Aaron Beck facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Aaron Beck

|

|

|---|---|

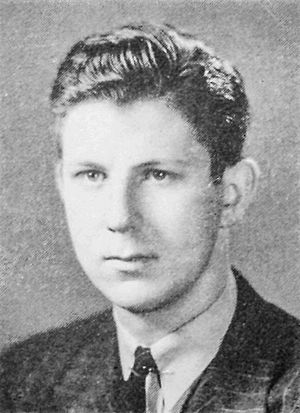

Beck in 1942

|

|

| Born |

Aaron Temkin Beck

July 18, 1921 Providence, Rhode Island, U.S.

|

| Died | November 1, 2021 (aged 100) |

| Alma mater |

|

| Known for | His research on psychotherapy (especially cognitive therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy), psychopathology, and psychometrics |

| Spouse(s) | Phyllis W. Beck (1950-2021) |

| Children | 4, including Judith |

| Awards | See Selected awards and honors |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Psychiatry |

| Institutions |

|

| Influenced |

|

Aaron Temkin Beck (July 18, 1921 – November 1, 2021) was an American psychiatrist. He was a professor at the University of Pennsylvania. He is known as the founder of cognitive therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).

His new methods are used to help people with depression and various anxiety disorders. Beck also created ways to measure how severe depression and anxiety are. One famous tool is the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI). In 1994, he and his daughter, psychologist Judith S. Beck, started the Beck Institute for Cognitive Behavior Therapy. This institute helps people with CBT and trains others.

Beck wrote many articles and books about psychotherapy (talk therapy), psychopathology (mental illness), and psychometrics (measuring mental traits). He was called one of the "most influential psychotherapists of all time." His work at the University of Pennsylvania also inspired Martin Seligman.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Aaron Temkin Beck was born in Providence, Rhode Island on July 18, 1921. He was the youngest of four children. His parents, Elizabeth Temkin and Harry Beck, were Jewish immigrants from Ukraine.

Beck went to Hope Street High School and graduated at the top of his class in 1938. As a teenager, he wanted to be a journalist. He then went to Brown University and graduated with honors in 1942.

Beck attended Yale Medical School, planning to become an internist. He earned his medical degree in 1946. After medical school, he trained in pathology and neurology. He liked the exactness of neurology. However, he was asked to spend six months in psychiatry. He soon became very interested in psychoanalysis, which is a type of talk therapy.

From 1946 to 1950, Beck finished his medical training. He then worked as a fellow in psychiatry at the Austen Riggs Center. This was a mental hospital in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. After this, he served in the United States Armed Forces as assistant chief of neuropsychiatry.

Developing New Ideas

In 1954, Beck joined the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania. He also began formal training in psychoanalysis. Beck started doing research with a colleague, Leon J. Saul. They studied hostility in dreams. Their findings did not match what psychoanalysis predicted.

Beck continued his research. He created the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) in 1961. This tool helps measure how severe a person's depression is. It became very widely used. He also found that depressed patients looked for encouragement, not suffering. This was different from the Freudian theory.

During the 1950s, Beck followed the common psychoanalytic ideas. But he also did his own experiments and had some doubts. In the early 1960s, he faced challenges with the American Psychoanalytic Institute. They questioned his claims of success from shorter therapy. This made him think more about his own methods.

Starting Private Practice

Beck took a break from the university and started his own private practice. In 1962, he began writing notes about thought patterns in depression. He focused on what could be observed and tested. He was influenced by George Kelly's ideas about how people build their own understanding of the world. He was also inspired by Jean Piaget's ideas about schemas, which are mental frameworks.

Beck's first articles on the cognitive theory of depression came out in 1963 and 1964. He started to connect psychiatric ideas with new concepts from cognitive psychology. He also used Socratic questioning in his therapy. This meant helping patients discover things for themselves, rather than just telling them.

In 1967, Beck became more active at the University of Pennsylvania again. He still saw his new therapy as related to earlier ideas. But he focused on how thoughts interact with the environment. His book on depression in 1967 helped introduce cognitive therapy to the world.

Cognitive Therapy Explained

When working with depressed patients, Beck noticed they had many negative thoughts. These thoughts seemed to pop up on their own. He called them "automatic thoughts." He found that these thoughts often fell into three groups: negative ideas about oneself, the world, and the future. He called this the cognitive triad. Patients often believed these thoughts without questioning them.

Beck began to help patients identify and check these thoughts. He found that when patients thought more realistically, they felt better emotionally. They also behaved in healthier ways. He developed key ideas for CBT. He explained that different mental health problems are linked to different types of distorted thinking. This distorted thinking negatively affects a person's behavior.

Beck taught that successful therapy helps people understand their distorted thinking. It also teaches them how to challenge these thoughts. He found that frequent negative automatic thoughts show a person's core beliefs. These core beliefs are formed over a lifetime and feel true to us.

Since then, Beck and his colleagues have studied how well cognitive therapy works. It has been used for many problems. These include depression, bipolar disorder, eating disorders, anxiety disorders, and personality disorders. It has also helped people with schizophrenia. Beck also focused on using cognitive therapy for severe cases of schizophrenia and borderline personality disorder.

His recent research on schizophrenia showed that even patients thought to be untreatable could improve. Even very severe symptoms could respond well to a changed version of cognitive behavioral treatment.

Organizations and Later Life

Beck continued his research at the University of Pennsylvania. He also held regular meetings at the Beck Institute. He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2007.

Beck was the founder and President Emeritus of the non-profit Beck Institute for Cognitive Therapy. He was also the director of the Psychopathology Research Center. He was a visiting scientist at Oxford University in 1986. He became a professor emeritus at Penn in 1992.

Personal Life

Beck married Phyllis W. Beck in 1950. They had four children: Roy, Judy, Dan, and Alice. Phyllis was the first woman judge on an appellate court in Pennsylvania. Their youngest daughter, Alice Beck Dubow, is also a judge on the same court. Their older daughter, Judith, is a well-known CBT expert. She wrote a main textbook in the field and co-founded the Beck Institute. Aaron Beck turned 100 on July 18, 2021. He passed away later that year on November 1 in Philadelphia.

Questionnaires

Besides the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Beck developed other tools. These include the Beck Hopelessness Scale, Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), and Beck Youth Inventories. He also worked with psychologist Maria Kovacs to create the Children's Depression Inventory.

Selected Awards and Honors

- The 7th Annual Heinz Award in the Human Condition

- The 1992 James McKeen Cattell Fellow Award

- The 1999 Joseph Zubin Award

- The 2004 University of Louisville Grawemeyer Award for Psychology

- The 2006 Lasker-DeBakey Clinical Medical Research Award

- The 2010 Bell of Hope Award

- The 2010 Sigmund Freud Award

- The 2010 Scholarship and Research Award

- The 2011 Edward J. Sachar Award

- The 2011 Prince Mahidol Award in Medicine

- The 2013 Kennedy Community Mental Health Award

Beck received special honorary degrees from several universities. These included Yale University, University of Pennsylvania, and Brown University. In 2017, Medscape named Beck the fourth most influential physician of the past century.

Works

Selected books

- Beck, A.T. (1967). The diagnosis and management of depression. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN: 978-0-8122-7674-9

- Beck, A.T. (1972). Depression: Causes and treatment. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN: 978-0-8122-7652-7

- Beck, A.T. (1975). Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. Madison, CT: International Universities Press, Inc. ISBN: 978-0-8236-0990-1

- Beck, A.T., Rush, A.J., Shaw, B.F., & Emery, G. (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression. New York, NY: Guilford Press. ISBN: 978-0-89862-000-9

- Beck, A.T. (1989). Love is never enough: How couples can overcome misunderstandings, resolve conflicts, and solve relationship problems through cognitive therapy. New York, NY: Harper Paperbacks. ISBN: 978-0-06-091604-6

- Scott, J., Williams, J.M., & Beck, A.T. (1989). Cognitive therapy in clinical practice: An illustrative casebook. New York, NY & London, England: Routledge. ISBN: 978-0-415-00518-0

- Alford, B.A., & Beck, A.T. (1998). The integrative power of cognitive therapy. New York, NY: Guilford Press. ISBN: 978-1-57230-396-6

- Beck, A.T. (1999). Prisoners of hate: The cognitive basis of anger, hostility, and violence. New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN: 978-0-06-019377-5

- Clark, D.A., & Beck, A.T. (1999). Scientific foundations of cognitive theory and therapy of depression. New York, NY: Wiley. ISBN: 978-0-471-18970-1

- Newman, C., Leahy, R. L., Beck, A. T., Reilly-Harringon, N. A., Gyulai, L. (2002). Bipolar disorder: A cognitive therapy approach. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. ISBN: 978-1-55798-789-1

- Beck, A.T., Freeman, A., & Davis, D.D. (2003). Cognitive therapy of personality disorders. New York, NY: Guilford Press. ISBN: 978-1-57230-856-5

- Wright, J.H., Thase, M.E., Beck, A.T., & Ludgate, J.W. (2003). Cognitive therapy with inpatients: Developing a cognitive milieu. New York, NY: Guilford Press. ISBN: 978-0-89862-890-6

- Winterowd, C., Beck, A.T., & Gruener, D. (2003). Cognitive therapy with chronic pain patients. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company. ISBN: 978-0-8261-4595-6

- Beck, A.T., Emery, G., & Greenberg, R.L. (2005). Anxiety disorders and phobias: A cognitive perspective. New York, NY: Basic Books. ISBN: 978-0-465-00587-1

- Beck, A.T., Rector, N.A., Stolar, N., & Grant, P. (2008). Schizophrenia: Cognitive theory, research, and therapy. New York, NY: Guilford Press. ISBN: 978-1-60623-018-3

- Beck, A. T. & Alford, B. A. (2009). Depression: Causes and Treatments (2nd ed). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN: 978-0-8122-1964-7

- Clark, D.A., & Beck, A.T. (2010). Cognitive therapy of anxiety disorders: Science and practice. New York, NY: Guilford Press. ISBN: 978-1-60623-434-1

- Creed, T.A., Reisweber, J., & Beck, A.T. (2011). Cognitive therapy for adolescents in school settings. New York: Guildford Press. ISBN: 978-1-60918-133-8

- Clark, D. A., & Beck, A. T. (2012).The anxiety and worry workbook: The cognitive behavioral solution. New York: Guilford Press. ISBN: 978-1-60623-918-6

Selected articles

- Beck, A.T., & Haigh, E. A.-P. (2014). "Advances in Cognitive Theory and Therapy: The Generic Cognitive Model". Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 10, 1–24.

- Beck, A. T., & Bredemeier, K. (2016). "A Unified Model of Depression Integrating Clinical, Cognitive, Biological, and Evolutionary Perspectives". Clinical Psychological Science, 4(4), 596–619.

- Beck, A. T. (2019). "A 60-Year Evolution of Cognitive Theory and Therapy". Perspectives on Psychological Science, 14(1), 16–20.

See also

In Spanish: Aaron T. Beck para niños

In Spanish: Aaron T. Beck para niños

- David D. Burns

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |