Ahmed Cevdet Pasha facts for kids

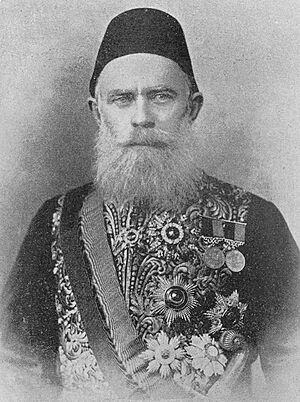

Quick facts for kids Ahmed Cevdet |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Religion | Islam |

| Denomination | Sunni |

| Personal | |

| Nationality | Ottoman Empire |

| Born | 22 March 1822 Lofça, Ottoman Empire |

| Died | 25 May 1895 (aged 73) Constantinople, Ottoman Empire |

| Children | Ali Sedat Fatma Aliye Emine Semiye |

Ahmed Cevdet Pasha (born March 22, 1822 – died May 25, 1895) was an important figure in the Ottoman Empire. He was a smart scholar, a government official, and a historian. He played a big part in the Tanzimat reforms, which were changes made to modernize the Ottoman Empire.

Ahmed Cevdet Pasha led the group that created the Mecelle. This was a special law book that put Islamic law into a clear code for the first time. Many people see him as a leader in creating a civil law system based on European ideas. The Mecelle was used in several Arab countries even in the mid-1900s. Besides Turkish, he knew Arabic, Persian, French, and Bulgarian. He wrote many books about history, law, languages, and more.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Ahmed Cevdet Pasha was born in 1822 in Lofça, which was part of the Ottoman Empire (now in Bulgaria). His family, the Yularkiranoglu, had a history of serving the state and their faith. His grandfather wanted him to work in religious roles. His first name was Ahmed, but his teacher gave him the name "Cevdet" in 1843.

Ahmed started learning at a young age. He first studied Arabic grammar. He quickly learned and soon began studying Islamic sciences. In 1836, he studied with Hacı Esref Efendi, a local judge. Ahmed and the judge's son, also named Ahmed, later became famous as Ahmed Cevdet Pasha and Ahmed Midhat Pasha. His early schooling followed the usual Muslim Ottoman way, learning from local religious scholars.

In 1839, Ahmed moved to Istanbul for more advanced studies. He studied theology, math, geology, and astronomy. He learned Arabic literature and received a special diploma. This diploma allowed him to work in religious positions. He also studied Persian poetry. In 1844, he was allowed to teach the Masnavi, a famous poem. After his teacher died, Ahmed wrote a Turkish explanation for a Persian poetry book.

He also studied math at the Imperial Military Engineering School. He became very interested in history, learning to look at sources carefully. Before he was 30, he also studied Islamic, French, and international law.

Starting His Career

After finishing his studies, Ahmed met Mustafa Reşid Pasha, a very important leader. Mustafa Reşid Pasha was about to become the Grand Vizier (like a prime minister). He needed someone who understood Islamic law to help him make reforms without causing problems. He also wanted someone open-minded. Ahmed Cevdet was chosen to teach Mustafa and his children. He stayed in this role until Mustafa's death in 1858.

Working with these leaders of the Tanzimat reforms introduced Ahmed to new ideas. This led him into government and politics. Even though he kept his ties to religious scholars until 1866, he mostly worked as a government official. He played a key role in improving education, language, and local government.

In 1850–51, Mustafa Reşid made Ahmed the head of a school. This school trained teachers for the new secular (non-religious) school system. Ahmed also became the main writer for the Council on Education. This council created new laws for secular schools. His work as a historian began in 1852. He was asked to write a history of the Ottoman Empire from 1774 to 1826. He also served as the official state historian from 1855 to 1861. In 1856, he became a kadı (judge) in Galata, while still doing his government jobs.

The Tanzimat Period

Working on Reforms

When Mustafa Reşid became Grand Vizier for the sixth time, he made Ahmed a member of the Council of the Tanzimat. This Council was set up to make the reforms into clear laws. Ahmed was very important in writing new laws, especially those about land ownership. His work on the Council also changed how he wrote history. He stopped just listing events and started looking at problems and topics, checking his sources more carefully. Ahmed also wrote the rules for the new Supreme Council of Judicial Ordinances, which he joined in 1861.

Ahmed Cevdet knew that military and government changes were needed. But he was a traditional person and preferred to use Islamic law rather than European law as a model. He had two main ideas. First, he wanted to improve education and communication. Second, he wanted to stop corruption and make the government work better. All this while keeping the basic ideas of the Ottoman Empire. His efforts to mix modern ideas with Islamic law are best seen in his work on the Mecelle.

Other Important Roles

In the 1860s, Ahmed Cevdet officially moved from religious roles to government writing roles.

In 1861, he was sent to Albania to stop revolts and create a new government system. People thought he might become a vizier, but he faced strong opposition from religious scholars. They didn't like his modern ideas about religious matters. So, Mehmed Fuad Pasha became vizier, and Ahmed Cevdet became the inspector general in Bosnia from 1863 to 1864. There, he continued the Tanzimat reforms, even with opposition from other countries. This made him known as someone who could solve problems in the provinces. In 1865, he tried to settle nomadic tribes and bring order to Kozan in southern Anatolia. Finally, in 1866, he officially joined the government administration. He became governor of Aleppo Eyalet, which was set up to apply the new provincial reforms.

Key Contributions

Supreme Council of Judicial Ordinances

In 1868, the Supreme Council was split into two parts: one for making laws and one for judging cases. Ahmed was made the head of the judging part. He then became the first Minister of Justice. He wrote important laws that started a secular (non-religious) court system called Nizamiye courts in the Empire.

Ahmed Cevdet also led a group that disagreed with Mehmed Emin Ali Pasha's idea to use a completely secular, French-style civil law for the courts. He convinced the sultan that the new civil code should be based on Islamic law, but updated for modern times. Ahmed was the head of the group that created this new law code, the Mecelle.

Mecelle

The Mecelle, or Islamic Code, was the new Ottoman civil law book. Ahmed Cevdet Pasha created it for the new secular court system. It was based on traditional Islamic law but also had many important changes. These changes updated the sharia to fit the needs of the time. This code was chosen instead of the French Civil Law that Ali Pasha wanted.

The Mecelle combined civil law with Islamic law in a final book with 1,851 articles. This difficult job took Ahmed Cevdet about 16 years, with the last part published in 1876. It was the first time Islamic law and civil law were put together in such a clear, organized way.

The Mecelle didn't completely stop Western law from influencing Ottoman society. However, it was an important step. It helped create a standard law and changed the Islamic legal system. Making Islamic law into a clear code was important for a modern government to work well. The Mecelle showed that social change was important. It also respected traditional views, like the idea that changes were okay as long as they didn't go against general rules. The articles mainly covered laws about agreements and property rights. But they didn't include laws about people, families, or inheritance. So, the Mecelle wasn't a complete civil law book. Efforts were made in 1914 to fix these gaps, but they couldn't be finished because of World War I.

Later Years and Death

Ministerial Positions

In the last 20 years of his life, Ahmed Cevdet Pasha mostly worked in government jobs, especially in education and justice. In 1873 and 1874, he became Minister of Pious Foundations and Minister of Education. He made big changes to the secular education system. This included improving elementary and middle schools. He also set up new preparatory schools for students wanting to go to higher schools and expanded teacher-training schools.

During this time, some people tried to remove Abdülaziz from power and create a constitution. Ahmed was against this idea. He also disagreed with the government of Mahmud Nedim. Because of this, people who wanted a constitution didn't like him, and he was sent out of Istanbul. The Grand Vizier kept Ahmed busy by making him inspector general in Rumelia and then governor of Syria for a year.

Ahmed Cevdet Pasha was more traditional and had experience in religious law. This made him dislike the reformers who removed Abdülaziz and created the 1876 Ottoman constitution. However, Abdulhamid II became sultan in 1876. He soon started to undo the new First Constitutional Era. He wanted to return to being the sole ruler. He succeeded in 1878, stopping the Ottoman parliament and the constitution. Ahmed Cevdet Pasha was close to Abdulhamid. He served as Minister of Justice in 1876, Minister of the Interior in 1877, Minister of Pious Foundations in 1878, Minister of Commerce in 1879, and Minister of Justice again from 1880 to 1882.

Retirement and Death

Ahmed Cevdet retired from public work for a few years. He wanted to educate his daughters, Fatma Aliye and Emine Semiye. He also wanted to finish his book on Ottoman history, now known as Tarih-i Cevdet ("History of Cevdet Pasha"). He also completed two other historical books, Tezakir ("Memoirs") and Maruzat.

In 1886, he returned as Minister of Justice. But he resigned four years later because of disagreements with the Prime Minister (Grand Vizier) Yusuf Kamil Pasha. After that, Ahmed Cevdet Pasha acted as an elder statesman until his death in Constantinople on May 25, 1895. He is buried in the graveyard of the Fatih Mosque.

Children

Ahmed Cevdet had three children: a son, Ali Sedat (1857–1900), and two daughters. His daughters became important figures in later Ottoman and early Turkish history. One daughter, Fatma Aliye Topuz (1862–1936), is known as the first female writer in Turkish literature. His other daughter, Emine Semiye Önasya (1864–1944), was one of the first Turkish feminists. She was also a political activist for women in the late Empire and early Republic.

See Also

- Turks in Bulgaria

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |