Adoptive Couple v. Baby Girl facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Adoptive Couple v. Baby Girl |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Argued April 16, 2013 Decided June 25, 2013 |

|

| Full case name | Adoptive Couple v. Baby Girl, a minor child under the age of fourteen years, Birth Father, and the Cherokee Nation |

| Docket nos. | 12-399 |

| Citations | 570 U.S. 637 (more)

133 S. Ct. 2552; 186 L. Ed. 2d 729; 2013 U.S. LEXIS 4916; 2013 WL 3184627; 81 U.S.L.W. 4590

|

| Prior history | 398 S.C. 625, 731 S.E.2d 550 |

| Argument | Oral argument |

| Opinion Announcement | Opinion announcement |

| Holding | |

| Held that § 1912(f) does not apply to a parent who has never had custody of the child, that § 1912(d) only applies when a relationship between parent and child already exists, and that § 1915(a)'s preferences do not apply when there are no alternative party seeking to adopt the child. | |

| Court membership | |

| Case opinions | |

| Majority | Alito, joined by Roberts, Kennedy, Thomas, and Breyer |

| Concurrence | Thomas |

| Concurrence | Breyer |

| Dissent | Scalia |

| Dissent | Sotomayor, joined by Ginsburg, Kagan; Scalia (in part) |

| Laws applied | |

| 25 U.S.C. §§ 1901–1963 | |

Adoptive Couple v. Baby Girl was a big case decided by the Supreme Court of the United States in 2013. The case was about a young girl and her adoption. It focused on how the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) applies to Native American fathers.

The Court decided that some parts of the ICWA do not apply to Native American fathers who have never had legal care (custody) of their child. This means that special rules for ending a parent's rights might not apply if the child never lived with the father. Also, extra efforts to keep a Native American family together might not be needed. And, placing the child with another Native American family might not be required if no one else has officially tried to adopt the child.

In 2009, a couple from South Carolina, Matthew and Melanie Capobianco, wanted to adopt a child. The child's father, Dusten Brown, was a member of the Cherokee Nation. The mother, Christina Maldonado, was mostly Hispanic. Brown disagreed with the adoption. He said he was not properly told about it, as required by the ICWA. He won in a lower court and then in the South Carolina Supreme Court. In December 2011, the father was given care of the child. This case got a lot of attention in the news.

In October 2012, the Capobiancos asked the U.S. Supreme Court to review the case. The Court agreed in January 2013 and heard the case in April. In June, the Supreme Court made a 5–4 decision. They ruled that a father who did not have custody did not have rights under the ICWA. They sent the case back to the South Carolina courts. In July 2013, the South Carolina court finalized the adoption for the Capobiancos. But in August, the Oklahoma Supreme Court stopped this. The stop was lifted in September 2013. The child was then given to the Capobiancos that same month.

Contents

Understanding the Case: Background

The Indian Child Welfare Act

Before the ICWA was created in 1978, many Native American children were taken from their homes. They were often placed in Native American boarding schools or with non-Native American families. Studies showed that many tribal children were removed from their homes. This also meant they were removed from their tribal culture.

Congress saw that if this continued, the survival of Native American tribes would be in danger. They believed that keeping tribes strong was as important as what was best for the child. They also understood that what was best for a non-Native American child might not be what was best for a Native American child. This was especially true because of the strong role of extended families and tribal connections in Native American cultures.

The Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) was passed in 1978. Its goal was to protect Native American tribes and their children.

The ICWA applies to "Indian children." This means any unmarried person under 18 who is a member of an Indian tribe. Or, they could be eligible for membership and be the biological child of a tribe member.

For adoptions where a Native American parent agrees to give up their child, courts must follow special rules. To give up parental rights, a Native American parent must:

- Do it in writing.

- Do it in front of a judge.

- The judge must confirm the parent understood their actions.

- The parent must understand English or have a translator.

- This agreement cannot be made until at least ten days after the child is born.

A Native American parent can also change their mind about the adoption at any time before it is final. They can even change their mind up to two years after the final order if they were tricked or forced. If parental rights are ended without the parent's agreement, it must be proven "beyond a reasonable doubt." If consent is taken back, or if ICWA rules are not followed, the child must be returned to the Native American parent right away.

Tribal rights are also part of the act. Tribal courts have full authority for cases on Indian reservations. They share authority with state courts elsewhere. A case can be moved from a state court to a tribal court if the tribe asks, unless one of the child's parents objects. The tribe also has the right to join the case to protect the child's tribal rights.

The Case Story

Dusten Brown is a member of the Cherokee Nation. He was serving in the United States Army in Oklahoma. Christina Maldonado was not Native American and was a single mother. Brown and Maldonado were going to get married in December 2008. Maldonado told Brown she was pregnant in January 2009. Brown wanted to marry her and said he would not help financially until they were married.

In May 2009, Maldonado ended their engagement by text message. She stopped talking to Brown. In June, she texted him asking if he would rather pay child support or give up his parental rights. Brown texted back that he gave up his rights. At this time, there was no official order for child support. In general, parents cannot give up their rights just by text message. A court hearing is usually needed to decide what is best for the child.

Before the baby was born, Maldonado worked with an adoption lawyer. She wanted to place the child with Matthew and Melanie Capobianco from South Carolina. The Capobiancos helped Maldonado financially during her pregnancy. They were at the baby's birth in Oklahoma. The adoptive father even cut the umbilical cord.

Oklahoma law says that if a Native American child is to be adopted, the tribe must be told. But Maldonado's lawyer misspelled Brown's name and gave a wrong birth date. So, the Cherokee Nation was not told about the adoption plan. The Capobiancos then took the child to South Carolina.

Four months after the baby was born, and just before he went to Iraq with the Army, Brown was told about the adoption. Brown signed a paper, thinking he was giving up his rights to Maldonado. When he realized what he had signed, he tried to get the paper back. When that failed, he asked for help from the Army's legal office. Seven days after being told about the adoption, Brown stopped the adoption process for a short time because he was in the military. He then went to Iraq.

Trial Court Decision

The adoption case was heard in a family court in South Carolina in September 2011. Brown fought the adoption. The Cherokee Nation also joined the case to protect its rights. The court said no to the Capobiancos' request to adopt the child. It ordered that the child be returned to Brown, the biological father.

The court said that the ICWA was more important than South Carolina state law. It ruled that:

- The ICWA applied to the case and was legal.

- Brown did not agree to end his parental rights or the adoption.

- The Capobiancos did not show enough proof that Brown's parental rights should be ended.

On December 31, 2011, the Capobiancos gave the child to Brown, as the court ordered. The Capobiancos then appealed to the South Carolina Supreme Court.

State Supreme Court Decision

The Supreme Court of South Carolina made its decision on July 26, 2012. The court was split 3–2. The main opinion was given by Chief Justice Jean H. Toal.

The court looked at three main questions: 1. Did the Capobiancos improperly take the child from Oklahoma? 2. Which law decided Brown's status as a parent: state law or the ICWA? 3. Did the Capobiancos prove they should end Brown's parental rights?

The court said that the Capobiancos were wrong about the legal issue of taking the child from Oklahoma. If Oklahoma had been properly told that this was a Native American child, the Cherokee Nation would have been alerted. This would have protected the child's rights as a tribe member.

The Capobiancos argued that just being a biological father was not enough to use the ICWA. They said that under South Carolina law, a father must live with the mother and help with pregnancy costs to have parental rights. However, the court decided that the ICWA does not give way to state law. It ruled that the ICWA gives Native American fathers more rights than state law.

The court then looked at ending Brown's parental rights. The Capobiancos could not show that Brown had agreed to the adoption. The court noted that the ICWA has clear rules, and the Capobiancos did not follow them. The Capobiancos also failed to show that Brown's parental rights should be ended. The ICWA requires that efforts be made to keep the Native American family together. The court noted that the Capobiancos made no such efforts.

The court also talked about what was in the "best interests of the child." They said that for a Native American child, this also means protecting their connection to the tribe. The court stated that it was best for the child to be with her father. This also kept her tribal connection.

Finally, the court looked at the ICWA's rules for placing children. These rules give preference to: 1) another family member, 2) another tribe member, and 3) another Native American family. The court said that the Capobiancos did not plan to follow these rules.

The court agreed with the lower court's decision to return the child to her father. It repeated that the ICWA is more important than state law when ending parental rights for Native American parents.

Dissenting Opinion

Two justices disagreed with the majority. Justice John W. Kittredge wrote the dissenting opinion. He argued that state laws about the "best interest of the child" should be more important than the ICWA in this case. He believed the trial court made mistakes.

He noted that Brown had a low income and had not paid for pregnancy expenses. He also said that the mother had told the adoption agency about the child's Cherokee heritage. But the tribe was not given the correct information about the father.

Justice Kittredge said that even though the ICWA applied, Congress did not mean for it to replace state law regarding a child's best interests. He felt that Brown had "abandoned" his child. He believed Brown should not be allowed to stop the adoption. He also noted that the Capobiancos gave the child a loving and stable home. He would have ruled that ending Brown's parental rights was in the child's best interest.

The Supreme Court's Decision

Arguments Heard

After the South Carolina Supreme Court refused to hear the case again, the Capobiancos asked the Supreme Court of the United States to review it. Many groups sent letters to the Supreme Court, asking them to hear the case. These groups included lawyers and organizations focused on adoption.

On January 4, 2013, the Supreme Court agreed to hear the case. This was only the second time the U.S. Supreme Court had reviewed a case involving the ICWA. The Court heard arguments on April 16, 2013. Lawyers for the Capobiancos, Dusten Brown, and the Cherokee Nation presented their cases.

The main questions for the Court were: 1. Can a parent who does not have custody use the ICWA to stop an adoption that the non-Native American parent started legally? 2. Does the ICWA define "parent" to include an unmarried biological father who has not followed state laws to become a legal parent?

The Court's Main Opinion

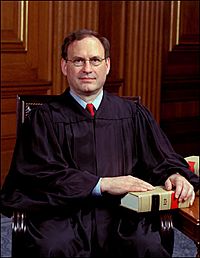

On June 25, 2013, the Supreme Court reversed the lower court's decision. Justice Samuel Alito wrote the main opinion for the five justices who agreed. Alito started by noting that Baby Girl was considered Native American because she was a small part Cherokee.

Alito disagreed with how the lower courts understood the ICWA. He said their reading would make it harder for Native American children to find a loving home. He pointed out that under South Carolina law, Brown would not have been able to object to the adoption.

Alito said that the special rules in the ICWA for ending parental rights do not apply when the parent has never had care of the child. He focused on the words "continued custody" in the law. He also said that the ICWA does not require special efforts to keep a family together if the parent never had custody. Since Brown never had physical or legal care of the child, no special efforts were needed.

Finally, Alito said that the ICWA's preference for placing children with Native American families does not stop a non-Native American couple from adopting if no preferred Native American individuals or groups have officially tried to adopt the child. Alito concluded that allowing Brown to use the ICWA at the last minute would go against the mother's decision and what was best for the child.

Other Opinions

Justice Thomas's Opinion

Justice Clarence Thomas agreed with the main decision. He believed that if the ICWA were applied differently, it might be against the U.S. Constitution. He felt the Court's decision avoided this problem.

Justice Breyer's Opinion

Justice Stephen Breyer also agreed with the main decision. He said that the ICWA does not clearly say how to treat fathers who are not present. He also noted that tribes could change the preferred placement order if they wanted to.

Dissenting Opinions

Justice Scalia's Dissent

Justice Antonin Scalia wrote a short dissenting opinion. He mostly agreed with Justice Sotomayor's dissent. He also said that the phrase "continued custody" could mean custody in the future. This would mean the ICWA rules should still apply even if the father never had custody before. He also felt that biological parents have legal rights that should not be weakened.

Justice Sotomayor's Dissent

Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote a dissenting opinion, joined by three other justices. She felt that the majority seemed to think the Native American placement preference was "unwise." But she argued that this should not allow the Court to change the law's meaning.

Sotomayor said the majority ignored the ICWA's structure. She believed that "continued custody" in the law refers to the ongoing parent-child relationship. She also argued that even a non-custodial father-child relationship is a "family." Therefore, efforts should have been made to prevent it from breaking up. She felt the majority turned the law "upside down."

She also said that the Court's past decisions have always held that being a member of a Native American tribe is not an unfair racial classification. She criticized the majority for repeatedly mentioning the child's small amount of Native American ancestry. Finally, Sotomayor said the majority ignored the main goal of the ICWA. She noted that nothing in the opinion forced the child to be returned to the Capobiancos.

What Happened Next

News Coverage

The case got a lot of attention in the news. Local and national news outlets covered it. Some news reports were criticized for showing the Capobiancos in a good light and Dusten Brown in a bad light.

Terry Cross of the National Indian Child Welfare Association (NICWA) said that despite the negative press, the ICWA was still needed. It helps protect Native American children from losing their tribal rights. He noted that the problems in this case happened because the ICWA rules were not followed.

Legal Events After the Decision

After the Supreme Court's decision, the Capobiancos legally adopted the child on July 31, 2013. At the same time, a group called the Native American Rights Fund filed a lawsuit for the child. They said her rights were violated by the South Carolina court.

An order from a South Carolina court cannot be enforced in Oklahoma without an Oklahoma court agreeing. Brown said he would fight the order in Oklahoma with help from the Cherokee Nation. The Cherokee Nation District Court gave temporary care of the child to Brown's wife and parents while Brown was away for military training.

On August 30, 2013, the Oklahoma Supreme Court stopped an order that the child be immediately moved from Brown's care to the Capobiancos. The Capobiancos had court-ordered visits with the girl in Oklahoma. A mediation meeting between the Browns and the Capobiancos happened in September but did not solve the issue.

The Oklahoma Supreme Court lifted its stop order on September 23, 2013. This allowed the child to be returned to the Capobiancos. The girl was given to her adoptive parents that evening. On September 25, 2013, the South Carolina court started legal action against Brown and the Cherokee Nation. They were accused of not following the South Carolina adoption order.

In October 2013, Brown announced he was stopping his appeals. He said he wanted his daughter to have a chance at a normal life.

In November 2013, the Capobiancos filed a lawsuit in Oklahoma. They asked for over $1 million to cover their court costs during the custody battle. This lawsuit was against Dusten Brown and the Cherokee Nation. The Cherokee Nation said it was not responsible for paying these fees. They said they had special protection from lawsuits without their permission. They also expressed their unhappiness with the Capobiancos' public media appearances during a time when all parties were supposed to keep quiet about the case.

See Also

- Indian Child Welfare Act

- Adoption

- Supreme Court of the United States

Images for kids

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |