ʻIʻiwi facts for kids

Quick facts for kids ʻIʻiwi |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| An adult ʻIʻiwi in Hawaii | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Fringillidae |

| Subfamily: | Carduelinae |

| Genus: | Drepanis |

| Species: |

D. coccinea

|

| Binomial name | |

| Drepanis coccinea (Forster, 1780)

|

|

|

|

| Where the ʻIʻiwi lives (green) and where it used to live (red) | |

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Vestiaria coccinea |

|

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The ʻiʻiwi (pronounced ee-EE-vee), also known as the scarlet honeycreeper, is a special type of Hawaiian honeycreeper bird. It is a well-known symbol of Hawaiʻi and one of the most common native birds found only in the Hawaiian Islands.

Contents

What's in a Name?

The Hawaiian name ʻiʻiwi comes from an older Polynesian word, *kiwi. This word was used in central Polynesia for a different bird called the bristle-thighed curlew. The curlew has a long, curved beak, much like the ʻiʻiwi's beak.

About the ʻIʻiwi

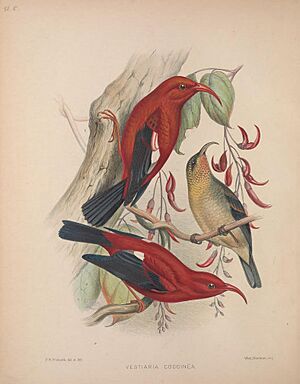

Adult ʻiʻiwi birds are mostly bright red, with black wings and a black tail. They have a long, curved, salmon-colored beak. This beak is perfect for drinking nectar from flowers. Their bright red and black feathers stand out against the green plants, making them easy to spot in Hawaiʻi's forests.

Young ʻiʻiwi birds look different. They have golden feathers with spots and ivory-colored beaks. For a while, people thought they were a different kind of bird! But then, scientists saw the young birds change their feathers as they grew. This showed that they were indeed young ʻiʻiwi.

Long ago, the feathers of the ʻiʻiwi were very important in Hawaii. Hawaiian aliʻi (nobility or chiefs) used these bright feathers to decorate special ʻahuʻula (feather cloaks) and mahiole (feathered helmets). This is why the bird's first scientific name was Vestiaria, which means "clothing" in Latin. The word coccinea means "scarlet-colored," referring to its bright red color.

The ʻiʻiwi is also mentioned in Hawaiian stories and songs. For example, the song "Sweet Lei Mamo" says, "The ʻiʻiwi bird, too, is a friend."

Sounds and Songs

The ʻiʻiwi has a very unique song! It sounds like a mix of whistles, balls dropping into water, balloons rubbing together, and even a squeaky, rusty door hinge.

What They Eat

The ʻiʻiwi's long, curved beak helps it reach the sweet nectar deep inside certain Hawaiian flowers, especially those of the Hawaiian lobelioids. These flowers have curved shapes that fit the bird's beak perfectly.

Around 1902, the number of lobelioid flowers started to drop. So, the ʻiʻiwi began to drink nectar from the flowers of ʻōhiʻa lehua trees instead. ʻIʻiwi also enjoy eating small arthropods, which are like tiny insects.

Life Cycle

In early winter, from January to June, ʻiʻiwi pairs mate when the ʻōhiʻa plants are blooming the most. The female bird builds a small, cup-shaped nest using tree fibers, flower petals, and soft down feathers. She lays two to three bluish eggs.

The eggs hatch in about two weeks. The baby chicks are yellowish-green with brownish-orange spots. They leave the nest after about 24 days and soon grow their adult red feathers.

Where They Live

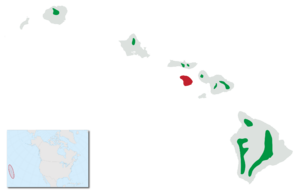

Most ʻiʻiwi live on Hawaiʻi Island. The next largest group is on Maui, especially in East Maui. Very few ʻiʻiwi are left on Kauaʻi. It's possible there are still a few on Molokaʻi and Oʻahu, but they are rarely seen there since the 1990s. They are no longer found on Lānaʻi.

About 90% of all ʻiʻiwi live in a specific forest area. This area is on East Maui and the windy side of Hawaiʻi Island. It's located between 4,265 and 6,234 feet (1,300 and 1,900 meters) high. They prefer forests that are moist to wet and at higher elevations.

These birds are altitudinal migrants. This means they move up and down mountains to follow where flowers are blooming throughout the year. It's also thought that ʻiʻiwi on Mauna Kea, Hawaiʻi Island, might fly down to lower areas every day to find food. When they go to lower elevations for food, they are more likely to get sick from diseases found there. Some people think ʻiʻiwi can even fly between islands. This might be why they haven't disappeared from smaller islands like Molokaʻi.

Dangers and Protection

Even though ʻiʻiwi are still somewhat common, they have lost over 90% of the places they used to live. Because of this, they are now considered a vulnerable species. This means they are at risk of becoming endangered. In 2017, the United States Department of the Interior officially listed them as a threatened species.

Bird Malaria

One big threat to the ʻiʻiwi is Avian malaria. This disease is spread by mosquitoes. Mosquitoes are not native to Hawaii; they were brought there by people. ʻIʻiwi usually live in higher, cooler places where mosquitoes can't survive well. But many native Hawaiian birds, including the ʻiʻiwi, have disappeared from lower elevations because of this disease.

Avian malaria is a main reason why the number of ʻiʻiwi has gone down since 1900. These birds are very sensitive to it. More than 75% of ʻiʻiwi can get sick after just one mosquito bite, and 90% of those sick birds might die.

After breeding season, ʻiʻiwi often fly to lower elevations to find more food from ʻōhiʻa trees. This makes them much more likely to get malaria. Scientists have also found that ʻiʻiwi travel longer distances than other native Hawaiian birds. This might also help spread the disease among them.

With climate change, temperatures are getting warmer, even at higher elevations. This means mosquitoes might be able to live in places where ʻiʻiwi used to be safe. Scientists predict that the ʻiʻiwi could be very close to extinction by the year 2100 if things don't change. There's a plan to try and get rid of mosquitoes in Hawaii completely, since they are not native and don't belong there.

Forest Loss and Tree Sickness

The places where ʻiʻiwi live have shrunk and become broken up. This is because forests have been cleared for farms and grazing animals. Also, plants that are not native to Hawaii can grow quickly and take over, pushing out the native plants that ʻiʻiwi need for food and nesting.

Animals that are not native, like wild pigs, also cause problems. They can trample native plants and spread seeds of non-native plants, making the habitat worse. Wild pigs often create muddy holes called wallows. These holes can fill with rainwater and become perfect places for mosquito larvae to grow, which then spread bird malaria.

Another big problem is the sickness of the ʻōhiʻa tree. These trees are very important because they provide shelter and food for many rare and endangered species, including the ʻiʻiwi. They are a main source of nectar for Hawaiian Honeycreepers. However, many ʻōhiʻa trees are dying from a disease called Rapid ʻŌhiʻa Death. This disease makes the leaves on a branch die very quickly, and then it spreads to the rest of the tree. This tree death means ʻiʻiwi have to go to lower elevations to find food, which puts them at risk of malaria.

Helping the ʻIʻiwi

Scientists are looking into ways to help the ʻiʻiwi fight bird malaria. One idea is to use gene editing to make ʻiʻiwi that are resistant to the disease. However, many of these special birds would need to be released, which would be very expensive.

Other ideas include using gene-edited mosquitoes, controlling wild pigs to reduce mosquito breeding spots, and controlling animals that prey on ʻiʻiwi. Another solution is to remove non-native plants that produce nectar and plant more native flowering plants at higher elevations. This would give the ʻiʻiwi more food in safe, mosquito-free areas.

Groups across the islands have set up nature reserves to protect the native forests. Fences are built to keep out wild animals like pigs, goats, and deer. This allows native plants to grow back and helps restore the birds' homes. These groups are also working hard to stop the spread of Rapid ʻŌhiʻa Death, which could quickly destroy the ʻōhiʻa forests that are so important to the ʻiʻiwi.

See also

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |