1924 British Mount Everest expedition facts for kids

The 1924 British Mount Everest expedition was the second time climbers tried to reach the top of Mount Everest. This happened after their first attempt in 1922. During this expedition, Edward Felix Norton set a new world record for climbing altitude, reaching over 8,572 meters (28,123 feet). However, the most famous part of this expedition is the disappearance of two climbers, George Mallory and Andrew "Sandy" Irvine, during their third try for the summit.

People have wondered ever since if Mallory and Irvine actually made it to the top. Mallory's body was found in 1999, but it didn't give clear answers about whether they reached the summit.

Contents

Why They Wanted to Climb Everest

In the early 1900s, British explorers tried to be the first to reach the North and South Poles, but they didn't succeed. To boost their national pride, they decided to try "conquering the third pole"—climbing the world's highest mountain.

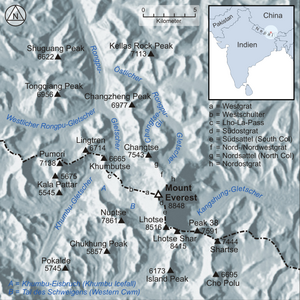

Mount Everest has two main sides for climbing. The south side, in Nepal, was closed to outsiders back then. So, the British had to use the north side, which is in Tibet. Getting permission from the Dalai Lama in Tibet was very difficult and needed help from the British-Indian government.

A big challenge for all expeditions on the north side was the short climbing season. They had to travel a long way from Darjeeling, India, through high mountain passes to Tibet. This journey involved horses, yaks, and many local porters. Climbers usually arrived at Everest in late April and only had about six to eight weeks before the heavy monsoon rains started. This short window was for getting used to the high altitude, setting up camps, and making their summit attempts.

The expedition also had a side mission: to map the area around the Rongbuk Glacier. A surveyor from the Survey of India joined them to help with this task.

Getting Ready for the Climb

Two expeditions came before the 1924 one. The first, in 1921, explored the mountain and found a possible route along the northeast ridge. Later, George Mallory suggested a different path: going to the North Col, then along the north ridge to the northeast ridge, and finally to the summit. This seemed like the easiest way up. After finding a way to the North Col via the East Rongbuk Glacier, this route became the main plan. The 1922 expedition tried this route several times.

There wasn't enough time or money for an expedition in 1923, so the third attempt was postponed until 1924. The Mount Everest Committee, made up of members from the Royal Geographical Society and the Alpine Club, planned and funded the expedition. Captain John Noel also contributed a lot of money, in exchange for all the photo rights.

A key change from earlier expeditions was the role of the porters. The 1922 team realized many porters were excellent climbers. This led to porters becoming more involved, eventually leading to equal partnerships, like Tenzing Norgay and Edmund Hillary's first known ascent in 1953. Over time, the relationship changed from "Sahib-Porter" to "professional-client," where Sherpa porters became the skilled climbing professionals.

Like the 1922 expedition, the 1924 team brought bottled oxygen. The equipment had improved but was still not very reliable. There was also a big debate about whether to use oxygen at all. Some believed climbing Everest should be done "by fair means," without technical help that makes high altitude feel easier. This discussion continues even today.

Who Was on the Team?

General Charles G. Bruce led the expedition again, just like in 1922. He was in charge of equipment, supplies, hiring porters, and choosing the route.

Choosing the climbers was tough, especially because World War I had taken many strong young men. George Mallory returned, along with Howard Somervell, Edward "Teddy" Norton, and Geoffrey Bruce. George Ingle Finch, who had set a height record in 1922, was not included. Some reasons given were that he was divorced and had accepted money for lectures. However, the committee's secretary, Arthur Hinks, also felt it was important for a British climber to be first on Everest, to boost British morale. Mallory initially refused to climb without Finch but changed his mind after the British royal family personally asked him to join.

New climbers included Noel Odell, Bentley Beetham, and John de Vars Hazard. Andrew "Sandy" Irvine, an engineering student, was a new, young addition. He was chosen for his technical skills, which helped improve the oxygen equipment and repair other gear.

Climbers were chosen not just for their climbing skills, but also for their family background, military experience, or university degrees. Military experience was especially important for public image.

The full expedition team included 60 porters and the following members:

| Name | Role | Job |

|---|---|---|

| Charles G. Bruce | Expedition leader | Soldier (Brigadier-General) |

| Edward F. Norton | Deputy leader, climber | Soldier (Lieutenant-Colonel) |

| George Mallory | Climber | Teacher |

| Bentley Beetham | Climber | Teacher |

| Geoffrey Bruce | Climber | Soldier (Captain) |

| John de Vars Hazard | Climber | Engineer |

| R.W.G. Hingston | Expedition doctor | Doctor and Soldier (Major) |

| Andrew Irvine | Climber | Engineering student |

| John B.L. Noel | Photographer, filmmaker | Soldier (Captain) |

| Noel E. Odell | Climber | Geologist |

| E.O. Shebbeare | Transport officer, interpreter | Forester |

| Dr. T. Howard Somervell | Climber | Doctor |

The Journey to Everest

In late February 1924, Charles and Geoffrey Bruce, Norton, and Shebbeare arrived in Darjeeling. There, they chose porters from Tibetans and Sherpas. They hired Karma Paul as a translator and Gyalzen as the leader of the porters. They also bought food and supplies. By the end of March, all expedition members were together, and their journey to Mount Everest began.

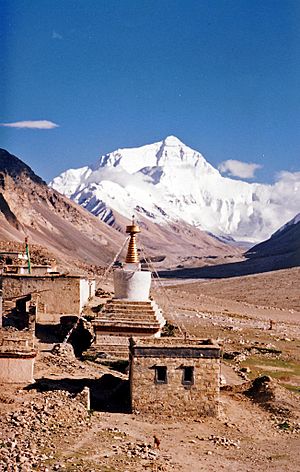

They followed the same route as the 1921 and 1922 expeditions. To avoid overcrowding rest houses, they traveled in two groups. They reached Yatung in early April and Phari Dzong on April 5th. After talking with Tibetan officials, most of the expedition went to Kampa Dzong. However, Charles Bruce and a smaller group took an easier route. During this time, Bruce became very sick with malaria and had to give his leadership role to Norton. On April 23rd, the expedition reached Shekar Dzong. They arrived at the Rongbuk Monastery on April 28th, a few kilometers from their planned base camp. The Lama (spiritual leader) of the monastery was ill and couldn't meet them or perform the traditional Buddhist ceremonies. The next day, the team reached the base camp at the end of the Rongbuk valley. The weather had been good during the journey, but now it turned cold and snowy.

The Climbing Route

Since Nepal was closed to foreigners, British expeditions before World War II could only access the north side of Everest. In 1921, Mallory had spotted a possible route from the North Col to the summit. This route goes up the East Rongbuk Glacier to the North Col. From there, the windy ridges (North Ridge, Northeast Ridge) seemed to offer a practical way to the top.

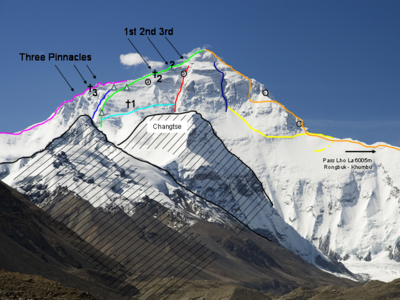

On the Northeast Ridge, there's a huge obstacle called the Second Step at 8,605 meters (28,232 feet). Its difficulty was unknown in 1924. This "step" is a steep rock face about 30 meters (98 feet) high. The hardest part is a 5-meter (16-foot) cliff. Chinese climbers first successfully climbed it in 1960. Since 1975, a ladder has been placed there to help climbers. After this point, the route goes up a steep snow slope to the summit.

The first people to climb this route to the summit were the Chinese in 1960. The British, since 1922, had tried a different path. They would cross the huge north face to the Great Couloir (a steep gully, later called the "Norton Couloir"). Then they would climb along its edge to try and reach the summit. This route wasn't successfully climbed until Reinhold Messner did it alone in 1980. We don't know the exact path Mallory and Irvine took.

Setting Up Camps

The locations for the high camps were planned before the expedition. Camp I (5,400 m / 17,700 ft) was a stop at the entrance of the East Rongbuk Glacier. Camp II (about 6,000 m / 19,700 ft) was another stop, halfway to Camp III (advanced base camp, 6,400 m / 21,000 ft). Camp III was about 1 km (0.6 miles) from the icy slopes leading to the North Col.

About 150 porters carried supplies from base camp to advanced base camp. They were paid about one shilling per day. By the end of April, they had set up these camps, finishing in the first week of May.

Further climbing was delayed by a snowstorm. On May 15th, the expedition members received blessings from the Lama at Rongbuk Monastery. As the weather improved, Norton, Mallory, Somervell, and Odell reached Camp III on May 19th. The next day, they started fixing ropes on the icy slopes to the North Col. They set up Camp IV on May 21st, at a height of 7,000 meters (23,000 feet).

Again, the weather got worse. John de Vars Hazard stayed at Camp IV on the North Col with twelve porters and little food. Hazard eventually managed to climb down, but only eight porters came with him. The other four porters, who had become sick, were rescued by Norton, Mallory, and Somervell. The entire expedition then returned to Camp I. There, fifteen porters who showed the most strength and climbing skill were chosen as "tigers."

Attempts to Reach the Summit

The first summit attempt was planned for Mallory and Bruce. After that, Somervell and Norton would get their chance. Odell and Irvine would support the summit teams from Camp IV on the North Col. Hazard would help from Camp III. The support teams would also be ready for a third try. The first two attempts were made without bottled oxygen.

First Try: Mallory and Bruce

On June 1st, 1924, Mallory and Bruce started their first attempt from the North Col. Nine "tiger" porters supported them. Camp IV was in a somewhat sheltered spot below the North Col. When they left the ice walls, they faced harsh, icy winds. Before they could set up Camp V at 7,681 meters (25,200 feet), four porters dropped their loads and turned back. While Mallory prepared tent platforms, Bruce and one porter retrieved the abandoned loads. The next day, three more porters refused to climb higher. The attempt was stopped without setting up Camp VI as planned. Halfway down to Camp IV, the first summit team met Norton and Somervell, who were just starting their attempt.

Second Try: Norton and Somervell

Norton and Somervell began the second attempt on June 2nd, with six porters. They were surprised to see Mallory and Bruce coming down so early. They wondered if their porters would also refuse to go past Camp V. This fear partly came true when two porters were sent back to Camp IV. But the other four porters and the two English climbers spent the night in Camp V. The next day, three porters carried materials to set up Camp VI at 8,170 meters (26,800 feet) in a small sheltered spot. The porters then returned to Camp IV.

On June 4th, Norton and Somervell started their summit climb at 6:40 AM, later than planned. A spilled water bottle caused the delay. The liter of water each man carried was not enough for their climb, a common problem in pre-WWII expeditions. The weather was perfect. After climbing the North Ridge for over 200 meters (650 feet), they decided to cross the North Face diagonally. However, without extra oxygen, the high altitude forced them to stop often to rest.

Around noon, Somervell couldn't climb higher. Norton continued alone, crossing to the deep gully that leads to the eastern base of the summit pyramid. This gully was named "Norton Couloir." During this solo climb, Somervell took a famous photo showing Norton near his highest point of 8,572.8 meters (28,123 feet). Norton tried to climb over steep, icy ground with some fresh snow. This altitude set a confirmed world climbing record that lasted for 28 years.

The summit was less than 280 meters (920 feet) above Norton when he decided to turn back. The terrain was getting too difficult, he was running out of time, and he doubted his strength. He rejoined Somervell at 2 PM, and they began to descend. Soon after, Somervell accidentally dropped his ice axe, and it fell down the north face.

While following Norton, Somervell had a severe throat blockage. He sat down, thinking he might die. In a desperate last effort, he squeezed his lungs with his arms and suddenly coughed up the blockage, which he described as the lining of his throat. He then followed Norton, who was 30 minutes ahead and didn't know what had happened.

It got dark below Camp V, but they managed to reach Camp IV at 9:30 PM, using "electric torches." Mallory offered them oxygen bottles, showing he was now open to using this help. But their first wish was to drink water. That night, Mallory discussed his plan with Norton: to make a final attempt with Andrew Irvine and use oxygen.

That night, Norton's eyes began to hurt badly. By morning, he was completely snow blind and couldn't see for sixty hours. Norton stayed in Camp IV on June 5th because he knew Nepalese and helped coordinate the porters from his tent. On June 6th, six porters took turns carrying Norton down to Camp III (Advanced Base Camp).

Third Try: Mallory and Irvine

While Somervell and Norton were climbing, Mallory and Bruce had gone down to Camp III (ABC). They then returned to Camp IV (North Col) with oxygen.

On June 5th, Mallory and Irvine were in Camp IV. Mallory talked with Norton about choosing Sandy Irvine as his climbing partner. Norton was the expedition leader after Bruce got sick. Mallory was the chief climber, so Norton didn't challenge Mallory's plan, even though Irvine wasn't very experienced in high-altitude climbing. Irvine was chosen mainly for his skill with the oxygen equipment. Mallory and Irvine had also become good friends on the ship to India. Mallory thought the 22-year-old was "strong as an ox."

On June 6th, Mallory and Irvine left for Camp V at 8:40 AM with eight porters. They carried the improved oxygen gear with two cylinders and a day's food. Their load was about 25 pounds each. Odell took their picture, which was the last close-up photo of them alive. A film from that day shows tiny figures moving up the ridge, but they are over two miles away. That evening, shortly after 5 PM, four porters returned from Camp V with a note from Mallory. It said, "There is no wind here, and things look hopeful."

On June 7th, Odell and Nema, a porter, went to Camp V to support the summit team. On the way, Odell found an oxygen set Irvine had left on the ridge, but it was missing its mouthpiece. Odell carried it to Camp V, hoping to find a spare, but didn't. Soon after Odell arrived, the four remaining porters who had helped Mallory and Irvine returned from Camp VI. The porters gave Odell a message from Mallory:

Dear Odell,---

We're awfully sorry to have left things in such a mess – our Unna Cooker rolled down the slope at the last moment. Be sure of getting back to IV to-morrow in time to evacuate before dark, as I hope to. In the tent I must have left a compass – for the Lord's sake rescue it: we are without. To here on 90 atmospheres for two days – so we'll probably go on two cylinders – but it's a bloody load for climbing. Perfect weather for the job!

Yours ever,

G Mallory

Another message from Mallory carried by the porters said:

Dear Noel,

We'll probably start early to-morrow (8th) to have clear weather. It won't be too early to start looking out for us either crossing the rockband under the pyramid or going up skyline at 8.0 p.m.

Yours ever

G Mallory

(Mallory meant 8 AM, not 8 PM). Mallory used last names, so his letter to Odell started "Dear Odell" (Odell's first name was Noel), while his letter to John Noel started "Dear Noel." Nema became sick, so Odell sent him and the remaining four porters back to Camp IV with a letter for Hazard.

John Noel received the letter and understood the mistake between "p.m." and "a.m." He also knew the location Mallory was talking about, as they had discussed it before. Both the "skyline" and the "rockband" could be seen at the same time through the camera.

On June 8th, John Noel and two porters were at the photographic lookout point above Camp III (Advanced Base Camp) at 8 AM, looking for the climbers. They took turns with a telescope. If anything was seen, Noel would turn on the camera, which was already focused on the agreed spot. They didn't see anyone and could see the summit ridge until 10 AM, when clouds blocked the view.

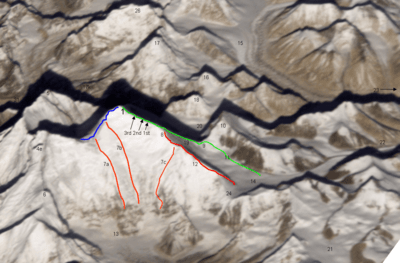

On the morning of June 8th, Odell woke up at 6:00 AM, reporting that the night was calm and he slept well. At 8:00 AM, Odell started climbing to Camp VI to do geological studies and support Mallory and Irvine. The mountain was covered in mist, so he couldn't clearly see the Northeast Ridge where Mallory and Irvine planned to climb. At 7,900 meters (26,000 feet), he climbed over a small rock. At 12:50 PM, the mists suddenly cleared. Odell wrote in his diary, "saw M & I on the ridge, nearing base of final pyramide." In a report to The Times on July 5th, he explained this view. Odell was excited about finding the first fossils on Everest when the weather cleared. He saw the summit ridge and the final pyramid of Everest. His eyes caught a tiny black dot moving on a small snow crest below a rock-step on the ridge. A second black dot was moving towards the first one. The first dot reached the crest of the ridge ("broke skyline"). He wasn't sure if the second dot did too.

Odell first thought the two climbers had reached the base of the Second Step. He was worried because Mallory and Irvine seemed to be five hours behind schedule. After this sighting, Odell continued to Camp VI, where he found the tent in a mess. At 2 PM, a heavy snow squall began. Odell went out, hoping to signal the two climbers, who he thought would be coming down by then. He whistled and shouted, hoping to guide them back to the tent, but gave up because of the intense cold. Odell stayed in Camp VI until the squall ended at 4 PM. He then scanned the mountain for Mallory and Irvine but saw no one.

Because the single Camp VI tent could only sleep two, Mallory had told Odell to leave Camp VI and return to Camp IV on the North Col. Odell left Camp VI at 4:30 PM and arrived at Camp IV at 6:45 PM. Since they hadn't seen any sign of Mallory and Irvine then or the next day, Odell climbed the mountain again with two porters. Around 3:30 PM, they reached Camp V and stayed for the night. The next day, Odell went alone to Camp VI, which was still unchanged. He then climbed to about 8,200 meters (26,900 feet) but found no trace of the two missing climbers. In Camp VI, he laid six blankets in a cross on the snow. This was the signal for "No trace can be found, Given up hope, Awaiting orders" to the advanced base camp. Odell climbed down to Camp IV. On the morning of June 11th, they started to leave the mountain, climbing down the icy slopes of the North Col to end the expedition. Five days later, they said goodbye to the Lama at Rongbuk Monastery.

After the Expedition

The expedition members built a memorial cairn (a pile of stones) to honor the men who had died on Mount Everest in the 1920s. Mallory and Irvine became national heroes. Magdalene College at the University of Cambridge, where Mallory studied, placed a memorial stone in a court renamed for him. The University of Oxford, where Irvine studied, also put up a memorial stone for him. A ceremony was held at St Paul's Cathedral, attended by King George V and other important people, as well as the climbers' families and friends.

The official film of the expedition, The Epic of Everest, made by John Noel, caused a problem later called the Affair of the Dancing Lamas. A group of monks was secretly brought from Tibet to perform a song and dance before each showing of the film. This greatly upset the Tibetan authorities. Because of this and other unauthorized activities during the expedition, the Dalai Lama did not allow further expeditions until 1933.

Odell's Sighting of Mallory and Irvine

Over time, the climbing community began to question where Odell said he saw the two climbers. Many thought the Second Step, if not impossible to climb, was at least not climbable in the five minutes Odell claimed to see one of them go over it. Based on their position, both Odell and Norton believed Mallory and Irvine had reached the summit. Odell shared this belief with newspapers after the expedition. The expedition report was given to Martin Conway, a well-known politician and mountaineer, who also thought the summit had been reached. Conway's opinion was based on their location and Mallory's amazing climbing skill.

Due to pressure from the climbing community, Odell changed his story several times about the exact spot where he saw the two black dots. Most climbers now think he must have seen them on the much easier First Step. In the expedition report, he wrote that the climbers were on the second-to-last step below the summit pyramid, which points to the famous and harder Second Step. Odell's description of the weather also changed. At first, he said he could see the whole ridge and the summit. Later, he said only part of the ridge was clear of mist. After seeing photos from the 1933 expedition, Odell again said he might have seen the climbers at the Second Step. Shortly before he died in 1987, he admitted that since 1924, he had never been sure about the exact location on the northeast ridge where he saw the black dots.

A newer idea suggests the two climbers were just reaching the First Step after giving up their climb and were already on their way down. They might have climbed the small hill to take photos of the rest of the route, similar to what French climbers did in 1981 when they also couldn't go further. Regarding which step they were on, Conrad Anker said it's "hard to say because Odell was looking at it obliquely... you're at altitude, the clouds were coming in." He believes "they were probably near the First Step when they turned back."

What Was Found?

| Green line | Normal route, mainly the Mallory route 1924, with high camps at 7700 and 8300 m. |

| Red line | Great Couloir or Norton Couloir |

| †1 | Mallory found 1999 |

| ? | 2nd step, base at 8605m, height about 30 m, difficulty 5.9 or 5.10 |

| a) | spot at about 8321 m which was George Ingle Finch's highest point with oxygen, 1922 |

| b) | spot at 8,572.8 m at the western edge of the couloir which Edward Felix Norton reached in 1924 without extra oxygen |

Odell found the first clues about Mallory and Irvine's climb among the equipment in Camps V and VI. He found Mallory's compass, which was usually very important for climbing. He also found some oxygen bottles and spare parts. This suggests there might have been a problem with the oxygen equipment, possibly causing a delayed start. A hand-crank electric lamp was also left in the tent. It was still working when another expedition found it nine years later.

During the 1933 British Mount Everest expedition, Percy Wyn-Harris found Irvine's ice axe about 230 meters (250 yards) east of the First Step and 20 meters (60 feet) below the ridge. This location raises more questions. The area is a 30-degree rocky slope with loose stones, according to Wyn-Harris. Expedition leader Hugh Ruttledge said: "It seems likely that the axe marked the scene of a fatal accident. Neither climber would likely leave it there on purpose... its presence suggests it was accidentally dropped during a slip or its owner put it down to use both hands on the rope."

In 1975, during the second Chinese summit climb, Chinese mountaineer Wang Hongbao saw an "English dead" (body) at 8,100 meters (26,575 feet). The Chinese Mountaineering Association officially denied this. However, Wang's report to a Japanese climber, who told Tom Holzel, led to the first Mallory and Irvine Research Expedition in 1986. This expedition was unsuccessful due to bad weather.

In 1999, a new search expedition was launched, led by Eric Simonson and founded by German Everest researcher Jochen Hemmleb. Simonson had seen some very old oxygen bottles near the First Step during his first summit climb in 1991. One of these bottles was found again in 1999 and belonged to Mallory and Irvine. This proved they climbed at least as high as just below the First Step. Their location also suggests a climbing speed of about 84 meters (275 vertical feet) per hour, which is good for that altitude and indicates the oxygen systems were working well. The expedition also tried to recreate Odell's position when he saw Mallory and Irvine. Climber Andy Politz later reported that they could clearly see each of the three steps without any problems.

The most important discovery was the body of George Leigh Mallory at a height of 8,159 meters (26,768 feet). The lack of extreme injuries suggested he hadn't fallen very far. His waist showed severe rope marks, meaning they were roped together when they fell. Mallory's injuries made it impossible for him to walk down: his right foot was almost broken off, and he had a golf ball-sized puncture wound on his forehead. His unbroken leg was on top of the broken one, as if to protect it. A brain surgeon, Dr. Elliot Schwamm, believes he would not have been conscious after the forehead injury. There was no oxygen equipment near the body, but the oxygen bottles would have been empty by then and discarded higher up to reduce weight. Mallory was not wearing snow goggles, although a pair was in his vest, which might mean he was coming back at night. However, a photo from that time shows he had two sets of goggles when he started his summit climb. The picture of his wife Ruth, which he planned to leave on the summit, was not in his vest. He carried the picture throughout the entire expedition, which could mean he reached the top. Since his Kodak pocket camera was not found, there is no proof of a successful climb to the summit.

Did They Reach the Summit?

Since 1924, there have been many claims and rumors that Mallory and Irvine succeeded and were the first to reach the summit of Mount Everest. One argument against this was that their clothing (fleece, vests, trousers) was too poor quality. In 2006, Graham Hoyland climbed to 6,400 meters (21,000 feet) wearing an exact copy of Mallory's original clothing. He said it worked very well and was comfortable.

However, Professor George Havenith, an expert on how the human body handles temperature, tested a precise copy of Mallory's clothing in a weather chamber. His conclusion: "If the wind speed had picked up, which often happens on Everest, the clothing's warmth would only just be enough for -10°C (14°F). Mallory would not have survived any worse conditions."

Odell's sighting is very important. His description and current knowledge suggest that Mallory climbing the Second Step in five minutes is unlikely. This rock face cannot be climbed that fast. Only the First and Third Steps can be climbed quickly. Odell said they were at the base of the summit pyramid, which doesn't fit with being at the First Step. But it's also unlikely they could have started early enough to reach the Third Step by 12:50 PM. Since the First Step is far from the Third Step, confusing them is also not likely. One idea is that Odell mistook birds for climbers, which happened to Eric Shipton in 1933.

This mystery also includes theories about whether Mallory and Irvine could have climbed the Second Step. Òscar Cadiach was the first to climb it without ropes in 1985 and rated it V+ (a very difficult climb). Conrad Anker tried to climb this section without using the "Chinese ladder" (which wasn't there in 1924). In 1999, he couldn't climb it completely freely because he briefly stepped on the ladder when it blocked his only foothold. At that time, he rated the Second Step's difficulty as 5.10, which was beyond Mallory's estimated ability. In June 2007, Anker returned and, with Leo Houlding, successfully free-climbed the Second Step after removing the "Chinese ladder" (which was later put back). Houlding rated the climb at 5.9, which is just within Mallory's estimated capabilities. Theo Fritsche climbed the step alone without ropes in 2001 and rated it V+.

An argument against them reaching the summit is the long distance from high Camp VI to the top. It's usually not possible to reach the summit and return before dark after starting in daylight. It wasn't until 1990 that Ed Viesturs was able to reach the top from a similar distance as Mallory and Irvine planned. Also, Viesturs knew the route, while for Mallory and Irvine, it was completely new territory. Finally, Irvine was not an experienced climber. It's thought unlikely that Mallory would have put his friend in such danger or aimed for the summit without considering the risks.

How and where exactly the two climbers died is still unknown, even though Mallory's body was found in 1999.

Modern climbers who take a very similar route start their summit attempt from a high camp at 8,300 meters (27,200 feet) around midnight. This helps them avoid spending a second night on the descent or a very risky bivouac (sleeping outside without a tent). They also use headlamps in the dark, a technology not available to the early British climbers.

See Also

- 1922 British Mount Everest expedition

- Timeline of Mount Everest expeditions

- List of 20th-century summiters of Mount Everest

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |