Women's suffrage in Georgia (U.S. state) facts for kids

The fight for women's right to vote in Georgia started slowly. The first group, the Georgia Woman Suffrage Association (GWSA), began in 1892. It was founded by Helen Augusta Howard. This group grew over time, focusing on the idea of "taxation without representation." This meant that women who paid taxes should also have a say in the government.

Howard even convinced the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) to hold a big meeting in Atlanta in 1895. This was the first large gathering for women's rights in the Southern United States. Over the years, Georgia women worked hard. They pushed for changes to laws and for political parties to support their right to vote. More groups formed in the 1910s, and the number of women wanting to vote grew. However, a group against women's suffrage also formed.

Women who supported voting rights took part in parades. They also helped with the war effort during World War I. In 1917 and 1919, women in Waycross and Atlanta got the right to vote in local primary elections. In 1919, Georgia was the first state to reject the Nineteenth Amendment. This amendment would give women across the country the right to vote. Even after the Nineteenth Amendment became law, many women in Georgia had to wait longer to vote because of special rules. White women in Georgia could vote statewide by 1922. However, Native American and African-American women faced more challenges and had to wait much longer. Black women were often left out of the main suffrage movement in Georgia. They formed their own groups to fight for their rights. Georgia finally approved the Nineteenth Amendment on February 20, 1970.

Contents

Early Efforts for Women's Vote

The very first group for women's voting rights in Georgia was the Georgia Woman Suffrage Association (GWSA). It was started by Helen Augusta Howard and her family in Columbus, Georgia. By 1892, people from other parts of the state joined, including those from the temperance movement. This movement worked to reduce alcohol use. By 1893, GWSA had members in five different counties.

The group printed "Taxation without representation is tyranny" on their envelopes. This phrase meant that if you pay taxes, you should have a say in how the government is run. GWSA also had support from some men. In 1894, they shared the opinions of important men who supported women's suffrage in a pamphlet. Early on, GWSA focused on making people aware of why women should vote.

Members of GWSA went to the national suffrage meeting in Washington, D.C., in 1894. Howard asked that the next big meeting be held in Georgia.

Atlanta Hosts National Suffrage Meeting

In January 1895, the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) held its yearly meeting outside of Washington, D.C., for the first time. This happened because Helen Augusta Howard worked hard to bring it to Georgia. The meeting took place in Atlanta. It was the first large gathering for women's rights in the South. Howard and her sisters paid for the meeting themselves.

Georgia suffragist Mary Latimer McLendon was one of the speakers. Susan B. Anthony, a very famous leader, was also a main speaker. The meeting had both men and women speaking. It even had music for entertainment. The governor, William Yates Atkinson, and his wife, Susan Atkinson, attended. Newspapers covered the event, and it impressed many women's groups in the South.

After this big meeting, Frances Cater Swift became the president of GWSA for a year. In 1896, McLendon took over as president.

GWSA Continues to Work

GWSA held its next state meeting in November 1899. They decided to talk to the Georgia General Assembly about many issues, not just women's right to vote. These issues included child labor and laws about the age of consent. GWSA's work helped raise its profile. It also gained the support of the State Federation of Labor.

In November 1901, GWSA held another meeting in Atlanta. Carrie Chapman Catt, another important national leader, spoke there. After the 1902 meeting, women in Atlanta protested because they were not allowed to vote. They even gained the support of Mayor Livingston Mims. Suffragists put signs at voting places that said: "Taxpaying women should be allowed to vote in this bond election."

In 1903, Georgia suffragists tried to make more people aware of their cause. They worked at the Woman's Department at the Inter-State Fair in Atlanta. There, they collected names of supporters and gave out information about suffrage.

In 1909, women in Atlanta asked the city government for the right to vote in city elections. Women in Atlanta paid taxes on a lot of property. They showed that they were being taxed without being represented. But the City of Atlanta said no to women voting in city elections. Again, women protested their lack of voting rights on election day.

Continuing Efforts for Suffrage

The number of members in the GWSA grew in the 1910s. When Rebecca Latimer Felton joined the group in 1912, it brought more attention to the suffrage cause in Georgia. Felton became a representative for Georgia at the national suffrage meeting in Philadelphia.

Interest in women's right to vote increased in Georgia in 1913 and 1914. The Atlanta Constitution newspaper started a women's suffrage section in July, led by McLendon. In 1913, lawyer Leonard Grossman formed the Georgia Men's League for Woman Suffrage. The Georgia Young People's Suffrage Association (GYPSA) also started in 1913. Members of GYPSA marched in the Woman's Suffrage Procession in Washington, D.C., on March 3, 1913.

Also in 1913, the Georgia Woman Suffrage League (GWSL) was created in Atlanta. This group mainly attracted women in Atlanta. So, the Equal Suffrage Party of Georgia (ESPG) was formed in 1914. It grew very quickly, from 100 members to about 2,000 by January 1915. Members of ESPG raised money, held parades, and put on plays.

Rallies and Opposition

In 1914, about 275 meetings for women's suffrage were held across Georgia. These took place in cities like Athens, Atlanta, and Macon. In March 1914, a suffrage rally was held in Atlanta. Famous women like Jane Addams spoke there.

Also in 1914, a group against women's suffrage formed in Macon. It was called the Georgia Association Opposed to Women's Suffrage (GAOWS). James Calloway, who was against suffrage, helped GAOWS get publicity in his Macon newspapers. People against suffrage started writing flyers and publicly challenged suffragists to debates.

In June 1914, a representative introduced a bill for equal suffrage in the Georgia House. Another bill was introduced in the Georgia Senate. The first speech for women's suffrage in the House happened on July 6. On July 7, more women spoke about women's suffrage to a committee in the Georgia House. Both supporters and opponents of suffrage were there. About two hundred women watched from the audience. But the bills for suffrage did not pass.

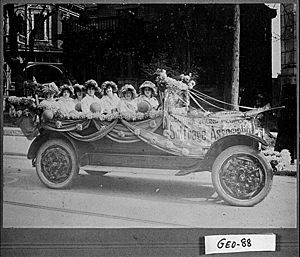

Suffragists held a large parade in 1915 as part of the Harvest Festival Celebration. Eleanor Raoul led the parade on horseback. Behind her, suffragists rode in a car that once belonged to Anna Howard Shaw, another famous suffrage leader. The parade had a marching band and about two hundred marchers, all wearing yellow sashes. After them came female college students in caps and gowns. Then, two hundred decorated cars followed. Even with such a big parade, the police did not help much with traffic.

In February 1916, suffrage groups tried to get 10,000 signatures for women to vote in Atlanta city elections. But they were not successful.

War Efforts and Local Wins

A Georgia branch of the National Woman's Party (NWP) formed in 1917. However, this group was not very popular in Georgia. This was because its national leaders used more aggressive methods to fight for women's suffrage. Beatrice Carleton of the Georgia NWP spoke to the Georgia legislature in July 1917. Rose Ashby from GWSA also spoke. People against suffrage were also there to oppose it, and the bills did not pass. Even though women were not making progress statewide, the city of Waycross, Georgia did allow women to vote in local primary elections.

During World War I, both suffragists and anti-suffragists helped with the war effort. Women in Georgia made clothes for soldiers and raised money for the war and the Red Cross. Suffragists were part of the Women's Council of National Defense. The press in Georgia noticed their work. The Columbus Enquirer Sun praised their efforts.

Rejection, Ratification, and Challenges

Women in Atlanta finally gained the right to vote in city elections in 1919. Mrs. A. G. Helmer, who led the Fulton County Suffrage Association, found that the Atlanta city council supported women's suffrage. On May 3, the city voted to let women vote in city primary elections. Four thousand women registered to vote.

Georgia Rejects the 19th Amendment

On July 1, 1919, the Georgia House and Senate introduced bills to approve the Nineteenth Amendment. This amendment would give women across the country the right to vote. However, Representative J. B. Jackson changed his own bill to say "rejects" the amendment. This meant if the bill passed, it would be a rejection, not an approval.

Suffragists spoke in the House. McLendon questioned why Jackson first supported and then rejected the amendment. Mabel Vernon criticized the rejection. She said it would make the Democratic Party look bad, as they had supported women's suffrage. Other suffragists said it was a bad idea for Georgia to reject women's suffrage. Only Mildred Lewis Rutherford, who was against suffrage, spoke against it.

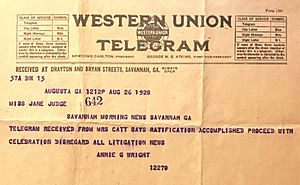

By July 7, members of the House tried to stop Jackson's rejection bill. The bill in the Senate faced the same fate later that month. But eventually, the entire House voted on the bill. Georgia rejected the federal amendment on July 24 by a vote of 118 to 29. Georgia was the first state to reject the amendment. After Georgia rejected it, Eugenia Dorothy Blount Lamar, who was against suffrage, traveled to other states to lobby against the amendment.

Waiting to Vote

Even after the Nineteenth Amendment was approved by enough states and became law, Georgia still did not allow all its women to vote. McLendon and other suffragists tried to vote in the 1920 primary election, but they were not allowed. Georgia had a rule that voters had to register six months before an election. Because of this rule, women could not vote in the 1920 presidential election. McLendon appealed to the Secretary of State, Bainbridge Colby, saying her rights were violated. But he did not help, nor did other state officials.

In March 1920, the Equal Suffrage Party of Georgia closed down. It then formed the Georgia League of Women Voters. In 1921, the Georgia General Assembly passed a law that would allow women to vote and hold public office. White women in Georgia voted statewide in 1922.

However, African-American and Native American women were still kept from voting in Georgia. By 1900, because of a special tax on voters, only about 10 percent of Black men could vote. Black voters had also been stopped from voting in primary elections since 1900.

Georgia finally approved the Nineteenth Amendment on February 20, 1970.

African-Americans and Women's Vote

Many white suffragists in Georgia used ideas about race to help their own cause. Rebecca Latimer Felton supported terrible acts of violence against Black people, even while she strongly supported white women's right to vote. Many white suffragists in Georgia believed that if they got the vote, it would help keep white people in power. They used this idea to promote their cause. Emily C. McDougald wrote to the state government, saying that giving white women the vote would greatly increase white power. She pointed out that there were more white women than Black women in Georgia.

Suffragists like Felton argued that white women needed to vote to protect themselves and to maintain white power. Many white suffragists in Georgia were also upset that Black men got the vote before white women. Mary Latimer McLendon was quoted saying, "The negro men, our former slaves, have been given the right to vote and why should not we Southern women have the same right?" Because of these reasons, most suffrage groups in Georgia did not allow African-American women to join.

However, Black suffragists continued to fight for their right to vote in Georgia. African-Americans had generally supported women's suffrage from the beginning. Black women used churches and groups like the National Association of Colored Women's Clubs (NACW) to organize. Black women were not allowed at the 1895 suffrage meeting. But Susan B. Anthony did go to Atlanta University and speak there. Adella Hunt Logan was one of the people in the audience. Logan joined NAWSA and wrote articles about suffrage for newspapers.

After World War I, brutal violence against Black people increased in the South. A very sad act of violence happened in 1918 to a woman from Valdosta, Georgia, named Mary Turner. Suffragist and NACW leader, Lucy Craft Laney, asked white politicians and women's clubs for help. The help she received was not strong, and it showed Black women in Georgia that they were often on their own. When Black women in Georgia asked for national help with women's suffrage, they were told that their issues involved race, which was outside the main suffrage groups' focus.

The League of Women Voters (LWV) of Georgia did not change its rules until 1956. Until that year, the Georgia LWV's rules said only "white women" could be members. Black women and men in Georgia gained more voting rights after the 1965 passage of the Voting Right Act.

People Against Women's Suffrage

The Georgia Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage started in Macon, Georgia in May 1914. People against suffrage, like Eugenia Dorothy Blount Lamar and Mildred Lewis Rutherford, used the idea of the Lost Cause to argue against women voting. The Lost Cause was a belief that the Southern states fought for a noble cause in the Civil War. Lamar and Rutherford were wealthy women who worked to remember the Confederacy.

Suffragists represented a change to traditional roles for men and women. People against suffrage also said that women voting was an idea from the North. They brought up the Reconstruction era to scare people. Reconstruction was the time after the Civil War when the South was rebuilt. Newspapers in Georgia also showed this view. The Greensboro Herald said it would support women's suffrage only if there were no Black women in the state. Many people against suffrage did not want Black women to ever get the chance to vote. They feared they could not stop them from voting as easily as they did with Black men. They also did not want Black women to use the vote to gain equal rights.

Other Arguments Against Suffrage

Some people against suffrage also believed that women voting would make politics less proper. A preacher in Atlanta said that women voting was against God's laws, using the Bible as his reason. He called men who supported women's suffrage "feeble-minded." Southern Baptists, who had strict ideas about men's and women's roles, were very much against women voting. The LaGrange Graphic worried about how the press might treat women if they got involved in politics.

Many wealthy women felt that voting would upset the traditional system where men held power. They believed it would also ruin women's "moral superiority." Lamar, especially, felt that women did not need to vote. Instead, she thought they should work with the men in their lives to influence politics. Women who supported the traditional system already had a way to influence things. They did not want to lose that power by competing in the same system as men. The Georgia Federation of Women's Clubs (GFWC) never supported women's suffrage. Its president, Mrs. Z. I. Fitzpatrick, felt they were more effective at influencing politics as clubs than individual women would be. She said, "We are the power behind the throne now, and would lose, not gain, by a change."

People against suffrage also did not want working-class women to have more power. They spoke badly about the "quality" of women who worked in factories and other jobs outside the home. After World War I, people against suffrage started claiming that women voting would bring socialism and more labor unions to the country. Others said that women's suffrage would bring atheism to Georgia.