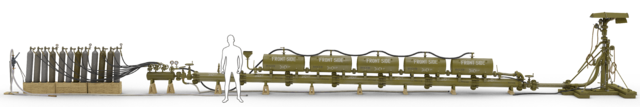

The Petroleum Warfare Department tested several ideas, including some from Livens. One promising idea was the flame fougasse, which was widely adopted.

A flame fougasse was a 40-gallon steel drum filled with a petroleum mixture. It had a small, electrically detonated explosive charge to propel the flame. The barrel was buried by the roadside and camouflaged. When the explosive charge went off, it burst the barrel and shot a flame 3 meters (10 feet) wide and 27 meters (30 yards) long.

Tens of thousands of flame fougasse barrels were set up. Most were removed after the war, but a few were missed. Their remains can still be found today. The flame fougasse has remained in army manuals as a simple, effective battlefield weapon ever since.

Personal Life

Livens married Elizabeth Price around 1916, and they had three daughters. Elizabeth died in 1945 after a long illness. In 1947, Livens married Arron Perry.

In 1924, Livens invented a small dishwasher for homes. It had all the features of modern dishwashers, like a front door, a wire rack for dishes, and a spinning sprayer. According to his family, Livens built a working model for his home. But when their maidservant tried it, she was found crying with water flooding the floor. So, the experiment was stopped.

In his free time, Livens enjoyed sailing small boats. He was a member of the Royal Thames Yacht Club. Livens also became interested in Spiritualism, attending several séances. He was an honorary vice-president of the Spiritualist Association of Great Britain. He was also a good friend of Lord Dowding, who shared similar interests. Livens was briefly interested in photography and patented inventions related to it in the 1950s.

William Howard Livens passed away in a London hospital on February 1, 1964. He was cremated on February 8. His family asked that donations be made to Cancer Research instead of sending flowers. He was survived by his three daughters.

|

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |