William Schaw facts for kids

William Schaw (around 1550–1602) was a very important person in Scotland. He was the Master of Works for James VI of Scotland, which meant he was in charge of building and fixing all the King's castles and palaces. People also believe he played a big part in how Freemasonry in Scotland developed.

Contents

Who Was William Schaw?

William Schaw was the second son of John Schaw of Broich, a place now called Arngomery near Kippen in Stirlingshire. His family had connections to the King's court, often helping with the King's wine cellar.

When William was young, he might have been a page at the court of Mary of Guise, who was the Queen's mother and ruled Scotland for a time. During this period, he would have been in Edinburgh Castle while it was being made stronger.

Later, around 1580, William Schaw was noted as the "clock-keeper" for Esmé Stewart, 1st Duke of Lennox, a close friend of the King.

In 1581, William was given valuable land rights in Kippen. In 1583, he traveled to Paris when Esmé Stewart died.

Becoming the Master of Works

On December 21, 1583, King James VI chose William Schaw to be the main Master of Works for Scotland for the rest of his life. This meant he was in charge of all royal castles, palaces, and building projects. He was also responsible for planning and directing any new projects for the King.

In November 1583, Schaw went on a diplomatic trip to France with Lord Seton and his son Alexander Seton. The Seton family were known supporters of Mary, Queen of Scots. When Schaw returned in 1584, he helped the Seton family with their own building projects.

In 1585, he helped entertain three Danish ambassadors visiting the Scottish court. Later, in the 1590s, some people suspected William Schaw of being a Roman Catholic and having anti-English views.

By May 1596, William Schaw was listed as 'Praefectum Architecturae' (Chief Architect) for the King. He had also gained control of the land of Sauchie.

Records show that Schaw supervised building work at places like Falkland Palace and Stirling Castle. In 1599, he oversaw major repairs at Holyrood Palace. This work involved masons, roofers, plumbers, and carpenters fixing the court, kitchens, the steeple, the clock, and even the King's billiard table! Schaw would sign off on the work every week as "Maistir of Wark."

In 1601, King James VI sent William to discuss building a monument to celebrate the King's escape from the Gowrie House conspiracy, a plot against him.

Working for Queen Anna

In 1589, William Schaw was among the people who went with King James VI to Denmark to bring back his new queen, Anna of Denmark. Schaw returned to Scotland early in 1590 to get everything ready for the Queen's arrival. He even brought a Danish carpenter named Frederick to join the Queen's household.

Schaw was very busy repairing Holyrood Palace and Dunfermline Palace, which were given to the Queen. He used money from taxes and a gift from Queen Elizabeth of England to pay for these repairs. He also planned the special ceremony to welcome Queen Anna when she arrived at Leith and decorated St Giles' Kirk with beautiful tapestries for her coronation. Because of this, he became the Master of Ceremonies for the court.

In June 1590, Schaw helped his relative James Gibb, who had been involved in a fight.

In 1593, Schaw was involved in talks with Danish ambassadors about Queen Anna's property rights. On July 6, he was made Chamberlain of Dunfermline, an important role in Queen Anna's household. He worked closely with Alexander Seton and William Fowler, managing accounts for the Queen's jewels and collecting rents from her lands.

William Schaw also directed changes at Dunfermline Abbey. He is believed to have built a steeple and a porch, added supports to the outside, and prepared the inside for Presbyterian church services between 1594 and 1599.

In 1594, King James VI and Queen Anna built a new Chapel Royal at Stirling Castle. This building was used for the christening of their son, Prince Henry. Although not directly mentioned, Schaw likely oversaw this project. For New Year's Day in 1595, the Queen gave him a special hat badge: a golden salamander with diamonds.

In March 1598, Schaw was asked to give the Queen's brother, Ulrik, Duke of Holstein, a tour of Scotland. He took him to places like Fife, Ravenscraig Castle, Dundee, and Stirling Castle.

His Later Life and Death

William Schaw died in 1602. His friend Alexander Seton and Queen Anne paid for his tomb, which is still at Dunfermline Abbey. The tomb has a long Latin message that talks about how smart and skilled he was. It says he was a man of great honesty and kindness, excellent at architecture, and loved by everyone who knew him.

The message on his tomb also says: "This humble structure of stones covers a man of excellent skill, notable honesty, singular integrity of life, adorned with the greatest of virtues – William Schaw, Master of the King's Works, President of the Sacred Ceremonies, and the Queen's Chamberlain. He died 18th April, 1602.

Among the living he dwelt fifty-two years; he had travelled in France and many other Kingdoms, for the improvement of his mind; he wanted no liberal training; was most skilful in architecture; was early recommended to great persons for the singular gifts of his mind; and was not only unwearied and indefatigable in labours and business, but constantly active and vigorous, and was most dear to every good man who knew him. He was born to do good offices, and thereby to gain the hearts of men; now he lives eternally with God.

Queen Anne ordered this monument to be erected to the memory of this most excellent and most upright man, lest his virtues, worthy of eternal commendation, should pass away with the death of his body."

After his death, David Cunninghame of Robertland took over as the King's Master of Works. Years later, in 1612, it was found that William Schaw was still owed his annual payment for several years of his service.

Rules for Stonemasons

William Schaw is famous for creating important rules for stonemasons, which are called the "Schaw Statutes." These rules helped organize the craft of masonry in Scotland.

First Schaw Statutes

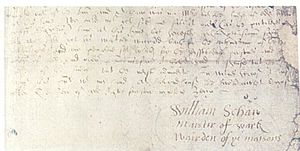

On December 28, 1598, William Schaw, as the Master of Works and the main leader of the master stonemasons, issued "The Statutes and Ordinances to be observed by all the Master Masons within this Realm." These rules were agreed upon by all the master masons gathered that day.

The first rule said that master masons in Scotland should: "observe and keep all the good ordinances set down of before, concerning the privileges of their craft, to their predecessors of good memory, and specially, they be true one to another, and live charitably together, as becomes sworn brothers and companions of craft."

These rules set up a system of leaders like wardens, deacons, and masters. They made sure that masons only took on work they could do well. They also set limits on how many apprentices a master mason could have (usually three in a lifetime) and how long apprentices had to train (seven years). There were also rules for how many master masons and apprentices needed to be present for a new master to join the craft.

Copies of these rules were sent to every stonemason lodge in Scotland. These statutes greatly improved how the stonemason craft was organized.

Second Schaw Statutes

The Second Schaw Statutes were signed on December 28, 1599, at Holyroodhouse. These fourteen rules included specific instructions for Lodge Mother Kilwinning and general rules for all lodges in Scotland. Kilwinning Lodge was given special authority for western Scotland, and its old practices were confirmed.

These statutes also mentioned the "art of memory," which was a technique for remembering things, and was taught by William Fowler, who worked with Schaw.

The statutes also included important safety rules for working at heights. In one rule, Schaw advised: "All masters or undertakers of works be very careful to see their scaffolds and platforms surely set and placed, so that through their carelessness and laziness, no harm or injury comes to persons who work at the said work, under the pain of being forbidden thereafter to work as masters having charge of a work." This meant that masters had to make sure their scaffolding was safe, or they could lose their job!

The Sinclair Statutes

Two letters, written in 1600 and 1601, involved several lodges and were signed by Schaw. These are known as the First Sinclair Statutes. They seemed to confirm the role of the lairds of Roslin as supporters of the stonemason craft. This suggests that Schaw's plans for organizing the masons faced some challenges.

Images for kids

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |