1921 British Mount Everest reconnaissance expedition facts for kids

The 1921 British Mount Everest reconnaissance expedition was a journey to explore the areas around Mount Everest. The main goals were to find possible ways to climb the mountain and, if they could, make the first ascent to the top of the world's highest peak.

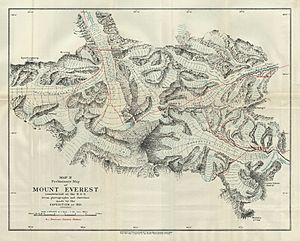

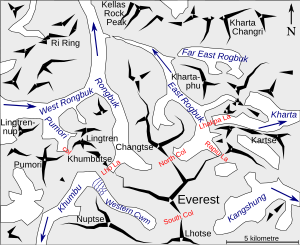

At that time, Nepal was closed to visitors, so the team had to approach Everest from the north, through Tibet. They found a good route from the east, going up the Kharta Glacier and then crossing the Lhakpa La pass, which is northeast of Everest. From there, they had to go down to the East Rongbuk Glacier before climbing up again to Everest's North Col. The expedition reached the North Col, but they couldn't climb any higher before they had to turn back.

Initially, the team explored from the north and found the main Rongbuk Glacier. They thought it didn't offer any good routes to the summit. They didn't realize then that the East Rongbuk glacier actually flowed into the Rongbuk glacier. They thought it went off to the east.

Overall, the expedition was a success. They figured out that a good way to reach the North Col was through the East Rongbuk glacier, which could be accessed via the main Rongbuk glacier. The next year, the 1922 British Mount Everest expedition used this route and managed to climb higher than the North Col, though they still didn't reach the summit.

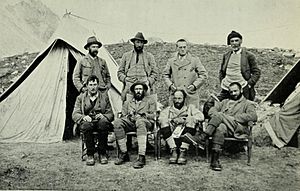

Charles Howard-Bury led the 1921 expedition. George Mallory, who had never been to the Himalaya mountains before, was part of the climbing team. Mallory ended up being the main climber. Howard-Bury later wrote a book about the expedition, and Mallory wrote six chapters for it.

Contents

Why Explore Everest?

In 1856, a mapping project called the Great Trigonometric Survey figured out that the world's highest mountain was not Kangchenjunga, but a peak then known as Peak XV. It was measured to be 29,002 feet high.

By 1907, the Alpine Club planned a British expedition to explore Everest. General Charles Granville Bruce was chosen to lead it. Getting into Tibet, which usually didn't allow foreigners, became possible because of Sir Francis Younghusband's activities, which led to a treaty in 1904.

At first, the British government said no to an expedition for political reasons. This delay, along with World War I, stopped the plans for a while.

By 1920, the government approved the expedition. Colonel Charles Howard-Bury convinced the Viceroy of India (a high-ranking British official) to support the idea. Since Nepal was closed, the team planned to go through Sikkim. The British agent there, Sir Charles Alfred Bell, had a good relationship with the 13th Dalai Lama (Tibet's spiritual leader), who gave the expedition permission to enter Tibet.

In January 1921, the Alpine Club and the Royal Geographical Society (a group that studies geography) formed the Mount Everest Committee. This committee organized and funded the expedition. Even though some members wanted to try for the summit right away, they decided the main goal should be to explore and find routes.

The Expedition Team and Their Journey

General Bruce couldn't lead the expedition because of his military duties, so Howard-Bury became the leader. This was a reconnaissance (exploring) trip, and at the time, no one had been closer than about 60 miles to the mountain.

The expedition started in April 1921. The climbing team included two experienced climbers, Harold Raeburn and Alexander Kellas, and two younger men, George Mallory and Guy Bullock, who had no experience in the Himalayas. The team also had Sandy Wollaston, a naturalist and doctor; Alexander Heron, a geologist; Henry Morshead and Oliver Wheeler, who were army surveyors.

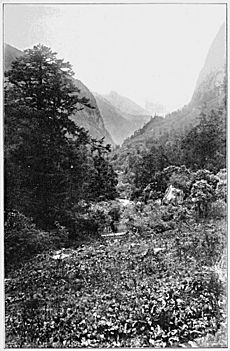

The expedition gathered Sherpas, Bhutias, porters, supplies, and 100 Army mules. They set off from Darjeeling in British India on May 18, 1921, for the 300-mile march to Everest. Along the way, the weather changed from hot and humid with lots of plants and rain, to cold, dry, and very windy.

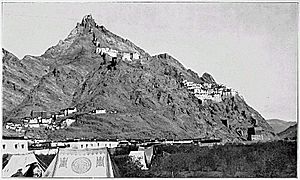

Their route took them through Sikkim, over the Jelep La pass into Tibet, and onto the Tibetan plateau. On June 6, at Khamba Dzong, Kellas suddenly died of heart failure. Raeburn also got sick and had to go back to Sikkim. The team continued west and eventually reached Tingri Dzong, which became their base for exploring the northern side of Everest.

Exploring the Northern Side

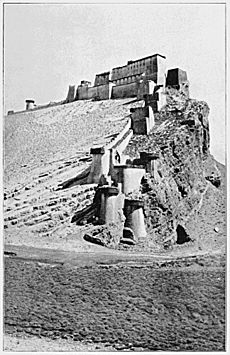

From Tingri, several valleys led south towards Everest. On June 23, Mallory and Bullock, with sixteen Sherpas and porters, headed south. Two days later, at Chobuk, they reached the start of the Rongbuk valley and finally saw Everest. Ten miles further, they found the beginning of the Rongbuk Glacier. They set up base camp at 16,500 feet, near the Rongbuk Monastery.

Mallory and Bullock were used to Alpine glaciers, which are different. They found it hard to get through 50-foot ice towers (seracs) on the Rongbuk Glacier.

Rongbuk Glacier Exploration

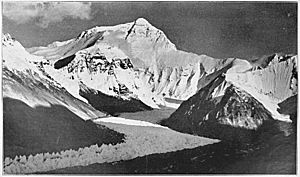

After six days of getting used to the altitude, they set up Camp II at 17,500 feet. On July 1, Mallory and five Sherpas went towards the top of the glacier, near the North Face of Everest. At 19,100 feet, Mallory looked at the western side of the North Col. It seemed there was no good way to reach the North Col from there. However, above the North Col and towards the summit, there seemed to be a possible route. Everest's west ridge didn't look promising from this spot, so Mallory decided to explore the West Rongbuk glacier.

West Rongbuk Glacier Exploration

The area to the west was very complicated. On July 5, Mallory and Bullock climbed the 22,500-foot Ri Ring to get a better view. They looked at the upper North Face and the north ridge above the North Col, thinking the north ridge might be climbable.

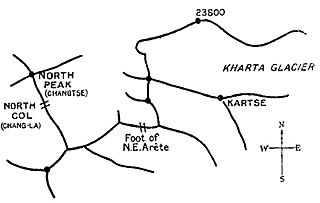

However, they mistakenly thought a high ridge ran from Everest's North Peak all the way east to the Arun river. This made them believe that any approach to the eastern side of the North Col couldn't come from Rongbuk. They didn't realize that the glacier on the other side of the North Col would actually turn back into the main Rongbuk glacier.

Looking more to the west, two routes to Everest seemed promising: one over the Lho La at the head of the Rongbuk glacier, and another over an unnamed pass between Pumori and Lingtren. They hoped a valley south of these passes might lead to the summit. Mallory climbed a peak he called "Island Peak" (Lingtrennup) to take photos of Changtse, Everest, and Lhotse.

By July 19, they reached the unnamed pass by going west up what is now called the Pumori Glacier. From there, they could look down into the Western Cwm and the Khumbu Glacier. They couldn't see the South Col, but the Khumbu glacier looked "terribly steep and broken." The 1,500-foot drop from their pass to the glacier was a "hopeless cliff." This meant any approach through the Western Cwm would have to come from Nepal and would need a different expedition.

On July 20, they packed up their camps, having not found a clear route yet. But the possibility of reaching the North Col from the east remained. Before heading that way, Mallory and Bullock started to investigate the area where, unknown to them, the East Rongbuk glacier flowed out. They had to stop their exploration there because bad news arrived: all the photos Mallory had taken were useless because he had put the photographic plates in backward! Photos were crucial for their exploration, so for two days, Mallory and Bullock rushed to retake as many as possible. On this trip, Mallory retook his photos from "Island Peak," and Bullock actually reached the Lho La and photographed the Khumbu Icefall. On July 25, they rejoined Howard-Bury's group at Chobuk.

Surveying and Other Work

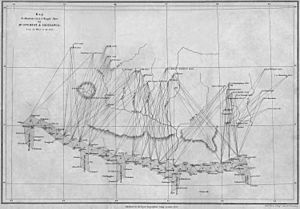

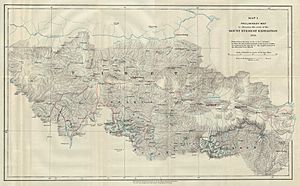

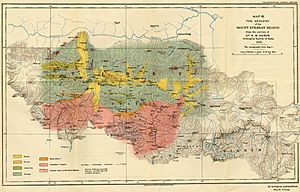

During this time, Morshead and Wheeler had mapped 12,000 square miles of unknown land, creating a map at a scale of four miles to an inch. Wheeler also made a detailed 600-square-mile photographic survey near Everest itself, producing a one-inch map.

Wollaston collected and identified plants, birds, and animals. Heron studied the geology over 8,000 square miles and created a geological map. Reports of these activities were included in Howard-Bury's book.

Howard-Bury had been exploring to the east to find a place for a future base camp. He found the district of Kharta, where a glacial river flowed. Howard-Bury thought it came from Everest, making it a good spot for an eastern base camp if needed. On July 29, the entire expedition moved to Kharta.

Exploring the Eastern Side

Kharta Valley to Kama Valley

Mallory and Bullock suspected the river at Kharta flowed from the North Col, so they headed upstream on August 2. The next day, local people told them a different river flowed from Chomolungma (Everest). So, they crossed an 18,000-foot pass to reach the Kama River valley, which runs parallel but to the south. They were now very close to Makalu, another high peak. Ahead of them to the west, they could see Lhotse and Everest as they approached the Kangshung Glacier and the Kangshung Face.

Mallory wrote about the Kama valley, saying it had "the most magnificent and sublime mountain scenery." However, they believed climbing the Kangshung Face was impossible. Mallory noted, "Other men, less wise, might attempt this way if they would, but, emphatically, it was not for us."

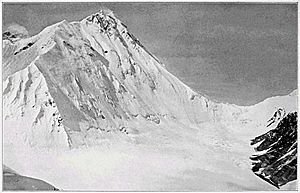

They realized they had to return to the Kharta valley. To do this, they climbed the 21,390-foot Kartse on August 7 to examine the North Col and the Kangshung Face. They wondered if the glacier in the valley to the north was the one from the North Col. Everest's northeast ridge looked very difficult. The North Col and the north ridge above it seemed to be the only remaining possibility. They came down from Kartse to Kama and went back to the Kharta valley.

Return to Kharta Valley

Mallory became ill, so Bullock went west to the head of the Kharta glacier on August 13. Soon, a messenger returned to tell Mallory that Bullock had seen the glacier ended in a high pass ahead. Bullock would explore more, but it looked like the glacier from the North Col did not flow east.

Bullock returned, and Howard-Bury received a letter from Wheeler with his survey results: the glacier flowing down the east side of the North Col turned sharply north and joined the main Rongbuk Glacier. There wasn't enough time to return to Rongbuk, which now seemed the best way to the North Col. So, they decided to explore a route to the pass Bullock had seen, which they named Lhakpa La ("Windy Gap"), to see if the North Col could be reached this way.

The weather was bad, and the glacier was dangerous, but they finally reached the 22,200-foot Lhakpa La on August 18. Mallory decided the route was possible, and so they agreed the exploration could end. They returned to base camp for ten days of rest.

The glacier starting between Everest and the North Peak does not flow east down the "Observed Valley." Instead, it turns north and then west to join the Rongbuk Glacier.

Reaching the North Col

While Mallory and Bullock rested, an advance base camp was set up at 17,300 feet, and Camp II at 20,000 feet on the Kharta glacier. Both camps were left empty. The plan was to have Camp III on the Lhakpa La, Camp IV on the North Col, and one more camp before the summit. However, they greatly underestimated how difficult this would be.

They had to wait a month for the monsoon season to end. On August 31, the whole team, including Raeburn who had unexpectedly returned, moved to the advance base camp.

They stayed at the advance base camp until September 20, waiting for better weather. Then, Mallory, Bullock, Morshead, and Wheeler set off and reached Lhakpa La. They realized that the North Col couldn't be reached without another camp in between. So, they returned to Camp II for more supplies. Then, the whole team (except Raeburn), along with twenty-six Sherpas, set off again for Camp III.

The next morning, Mallory, Bullock, Wheeler, and three Sherpas went down to the East Rongbuk glacier. The rest of the group turned back. After a very difficult night on the glacier in cold and windy conditions, the next day, September 24, the group reached the North Col. They didn't carry heavy loads. The area on the Col was good for a camp, but the wind was extremely strong, making further progress impossible.

They went down to the glacier, where Mallory and Bullock figured out they couldn't set up a camp on the North Col, nor could they survive a bivouac (a temporary shelter) up there at 23,000 feet. Also, the strong winds were getting worse. On September 25, the group was forced to climb back up to the Lhakpa La. On September 26, the entire expedition packed up all the upper camps, returned to Kharta, and eventually reached Darjeeling on October 25 without any problems.

Howard-Bury was given the 1922 Founder's Medal by the Royal Geographical Society for leading the expedition.

What Happened Next

Before the expedition left Tibet, the Mount Everest Committee met. They decided that a full attempt to climb the mountain should be made in 1922, with General Bruce as the leader. They would follow the Rongbuk – East Rongbuk – North Col route. This time, they would bring oxygen tanks for the climbers.

The 1921 expedition was seen as a success by experts and the public. Many people came to the official welcome home event in London. Howard-Bury became a well-known figure. When speaking about the future summit attempt, Mallory said he was "very far from a sanguine estimate of success" (meaning he wasn't very hopeful of success).

Mallory had hoped to stop teaching and become a mountaineer and writer. When he wrote chapters for Howard-Bury's 1922 book, it was understood he would be paid. However, in 1923, three months before leaving for the 1924 Everest expedition, he still hadn't been paid. When he asked the Committee, they changed their agreement and said he wouldn't be paid, but they "fully appreciated the value of your contributions." The 1924 expedition was the one from which he would not return. His body was found in 1999. Bullock's expedition diary was published in 1962.

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |