2005 Loganair Islander accident facts for kids

Britten Norman Islander in Loganair livery, similar to one involved.

|

|

| Accident summary | |

|---|---|

| Date | 15 March 2005 |

| Summary | Controlled flight into terrain due to fatigue and possible spatial disorientation |

| Place | 7.7 nmi (14.3 km) west-north-west of Campbeltown, Argyll, Scotland 55°29′12″N 5°53′42″W / 55.486666°N 005.895°W |

| Passengers | 1 (paramedic) |

| Crew | 1 (pilot) |

| Fatalities | 2 |

| Survivors | 0 |

| Aircraft type | Pilatus Britten-Norman BN2B-26 Islander |

| Airline/user | Loganair (for Scottish Ambulance Service) |

| Registration | G-BOMG |

| Flew from | Glasgow Airport |

| Flying to | Campbeltown Airport |

On March 15, 2005, a Britten-Norman Islander air ambulance plane, flown by Loganair, crashed into the sea near Scotland. Both people on board, the pilot and a paramedic, sadly died.

The plane was flying to Campbeltown Airport in Argyll, Scotland. It was going to pick up a ten-year-old boy who needed urgent medical help for a suspected appendicitis. The pilot was flying the usual path, which took the plane out over the sea before turning back to the airport. The pilot told air traffic controllers he had made the turn. This was the last message from the plane.

Investigators believe the plane hit the water just seconds after that message. Both the pilot and the paramedic died. The investigation found that the pilot flew the plane too low. It went down into the sea without stopping. The pilot was also very tired and had not flown much recently. He might have been confused or distracted, as he made several mistakes with navigation and his instruments.

The weather was bad, but it was not the main reason for the crash. The boy needing the ambulance was later driven to a hospital in Glasgow. He was treated for a ruptured appendix.

The paramedic's body was found still in his seat. He had a serious head injury from hitting the back of the pilot's seat. Even though both people died, the UK's Air Accidents Investigation Branch (AAIB) thought the crash itself could have been survived by the pilot. If the paramedic had worn a shoulder harness, he likely would have survived the crash with minor injuries. However, he might still have died from the cold water.

The pilot's body was found nine months later. He had been wearing a shoulder harness and likely survived the crash. He probably got out of the plane but then died from hypothermia in the cold water. Because of this accident, new rules were made in 2015 by the European Union (EU). These rules say that all similar-sized planes carrying passengers must have a shoulder harness for every seat.

Investigators also suggested two more changes. These would require two pilots for all air ambulance flights. They would also require a radar altimeter or other warning device for single-pilot flights in bad visibility. These ideas were still being considered by EU regulators at the end of 2015.

Contents

About the Flight Service

Loganair and Ambulance Flights

Loganair started flying air ambulances for the Scottish Ambulance Service (SAS) in 1967. In 2005, they used three special Britten Norman Islander planes, including the one that crashed. These planes helped transport patients from remote places in Scotland. They flew about 2,000 ambulance flights each year.

In February 2005, the SAS announced they would end their contract with Loganair. This was set for October 2006. They planned to use a different company, Gama Aviation, which would provide two planes and two helicopters.

A Similar Accident in 1996

Loganair had another air ambulance accident before this one. It happened on May 19, 1996, and also involved a Britten Norman Islander. In that crash, the pilot died, and two passengers were hurt. At that time, flights often had a nurse and sometimes a doctor. The Islander's cabin was small, so it could be cramped with more people.

The 1996 accident was similar to the 2005 one. It happened at night with a single, tired pilot. He was trying to land in difficult weather. In 1996, strong winds were the main problem, not poor visibility.

After taking a patient to Inverness Airport, the pilot, nurse, and doctor were flying back to their base. There were strong winds at the runway. The pilot had to make right turns to line up with the runway. These turns blocked his view of the runway. When he made his final turn, the plane was too far to the left to land safely.

The pilot tried to land again. But the plane was again blown too far left. It lost a lot of height and hit the ground before reaching the runway. The AAIB found that it was hard to see the airport at night. They suggested that the airport add more lights to help pilots land at night.

The Aircraft and Crew

The Plane: Britten-Norman Islander

The plane was a British-built BN2B-26 Islander. It was made in 1989. It had two engines on its wings. It had fixed landing gear. Loganair bought the plane in 2002 and changed it into an ambulance plane.

Loganair's chief executive, Jim Cameron, said the Islander was "strong" and "good for Scottish weather." Experts also said the plane had a good safety record. It was good at flying from short and rough runways in the Highlands.

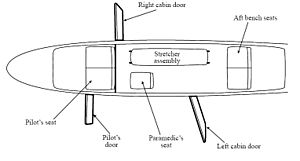

The plane had one stretcher, a paramedic's seat behind the pilot, and two seats in the back. It had two cockpit seats. The plane had an autopilot system. It was approved to be flown by just one pilot.

When the plane was new, it had shoulder harnesses for all eight passenger seats. But when Loganair changed it for ambulance use, they used different seat belts. These new belts were not compatible with the shoulder harnesses. At the time of the accident, shoulder harnesses were not required for passengers.

The plane did not have a Cockpit Voice Recorder (CVR) or a Flight Data Recorder (FDR). It was not required to have them.

The Pilot and Paramedic

The pilot was 40-year-old Guy Henderson. He had flown for 3,553 hours in total, with 205 hours in the Islander. He had not flown for 32 days before the accident because of his schedule and a family trip.

On the day of the accident, Henderson woke up at 6:45 AM. He was supposed to start standby duty from home at 11:00 PM. This meant he had to be ready to fly within an hour. He was called early, at 9:36 PM, and arrived at the airport at 10:20 PM. There was no sign that he tried to sleep during the day.

Loganair required pilots to have flown within the last 28 days to carry passengers. So, when Henderson arrived at Glasgow Airport, he had to fly the plane once to practice. This was called a currency flight. After this flight, he picked up the paramedic. It rained heavily during this practice flight, but nothing else went wrong.

The only passenger was Paramedic John Keith McCreanor, 35. He sat in the paramedic's seat behind the pilot. McCreanor had been a paramedic for twelve years. He arrived for the flight at 11:00 PM but waited for the pilot to finish his practice flight.

The Mission

An officer at Loganair in Glasgow got a call at 9:33 PM. The SAS needed an air ambulance to pick up a ten-year-old boy named Craig McKillop. He had bad stomach pain and suspected appendicitis. He needed to be flown to Glasgow for treatment. The boy's father was supposed to fly with his son and the paramedic. The flight needed to happen within three hours.

The Flight Path

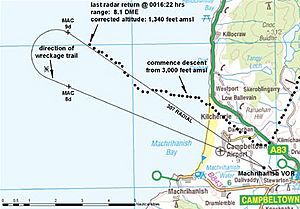

The plane used the callsign LOGAN AMBULANCE ONE. It was cleared by ATC to fly directly to Campbeltown. For unknown reasons, the pilot asked to change the route. He wanted to fly west and then southwest, avoiding the Isle of Arran. This made the flight longer. The plane took off at 11:33 PM. Only one hour was left for the patient transfer.

The plane climbed to its assigned height of 6,000 ft (1,829 m). It then left controlled airspace. The pilot stayed in contact with ATC for information. At 11:59 PM, the controller noticed the plane had not made its planned left turn toward Campbeltown. The controller asked the pilot to confirm his route. He told the pilot he was already west of where he should be. The pilot then made a sharp left turn, then another to the southwest, toward Campbeltown. As the plane flew toward Campbeltown, it had not been on its approved path since leaving Glasgow.

Approach to Campbeltown

When the plane was 6.5 nmi (12.0 km) north of the Machrihanish (MAC) VOR (a radio beacon near Campbeltown Airport), the pilot asked to go down. The controller allowed the plane to go down to 3,900 ft (1,189 m) at 12:03 AM. This was the lowest safe height to be in that area. When the plane was 4 nmi (7 km) from the MAC VOR, it went below this safe height to 3,000 ft (914 m). This height was needed to enter the airport's landing pattern, but not yet. The AAIB called this early descent "unsafe."

The landing procedure for low clouds and poor visibility that night required the pilot to fly over the MAC VOR at 3,900 ft (1,189 m). Then, he had to turn west-northwest over the water, go down to 1,540 ft (469 m), and level off. After that, he would make a left turn back toward the airport. He would then go down for the final landing. The pilot was not allowed to go below 1,540 ft (469 m) until the turn was done. He could not go below 1,045 ft (319 m) unless he could see the runway.

Once the pilot saw the airport from that height, he could circle and land. This is called a circle-to-land manoeuvre. The pilot chose to try this circling approach to land on runway 29. But the clouds at that time would have made it impossible to circle at the minimum height of 1,045 ft (319 m).

As the plane got close to the MAC VOR, the pilot turned right, heading out to sea. This was before reaching the VOR. This made it hard to get the plane on the right path, but he eventually did. The plane started going down on this path. But it did not stop at the minimum height of 1,540 ft (469 m). At 12:16:22 AM, the last radar contact showed the plane 200 ft (61 m) below that height. It was still going down at 1,050 ft (320 m) per minute. At 12:18 AM, the pilot made his last call to the controller. He said he had finished his turn back to the airport. Investigators think the plane hit the water very soon after that call.

Loss of Contact and Search

Five minutes after its last message, the plane had not arrived. The controller tried to contact the pilot many times, but could not. Other controllers asked other planes nearby to try to radio the Islander. They called Loganair and SAS offices, asking them to call the pilot and paramedic on their cell phones. At 12:31 AM, controllers called search and rescue teams.

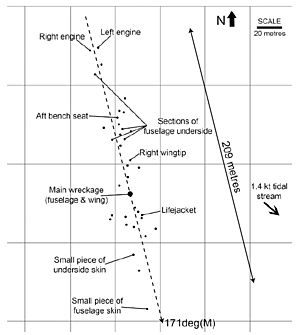

Three lifeboats were sent to the area where the plane was last seen on radar. Two helicopters and a Royal Navy ship also helped. Coastguard teams searched the shoreline. Some parts of the plane were quickly found floating in the water. These included the doors, the paramedic's bag, and a landing gear leg. The main wreckage was under the sea.

The wreckage was 7.7 nmi (14.3 km) west-northwest of Campbeltown airport. The plane's body had broken into three parts. The engines and propellers had broken off. The paramedic's body was found in his seat. The pilot's body was not found near the crash site.

When it was clear the air ambulance would not arrive, the patient was driven to a hospital in Glasgow. He had surgery for a ruptured appendix.

The Investigation

Examining the Wreckage

Floating pieces of the plane were collected soon after the accident. Two days later, officials set up a no-fishing zone near the crash site. The AAIB asked for special equipment to recover the wreckage and the bodies. Six days later, a ship with underwater robots and divers arrived. Within twelve hours, most of the plane's parts were recovered. The wreckage was taken to the AAIB's hangar for study.

All the main parts of the plane were found. The controls were in a neutral position. The flaps were up. Investigators found no sign that the controls were stuck. The landing gear was damaged. Both propellers and engines were recovered. They showed similar damage. Both engines were taken apart and looked at. They seemed to be in good condition.

The cockpit area was not badly damaged. There was enough space for the pilot to survive. The pilot's seat belt and shoulder harness were found unbuckled and undamaged. There was no sign of impact on the controls or the instrument panel. Both fuel tanks had a lot of fuel.

Some instruments were damaged by the crash or by being in the sea. The plane's horizontal situation indicator (HSI), which helps with navigation, was not set correctly. Its course selector was set to 103°, but it should have been 115°. Another part of the HSI, called the "heading bug," was set to 157°. A second navigation instrument was also set incorrectly.

Weather and Pilot Factors

The clouds were low, and visibility was poor at Campbeltown Airport. The wind was from the west. The plane was below the freezing level. It was possible for ice to form in the engines, but there was no sign of engine problems. Some de-icing systems were on, but others were off.

The pilot woke up at 6:45 AM. He was on call overnight, but he did not rest during the day. The AAIB noted that it is hard for a person to sleep during the day. They also said that being awake for 16–17 hours can make a person perform worse. Flying a plane alone in bad weather is a lot of work for a pilot.

During the landing approach, the pilot said he planned to land on Runway 25, even though he knew the actual runway was 29. The AAIB suggested this type of mistake might show the pilot was under a lot of stress. This stress could have made it harder for him to handle the workload. They thought other things like confusion or distraction might have played a part.

Medical Examinations

The pilot's body was found nine months after the accident by a fishing boat. No clear injuries were found. Because of the body's condition, the cause of death could not be determined. The paramedic's body was found still in his seat. He had a major head injury from hitting the pilot's seat. He likely lost consciousness right away. But changes in his lungs showed he died from drowning.

Testing and Conclusions

Investigators tested the paramedic's seat belt. They found that if a person of the same height leaned forward, their head would almost hit the pilot's seat. In a fast stop, or with a loose belt, the head would hit the seat.

Navigation charts warned that the MAC VOR radio beacon was not reliable below 9,000 ft (2,743 m). But a test flight in a similar plane showed it could navigate using the MAC VOR. However, the distance measuring equipment (DME) signal was not received until the plane was 22 nmi (41 km) away.

The AAIB also flew test approaches to Campbeltown Airport. They watched the plane's position on the same radar used on the night of the accident. There was a small gap in radar coverage during the approach. When they flew the test plane at the same height and path as the accident plane, it came very close to the crash site.

Key Findings

The AAIB made 47 findings. Here are some important ones:

- "No technical problem was found that could explain the accident."

- The pilot was allowed to try to land, even though a safe landing was uncertain.

- "A second pilot might have prevented the accident."

- "If the plane had a radio altimeter, or other low height warning device, the accident might not have happened."

- "The pilot was probably suffering from fatigue."

- "The pilot might have been overloaded, which reduced his awareness of the situation."

- "The paramedic probably became unconscious in the crash when his head hit the pilot's seat because he lacked an upper torso restraint (shoulder harness)."

- "Average survival time in the sea, at 9°C, would have been no more than one hour."

Reasons for the Accident

The AAIB found three main reasons for the crash:

- "The pilot allowed the plane to go below the minimum safe height during the landing approach, and this descent likely continued until the plane flew into the sea."

- "Being tired, having too much to do, and not flying much recently likely made the pilot perform worse."

- "The pilot might have been affected by something unknown, like confusion, distraction, or a slight illness. This affected his ability to control the plane's path safely."

Safety Suggestions

The AAIB made three safety suggestions to UK and European regulators: 2006-101: They suggested that all passenger planes under 5,700 kg should be required to have shoulder harnesses for all seats. 2006-102: They suggested reviewing when a second pilot is needed for air ambulance flights, given their special nature. 2006-103: They suggested requiring a radio altimeter (a device that warns of low height) or similar device for single-pilot flights in bad visibility.

What Happened Next

Loganair Changes

After this accident, Loganair put shoulder harnesses and compatible seat belts on one of its two remaining air ambulance planes. This was at the request of the SAS. Loganair's contract with SAS was ending soon anyway. As of January 2016, Loganair still used two Britten-Norman Islanders.

Support for Safety Suggestions

The pilot's fiancée, Lorne Blyth, strongly supported the AAIB's suggestions. She said, "Everything possible should be done to prevent future tragedies." She added, "If a second pilot had been on the aircraft, or if the aircraft had been equipped with a radio altimeter or other low-height warning device, the accident may not have happened." She also asked for personal locator beacons for aircrew. These could help find bodies faster.

Jim McAuslan from the British Airline Pilots' Association (BALPA) agreed. He said, "If there had been a second pilot, he or she would have almost certainly prevented the aircraft's descent into the sea." He added, "We are demanding that air ambulances always have two pilots, not one." He also supported making shoulder harnesses mandatory.

Shoulder Harness Rules

The UK's Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) had already studied the benefits of shoulder harnesses. This was after a 1999 accident. As a result, the CAA changed its rules. It required shoulder harnesses for passengers on certain planes made after February 1, 1989. The CAA also suggested that European regulators adopt a similar rule.

However, at the time of the Loganair accident, Europe had not acted on this suggestion. Even though the UK rule covered the accident plane, Loganair had a special permission from the CAA not to follow it.

Because of this accident, the AAIB again suggested safety rule 2006-101 (about shoulder harnesses) to European regulators. In 2011, the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) agreed. New rules requiring shoulder harnesses for all passenger seats in commercial planes under 5,700 kg became law in Europe.

Requiring Two Pilots and Height Warnings

The other two safety suggestions (2006-102 and 2006-103, about two pilots and height warning devices) were also sent to European regulators. The EASA accepted both suggestions into its plan to make new rules. However, these suggestions were passed from one plan to the next. As of 2016, the EASA expected to make a decision on requiring two pilots for air ambulance flights by 2020. A decision on requiring automatic height-sensing devices was expected by 2019.

|

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |