British anti-invasion preparations of the Second World War facts for kids

During World War II, from 1940 to 1941, Britain faced a huge threat: Nazi Germany planned to invade. This plan was called Operation Sea Lion. To prepare, Britain launched a massive effort involving both soldiers and regular people. The British Army had just suffered a big defeat in France during the Battle of Dunkirk. So, 1.5 million men joined the Home Guard, a part-time army. Many new defences were built quickly, turning much of the UK, especially southern England, into a prepared battlefield. Luckily, Operation Sea Lion never happened. Today, most of these defences are gone, but you can still find strong concrete structures like pillboxes and anti-tank blocks, especially near the coast.

Contents

Why Britain Prepared for Invasion

The Start of World War II

On 1 September 1939, Germany invaded Poland. Two days later, Britain and France declared war on Germany, starting World War II. The British Expeditionary Force (BEF) was sent to the border between France and Belgium. For several months, there wasn't much fighting. This time was known as the "Phoney War". Soldiers trained, and France and Britain built defences.

Growing Fears of Invasion

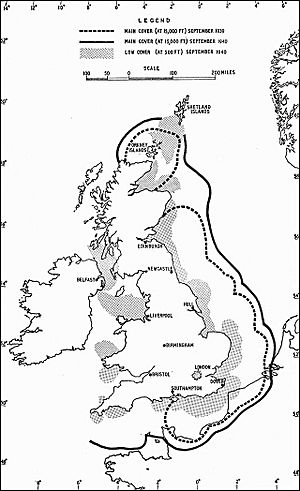

British leaders became worried about reports of large German airborne forces. These forces could attack Britain from the air. Winston Churchill, who was in charge of the navy at the time, asked General Sir Walter Kirke to create a plan to stop a big invasion. Kirke's plan, called "Plan Julius Caesar," was ready in November 1939. He had limited resources, with only a few poorly trained army divisions in England and Scotland. Kirke thought the eastern coasts of England and Scotland were most at risk.

Germany's Successes in Europe

On 9 April 1940, Germany invaded Denmark and Norway. Denmark quickly surrendered. After a short fight, Norway also fell. This showed Britain that Germany could successfully attack across the sea. This worried the British. On 10 May 1940, Germany invaded France. The BEF and French forces were pushed back. German Panzer (tank) divisions moved quickly through the Ardennes Forest. Most of the BEF managed to escape to Dunkirk, a French port. With Germans now on the French coast, it became clear that Britain urgently needed to prepare for an invasion.

Britain's Armed Forces Get Ready

The British Army After Dunkirk

From 26 May 1940, British and French soldiers were rescued from Dunkirk in Operation Dynamo. Over ten days, 338,226 soldiers were brought to Britain. Most of their vehicles, tanks, guns, and equipment were left behind in France. Some soldiers even returned without their rifles. Another 215,000 soldiers were rescued from other French ports in June.

By June 1940, the British Army had 22 infantry divisions and one armoured division. Many divisions were at half strength and lacked artillery. They had some older guns and received hundreds of 75mm guns from the US. There was also a big shortage of ammunition for training.

The number of tanks in Britain grew quickly between June and September 1940.

| Date | Light tanks | Cruisers | Infantry tanks |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 Jun 1940 | 292 | 0 | 74 |

| 1 Jul 1940 | 265 | 118 | 119 |

| 4 Aug 1940 | 336 | 173 | 189 |

| (sent to Egypt) |

(−52) | (−52) | (−50) |

| 27 Aug 1940 | 295 | 138 | 185 |

| 15 Sept 1940 | 306 | 154 | 224 |

These numbers don't include training tanks or those being repaired. The light tanks were mostly MkVIB, and cruiser tanks were A9 / A10 / A13. The infantry tanks included the strong Matilda II.

Churchill said that by mid-September, Britain had 16 high-quality divisions ready, including three armoured divisions. Britain even sent 154 tanks to Egypt in mid-August. British factories were making almost as many tanks as Germany, and by 1941, they would make even more.

The Home Guard

On 14 May 1940, the Local Defence Volunteers (LDV) were created. They later became known as the Home Guard. Many more men volunteered than expected, nearly 1.5 million by the end of June. There were plenty of people, but not enough uniforms or equipment. At first, the Home Guard used their own guns, knives on poles, and homemade Molotov cocktails.

By July 1940, things improved. Volunteers received uniforms and some training. Britain bought 500,000 modern M1917 Enfield Rifles and 25,000 M1918 Browning Automatic Rifles from the US. New weapons were also developed that were cheap to make, like the No. 76 Special Incendiary Grenade, a glass bottle filled with flammable material.

The sticky bomb was a glass flask with nitroglycerin and a sticky coating. It was meant to be thrown onto enemy vehicles. It was hard to use effectively, but an order for one million was placed. The Home Guard also got some armoured cars, some of which were made from regular vehicles with added steel plates. By 1941, they had special anti-tank weapons like the Blacker Bombard and the Smith Gun.

The Royal Air Force

In mid-1940, the Royal Air Force (RAF) fought the German Luftwaffe for control of British airspace. The Germans needed to control the skies to invade. If the Germans had won, the RAF would have had to fly from airfields far from southeast England. Any airfield in danger would have been destroyed.

The RAF had a plan called Operation Banquet. It meant almost any available aircraft, even trainer planes like the De Havilland Tiger Moth, would be used as bombers. They would drop small bombs from simple racks.

Before the war, the Chain Home radar system was installed in southern England. The Germans didn't realize how effective this system was. It became very important for Britain's defence during the Battle of Britain. By the start of the war, about 20 Chain Home stations were built. Chain Home Low stations were also built to detect aircraft flying at lower heights.

The Royal Navy was much larger than the German Kriegsmarine, but it had many duties around the world. The Royal Navy could defeat any German naval force, but it needed time to gather its ships. On 1 July 1940, many ships were on escort duties or in northern ports.

However, ten destroyers were immediately available at southern ports like Dover and Portsmouth. More destroyers were moved to defend Britain by the end of July. By early September, the Royal Navy had 4 light cruisers and 57 destroyers along the south coast. This force was much larger than what the Germans had for naval escorts.

Building Defences on Land

Britain started a huge program to build defences. On 27 May 1940, the Home Defence Executive was formed to organize Britain's defence. At first, defences were mostly static, focusing on the coastline and a series of inland anti-tank "stop lines". The longest and strongest was the GHQ Line, a line of pillboxes and anti-tank trenches from Bristol to York. It was meant to protect London and England's industrial areas.

Military thinking changed quickly. General Sir Edmund Ironside had to use static defences because of a lack of equipment and trained men. But it was soon clear this wasn't enough. Churchill wasn't happy with Ironside's progress. General Alan Brooke replaced Ironside on 19 July 1940.

Brooke changed the focus from stop lines. He ordered that cement be used mainly for beach defences and "nodal points." These nodal points, also called anti-tank islands, were strong points meant to hold out for up to seven days.

Coastal Defences

The south and east coasts of England were most vulnerable. In 1940, 153 new coastal batteries were built to protect ports and landing spots. They used guns from old naval ships. Some had very little ammunition. At Dover, two huge 14-inch guns, called Winnie and Pooh, were used.

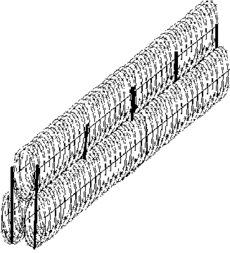

Beaches were blocked with barbed wire, often in three coils, and minefields with anti-tank and anti-personnel mines. Parts of Romney Marsh, a planned invasion site, were flooded. Piers, which could be used to land troops, were taken apart or blocked.

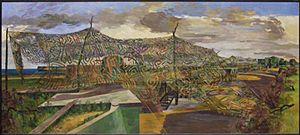

To stop tanks, Admiralty scaffolding was built. This was a 9-foot-high fence of scaffolding tubes placed at low tide. It was used along hundreds of miles of beaches.

Pillboxes of different types overlooked the beaches. Some were low for better firing angles, others were high up to make them harder to capture. Searchlights lit up the sea and beaches for artillery. Many small islands were also fortified to protect important targets.

Inland Lines and Islands

The main goal of stop lines and anti-tank islands was to slow down the enemy and limit their attack routes. Stopping tanks was key. Defences often followed natural barriers like rivers, canals, railway lines, and thick woods. Where possible, land was flooded to make it too soft for vehicles.

Thousands of miles of anti-tank ditches were dug, usually 18 feet wide and 11 feet deep. Other barriers were made of huge concrete blocks: cubes, pyramids, or cylinders. Cubes were usually 5 or 3.5 feet high. Sometimes, anti-tank walls were built from connected cubes.

"Pimples," also known as Dragon's teeth, were pyramid-shaped concrete blocks designed to make tanks expose their weak spots. They were typically 2 feet high. Cubes, cylinders, and pimples were placed in long rows to form barriers on beaches and inland. They were also used to block roads.

Roads were blocked at important points. Many roadblocks were designed to be removable. Simple ones were concrete anti-tank cylinders that could be moved into place. Other removable roadblocks used strong metal beams placed in sockets in the road. Similar blocks were used on railway tracks. These blocks could be opened or closed in minutes.

Another system used mines placed in shallow pits in the road. When not in use, these pits were covered. Bridges and other key points were prepared for demolition with explosives. A "Depth Charge Crater" was a spot in a road with buried explosives that could create a deep hole instantly. The Canadian pipe mine could ruin a road or runway quickly. These hidden demolitions meant the enemy couldn't prepare for them.

Crossing points like bridges and tunnels were called "nodes" or "points of resistance." They were fortified with removable roadblocks, barbed wire, and land mines. These defences were protected by trenches, gun positions, and pillboxes. Some villages were even fortified with barriers and sandbagged positions.

Nodes were given 'A', 'B', or 'C' ratings based on how long they were expected to hold out. Home Guard troops usually defended the nodal points. Regular troops defended Category 'A' points.

Construction was very fast. By the end of September 1940, 18,000 pillboxes and many other defences were finished. Some old castles and forts were updated with new defences. About 28,000 pillboxes and other strong defences were built in the UK, and about 6,500 still exist. Some were even disguised to look like haystacks or churches.

Airfields and Open Areas

Open areas were thought to be vulnerable to air invasion by paratroopers or gliders. Open areas with a straight length of 500 yards or more near the coast or an airfield were blocked with trenches, wooden or concrete obstacles, or old cars.

Airfields were very vulnerable and were protected by trenches and pillboxes facing inwards towards the runway. These defences were designed to stop light weapons and offer all-round visibility. It was hard to defend large open areas without stopping friendly aircraft. Solutions included the pop-up Pickett-Hamilton Fort, a light pillbox that could be lowered into the ground.

Another idea was the Bison concrete armoured lorry, a truck with a concrete armoured cabin and a small concrete pillbox on the back. A "runway plough" was also built in Canada and assembled in Scotland. It was designed to rip up runways and railway lines to make them useless to invaders.

Other Ways Britain Prepared

Basic defensive steps included removing road signs and railway station signs to confuse the enemy. Petrol pumps near the coast were removed, and plans were made to destroy others. Detailed plans were ready to destroy anything useful to invaders, like port facilities or key roads. In some areas, many people were moved away from the coast. For example, 40% of people in Kent and 50% in East Anglia were relocated.

The public was told what to do. In June 1940, the Ministry of Information published a leaflet called If the Invader Comes, what to do—and how to do it. It told people to "stay put" unless ordered to evacuate, so roads wouldn't be blocked by refugees. People were warned not to believe rumors and to report anything suspicious. They were also told to deny useful things like food, fuel, or maps to the enemy. They should be ready to block roads with trees or cars if ordered.

On 13 June 1940, church bells were banned. They would only be rung by the military or police to warn of an invasion, usually by paratroopers.

People were expected to do more than just resist passively. Churchill imagined people running up to tanks and sticking bombs on them, even if it cost them their lives. He even told his wife and daughter-in-law that he expected them to kill Germans, suggesting a butcher knife if they didn't have a gun.

In 1941, "invasion committees" were formed in towns and villages. They worked with the military to plan for the worst if their communities were cut off or occupied. These committees kept secret "War Books" with plans for emergencies, including where to bury the dead. They were told that "every citizen will regard it as his duty to hinder and frustrate the enemy."

The police also had new roles. Many younger officers joined the armed forces, and retired officers were called back. Police, who are usually unarmed in Britain, were trained to use firearms to guard important sites and defend their stations. They were also told to conduct armed patrols if an invasion happened. Churchill wanted police and air raid wardens to fight alongside the Home Guard.

Special Weapons and Deception

New Weapons and Petroleum Warfare

In 1940, Britain was very short on weapons, especially anti-tank guns. The Sten submachine gun was developed to help. One resource Britain had plenty of was petroleum oil. A lot of effort went into using it as a weapon. Many flamethrowers were improvised from car repair equipment.

"Flame traps" were also created. A mobile flame trap used trucks with large fuel tanks to spray burning liquid into sunken roads. Static flame traps used pipes along roads connected to elevated fuel tanks.

A flame fougasse was a 40-gallon steel drum filled with petroleum mixture and a small explosive. It was buried by the roadside and camouflaged. When triggered, it would shoot a jet of flame 10 feet wide and 30 yards long. These were usually placed in groups of four where vehicles would have to slow down. About 50,000 flame fougasse barrels were installed at 7,000 sites in southern England and 2,000 in Scotland.

Experiments were done with igniting oil on the sea. By early 1941, a "flame barrage" technique was developed. Nozzles above the high-water mark sprayed fuel, creating a roaring wall of flame over the water. These were impressive but used a lot of resources. German aircraft observed some tests, and Britain used this to spread propaganda about the effects of these petroleum weapons.

It's likely Britain would have used poison gas on beaches. General Brooke stated he "had every intention of using sprayed mustard gas on the beaches." Mustard gas, chlorine, and other gases were made and stored at key points and airfields. Bombers and crop sprayers would spray landing craft and beaches with these gases.

Hiding and Tricking the Enemy

Britain not only built real defences but also tried to make the enemy believe there were more defences than there were. Drain pipes stood in for real guns, fake pillboxes were built, and uniformed mannequins stood guard.

Volunteers were encouraged to use anything to delay the enemy. They used existing walls or buildings to create barriers with chains and cables. They even attached fake bombs to these barriers to make them look more threatening. Concrete cylinders were ready to be rolled into roadways.

A secret section, funded by MI6, was created in 1938 to spread propaganda. It later became part of the Special Operations Executive (SOE) and then the Political Warfare Executive in 1941. Their job was to spread false rumors and conduct psychological warfare. After seeing a demonstration of petroleum weapons, they spread a false rumor that Britain had a new bomb that would spread a thin film of burning liquid on the water. This rumor was so believable that German pilots thought it was true.

Secret Resistance Plans

Auxiliary Units

The War Office didn't take the invasion threat seriously until France fell in May 1940. However, the Secret Intelligence Service had been planning since February 1940, creating a secret resistance network. In May 1940, they also started hiding weapons and recruiting for a civilian guerrilla group. The War Office then created the Auxiliary Units as a more military option.

Auxiliary Units were a secret, specially trained group of commandos. They would attack the enemy's sides and rear. They were made up of regular army "scout sections" and patrols of 6-8 men from the Home Guard. Each patrol was self-sufficient and had a hidden underground base, usually in woodlands. They were expected to operate for about 14 days during an invasion.

The Auxiliary Units also included civilian "Special Duties" personnel. Their job was to gather intelligence, spying on enemy movements. Reports were left at secret drop-off points or sent by hidden radio operators.

Attacking German Invasion Plans

Britain's leaders didn't just wait for Germany to attack. They made big efforts to attack German ships gathered in occupied ports between The Hague and Cherbourg, starting in July 1940. These attacks were called the "Battle of the Barges." Here are some notable operations:

- 12 August: Five Handley Page Hampden bombers attacked the Ladbergen Aqueduct in Germany. This blocked a waterway for ten days, stopping barges from moving towards the Channel.

- 8 September: British cruisers and destroyers attacked Boulogne harbour in France. Motor Torpedo Boats also attacked a convoy off Ostend, sinking two transport ships.

- 10 September: Three destroyers found a convoy off Ostend and sank an escort vessel, two trawlers, and a large barge.

- 13 September: An RAF bombing raid destroyed 80 barges at Ostend.

- 15 September: Sergeant John Hannah won the Victoria Cross during an RAF bombing raid on barges at Antwerp.

- 17 September: A major attack by Bomber Command on ports along the occupied coast. 84 barges were damaged at Dunkirk.

- 26 September: Operation Lucid, a plan to send fire ships into Calais and Boulogne harbours to destroy barges, was cancelled due to problems with the old tankers.

- 30 September: The warship HMS Erebus fired 17 large 15-inch shells onto Calais docks.

- 10–11 October: Operation Medium, an attack on invasion transports in Cherbourg. While RAF bombers distracted German defences, a Navy force approached and fired 120 15-inch shells and 801 4.7-inch shells. The Germans fired back but didn't hit any British ships.

Between 15 July and 21 September, German records show that 21 transport vessels and 214 barges were damaged by British air raids.

The Invasion Threat Fades

After Dunkirk, people thought an invasion could happen any day. Churchill himself was sometimes worried about Britain's chances. German preparations would take weeks, but Britain built defences with extreme urgency. The weather usually gets worse after September, but an October landing was still possible. On 3 October, General Brooke wrote in his diary, "Still no invasion! I am beginning to think that the Germans may after all not attempt it."

Britain won the Battle of Britain. On 12 October 1940, Hitler secretly postponed Operation Sea Lion until early 1941. By then, Britain's defences were much better. More trained soldiers and equipment were available, and fortifications were ready. With growing confidence, Churchill famously said, "We are waiting for the long promised invasion. So are the fishes..."

When Germany invaded the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941 (called Operation Barbarossa), it seemed unlikely they would invade Britain while fighting Russia. In July 1941, building new defences slowed down. The focus shifted to preparing for smaller raids rather than a full invasion.

On 7 December 1941, Japan attacked the American fleet at Pearl Harbor. The United States entered the war on Britain's side. With America's "Germany first" strategy, resources poured into the UK. This effectively ended the danger of invasion after two years.

How Effective Were the Defences?

General Brooke often wrote his concerns in his private diary. He later added notes saying he believed the invasion was a real threat. He felt Britain's land forces weren't enough, but he also believed they would succeed in defending the country.

It's a big question whether the defences would have worked. In mid-1940, Britain relied heavily on fortifications. While attacking prepared defences was hard, German tanks had easily overrun similar defences in Belgium. Britain also lacked many weapons after Dunkirk. However, German invasion plans were also rushed. Their fleet of 2,000 converted barges was questionable. Until Germans captured a port, both armies would have lacked tanks and heavy guns.

Later battles, like the Dieppe Raid in 1942 and the D-Day landings, showed that defenders could cause huge losses to attacking forces. This would delay the enemy until reinforcements could arrive by sea and land.

The Royal Navy would have sailed to the landing places, possibly taking several days. The German Navy had been badly weakened by the Norway campaign. It lost many ships and had few heavy units left. The Germans planned to land on the southern coast of England, hoping to block the narrow English Channel with mines and submarines to stop the Royal Navy. While German air and naval forces could have caused damage to the Royal Navy, they couldn't have stopped Britain from bringing in more troops and supplies. In this situation, British land forces would have faced the Germans on more equal terms. They only needed to delay the German advance until the Royal Navy could cut off German supplies, then launch a counterattack.

Experts and war games, like the 1974 Royal Military Academy Sandhurst war game, agree that German forces could have landed and gained a beachhead. But the Royal Navy's intervention would have been decisive. Even with the best assumptions for Germany, their army would not have gotten past the GHQ Line and would have been defeated.

After failing to gain control of the air in the Battle of Britain, Operation Sea Lion was postponed indefinitely. Hitler and his generals knew the invasion problems. Many experts believe German invasion plans were just a trick and never meant to happen.

While Britain might have been militarily safe in 1940, both sides knew a political collapse was possible. If Germany had won the Battle of Britain, the Luftwaffe could have attacked anywhere in southern England. With the threat of invasion, the British government might have been pressured to make peace. However, the extensive anti-invasion preparations showed Germany and the British people that Britain was ready and willing to defend itself, no matter what happened in the air.

See also

- Coats Mission

- Eastbourne Redoubt, home of the Combined Service Museum

- Dymchurch Redoubt

- Operation Lucid

- Atlantic Wall

- British County Divisions, regular infantry divisions raised for static and coastal defence duties

Images for kids

-

Inchgarvie just below the Forth Bridge

-

Sockets for a hedgehog removable roadblock on a bridge over the Kennet and Avon Canal.

-

Sockets for anti-tank mines on a bridge over the Basingstoke Canal.

-

Removable roadblock buttress on the Taunton Stop Line

-

Demolition chambers under a bridge over the Bridgwater and Taunton Canal—later filled with concrete

-

A flame fougasse demonstration somewhere in Britain. A car is surrounded in flames and a huge cloud of smoke. circa 1940.

-

This Blenheim Mark VI bomber of No. 40 Squadron RAF was lost with its crew during a raid on German invasion barges at Ostend on 8 September 1940.

-

HMS Jupiter fires her 4.7-inch guns during Operation Medium, the bombardment of Cherbourg on 10 October 1940.