Aesop's Fables facts for kids

Aesop's Fables is a famous collection of stories. They are credited to Aesop, a storyteller who lived in ancient Greece more than 2,500 years ago. Many of these tales feature talking animals and teach a valuable lesson, known as a "moral."

For a long time, these stories were passed down by word of mouth as part of an oral tradition. They were not written down until about 300 years after Aesop's time. Over the centuries, new stories were added, and the fables have been retold in books, plays, cartoons, and songs all over the world.

Contents

Who Was Aesop?

We don't know much for sure about Aesop. The ancient Greek historian Herodotus wrote that Aesop was a slave who lived in the 5th century BCE. He was known for being a clever storyteller.

However, modern experts believe that Aesop may not have written all the stories himself. Because he was so famous, his name became attached to any good fable. So, "Aesop's Fables" is really a collection of stories from many different sources, gathered over hundreds of years.

What Makes a Story a Fable?

A fable is a special kind of story that teaches a lesson. The philosopher Apollonius of Tyana said that Aesop "made use of humble incidents to teach great truths." This means he used simple stories to explain big ideas about life.

Fables usually have a few key features:

- They are short and easy to understand.

- They often have animal characters that talk and act like people.

- They almost always end with a moral, which is a lesson about how to behave.

Many famous sayings come from Aesop's Fables. For example, the phrase "sour grapes" comes from The Fox and the Grapes. The moral "slow and steady wins the race" comes from The Tortoise and the Hare. Some fables also try to explain why things are the way they are, like Zeus and the Tortoise, which tells how the tortoise got its shell.

The Journey of the Fables Through Time

From Spoken Stories to Books

For hundreds of years, Aesop's Fables were only spoken aloud. Around 300 BCE, a Greek leader named Demetrius of Phalerum was the first to collect them into a book. Sadly, his collection is now lost. Later, writers like Babrius (in Greek) and Phaedrus (in Latin) wrote the fables down as poems, which helped them survive.

During the Middle Ages, these stories were very popular in Europe. They were often copied by hand in Latin, which was the main language for books at that time.

Printing Spreads the Word

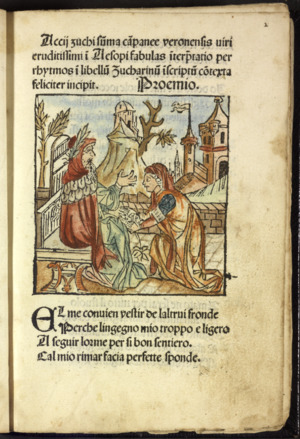

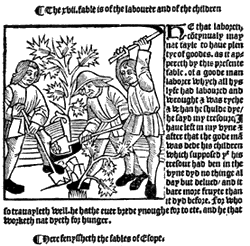

When the printing press was invented in the 1400s, Aesop's Fables was one of the first books to be printed. An edition by Heinrich Steinhöwel in Germany around 1476 was a huge success. It included both Latin and German versions and had many woodcut pictures.

This book was quickly translated into other languages. William Caxton printed the first English version in 1484. Soon, people all over Europe could read the fables in their own language.

Famous Retellings

Some writers became famous for their own versions of the fables. The most celebrated was Jean de La Fontaine from France. In the 1600s, he rewrote the fables as beautiful poems. His versions are so loved in France that many people know them by heart. In Russia, Ivan Krylov also wrote popular versions of the fables in the 1800s.

Fables Just for Kids

For a long time, fables were seen as stories for adults. They were used by teachers and public speakers to make points about serious topics. But in the 1600s, people started to realize that fables were perfect for teaching children.

The philosopher John Locke wrote that fables could "delight and entertain a child... yet afford useful reflection to a grown man." He also said that adding pictures to the books would help children learn and enjoy them even more.

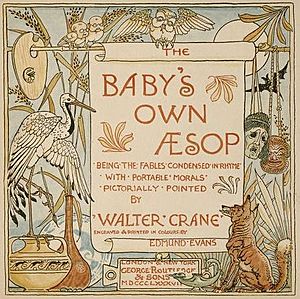

By the 1700s and 1800s, many books of Aesop's Fables were published just for children.

- Reverend Samuel Croxall published a popular version in 1722 with engravings and clear morals.

- Thomas Bewick created beautiful editions with detailed woodcut illustrations.

- Artists like Walter Crane, Arthur Rackham, and Milo Winter created colorful and imaginative pictures that brought the stories to life for new generations.

Fables also appeared on things made for children, like alphabet plates and tiles for the nursery fireplace.

Big Ideas in Fables

Fables are not just simple animal stories. They often explore big questions about life, fairness, and how people should behave.

In ancient times, people used fables to think about justice. For example, one fable asks why bad things sometimes happen to good people. Another story, Hercules and the Wagoner, teaches the lesson that "God helps those who help themselves," meaning you have to make an effort instead of just waiting for help.

As the fables spread to different cultures, people found new meanings in them. A story that was once about a greedy king could be retold to teach a lesson about faith or kindness. This shows how flexible fables are. Their simple plots can be adapted to teach different values, which is one reason they have remained popular for so long.

Fables on Stage and Screen

Aesop's Fables have inspired not just books, but also plays, cartoons, and music.

Plays and Musicals

In the 1690s, a French playwright named Edmé Boursault wrote a popular play called Les Fables d'Esope (Aesop's Fables). It was so successful that it was adapted in England by John Vanbrugh. In modern times, many musicals and plays for children have been based on Aesop's life and stories.

Cartoons and TV

The fables are perfect for animation. In the 1920s, a cartoon series called Aesop's Film Fables was very popular. Walt Disney also created famous cartoons based on the fables, like The Tortoise and the Hare (1935). More recently, the TV show The Rocky and Bullwinkle Show had a segment called Aesop and Son that told funny versions of the classic tales.

Music

Composers have also set the fables to music. Some have written songs for children's choirs, while others have created pieces for orchestras where different instruments represent the animal characters. There has even been a rock opera based on the fables!

A List of Aesop's Fables

Titles A–F

- Aesop and the Ferryman

- The Ant and the Grasshopper

- The Ape and the Dolphin

- The Ape and the Fox

- The Ass and his Masters

- The Ass and the Pig

- The Ass Carrying an Image

- The Ass in the Lion's Skin

- The Astrologer who Fell into a Well

- The Bald Man and the Fly

- The Bear and the Travelers

- The Beaver

- The Belly and the Other Members

- The Bird-catcher and the Blackbird

- The Bird in Borrowed Feathers

- The Boy Who Cried Wolf

- The Bulls and the Lion

- The Cat and the Mice

- The Crab and the Fox

- The Cock and the Jewel

- The Cock, the Dog and the Fox

- The Crow and the Pitcher

- The Crow and the Sheep

- The Crow and the Snake

- The Deer without a Heart

- The Dog and Its Reflection

- The Dog and the Sheep

- The Dog and the Wolf

- The Dogs and the Lion's Skin

- The Dove and the Ant

- The Eagle and the Beetle

- The Eagle and the Fox

- The Eagle Wounded by an Arrow

- Elpis

- The Farmer and his Sons

- The Farmer and the Sea

- The Farmer and the Stork

- The Farmer and the Viper

- The Fir and the Bramble

- The Fisherman and his Flute

- The Fisherman and the Little Fish

- The Fly and the Ant

- The Fly in the Soup

- The Fowler and the Snake

- The Fox and the Crow

- The Fox and the Grapes

- The Fox and the Lion

- The Fox and the Mask

- The Fox and the Sick Lion

- The Fox and the Stork

- The Fox and the Weasel

- The Fox and the Woodman

- The Fox, the Flies and the Hedgehog

- The Frightened Hares

- The Frog and the Fox

- The Frog and the Mouse

- The Frog and the Ox

- The Frogs and the Sun

- The Frogs Who Desired a King

- The Fuller and the Charcoal Burner

Titles G–O

- The Goat and the Vine

- The Goose that Laid the Golden Eggs

- The Hare in flight

- Hercules and the Wagoner

- The Honest Woodcutter

- Horkos, the god of oaths

- The Horse and the Donkey

- The Horse that Lost its Liberty

- The Impertinent Insect

- The Jar of Blessings

- The Kite and the Doves

- The Lion and the Mouse

- The Lion Grown Old

- The Lion in Love

- The Lion's Share

- The Lion, the Bear and the Fox

- The lion, the boar and the vultures

- The Man and the Lion

- The Man with two Mistresses

- The Mischievous Dog

- The Miser and his Gold

- Momus criticizes the creations of the gods

- The Moon and her Mother

- The Mountain in Labour

- The Mouse and the Oyster

- The North Wind and the Sun

- The Oak and the Reed

- The Old Man and Death

- The Old Man and his Sons

- The Old Man and the Ass

- The Old Woman and the Doctor

- The Old Woman and the Wine-jar

- The Oxen and the Creaking Cart

Titles R–Z

- The Rivers and the Sea

- The Rose and the Amaranth

- The Satyr and the Traveller

- The Shipwrecked Man and the Sea

- The Sick Kite

- The Snake and the Crab

- The Snake and the Farmer

- The Snake in the Thorn Bush

- The Stag and the Vine

- The Statue of Hermes

- The Swan and the Goose

- The Tortoise and the Birds

- The Tortoise and the Hare

- The Town Mouse and the Country Mouse

- The Travellers and the Plane Tree

- The Trees and the Bramble

- The Trumpeter Taken Captive

- The Two Pots

- The Walnut Tree

- War and his Bride

- Washing the Ethiopian white

- The Weasel and Aphrodite

- The Wolf and the Crane

- The Wolf and the Lamb

- The Wolf and the Shepherds

- The Woodcutter and the Trees

- The Young Man and the Swallow

- Zeus and the Tortoise

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |